Heavy Culture is a monthly column from journalist Liz Ramanand, focusing on artists of different cultural backgrounds in heavy music as they offer their perspectives on race, society, and more as it intersects with and affects their music. The latest installment of this column features multiple rock and metal musicians recounting their early experiences of racism.

Racism is real. Colorism is real. Implicit biases are real. Injustice is real. It is rooted in ignorance.

As a Caribbean woman, the first time I experienced racism was a vivid memory in the first grade. A white, female classmate, the same age as me — about 6 or 7 years old — told me I was dirty, ugly, and that I did not deserve the new stationery my mom bought for me. Even as a child, I felt that this classmate had disdain for me because I simply existed and did not have lighter skin.

In this installment of “Heavy Culture”, rock and metal artists recount their experiences of racism. Some musicians expressed intense memories of facing bigotry as young children, some as teenagers, and for others, there were too many instances to count.

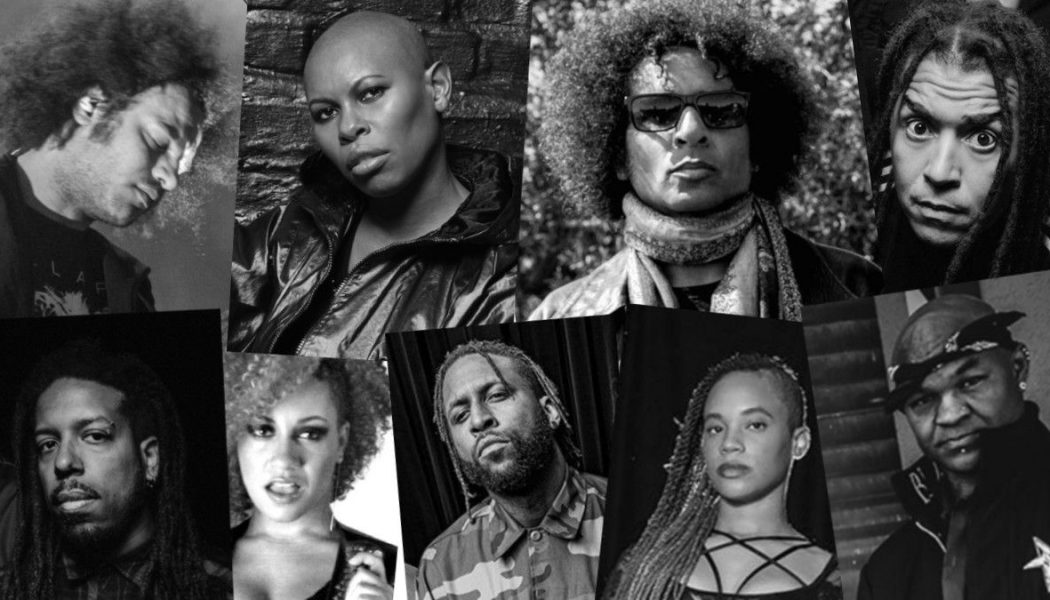

Powerful and painful memories are shared by William DuVall of Alice in Chains; Skin of Skunk Anansie; Manuel Gagneux of Zeal & Ardor; AJ Channer of Fire From the Gods; Militia Vox of Judas Priestess; Rasheed Thomas and Elias Soriano of Nonpoint; Cammie Gilbert of Oceans of Slumber; and Vincent Dennis (aka Vincent Price) of Body Count.

Please read their powerful stories below:

William DuVall, Alice in Chains:

It was in a McDonalds in 1972. I was in kindergarten attending this all-white school in Annandale, Virginia, about 30 miles outside [Washington] D.C. My mother had been an elementary school teacher in the D.C. public school system. She had witnessed firsthand the systemic barriers to getting the mostly-black student population the resources they needed — even basic things like textbooks. She wanted something better for me, so she got me into this private school in Annandale.

My mom was going to law school at the time and when she wasn’t in class, she was working extra jobs to make ends meet. So my grandmother took early retirement from her own job in order to drive me to and from school every day and keep me afterward. It was a long drive every day for a little kid, especially in afternoon rush-hour traffic, so one of my favorite things to do was to stop at this McDonalds near the school to get French fries before the drive home.

One day, I was sitting in a booth waiting for Grandma to come back from the ordering counter with the food. This little kid my age in the next booth over stands up on his bench seat so he can talk to me. He just starts explaining to me that he was better than me because he was white and I was black and that’s just the way it was.

What‘s remarkable to me now looking back is the matter-of-factness of it all. He was just laying down the laws of existence as he saw them — or, more to the point, as his parents saw them because that kid was my age, 5 years old. He was simply parroting what he was being taught at home, carrying on the tradition. The banality of evil. Just like that cop with his knee casually resting on George Floyd’s neck.

That kind of grotesque display of evil starts with a million casual evils before it, like the encounter between me and that other little boy waiting for our French fries. That’s what we live with every day. That’s what we’re fighting. My grandmother was the sweetest, kindest lady that I’ve ever met in my life. I can count on one hand the number of occasions I ever saw her truly get angry. That day in McDonald’s, when she got back from the counter and overheard what that kid was saying to me, was one of those occasions.

Skin, Skunk Anansie:

I grew up in Brixton in South London, which at the time was predominantly black … so I didn’t really experience obvious racism until I was older.

At 15, we were required to have a session with a career’s advice person. I wanted to be a photojournalist. I was already deeply into photography and current affairs. I explained my wishes to the advice tutor who patiently listened, then at the end just shoved an application form for a full-time job at Woolworth’s store. I knew she’d already really helped the white girls in my class, I couldn’t believe it when I got completely different treatment — but it was obvious why.

After that, my eyes were opened and I saw the difference in treatment I received constantly. I decided that I was not the one with the problem; it was not up to me to change my behavior or carry the weight of other people’s issues.

Manuel Gagneux, Zeal & Ardor:

Being mixed, I already was forced to carve my own identity since I didn’t really fit into a group. That being said, seeing my family and friends treated this way and some of my white peers treating it as an annoyance, partially feigning solidarity makes me pick a side these days. I’d love to be able to say that the color of our skin doesn’t matter. Lamentably it does, fatally so.

Growing up in Switzerland as a darker-skinned person, I have a hard time recalling the first time I’ve experienced racism. One time does stand out, though. I must have been 5 or so at the time, and a total stranger elected to scream at my mother and I in a supermarket. We were just paying at the till and this woman yelled that we should go back to where we came from and that we don’t belong here. That was the first time I saw overt hatred on the basis of nothing. I still wonder about that woman.

AJ Channer, Fire from the Gods:

I can’t pick one isolated incident but one [experience] that I have told people a lot was when I was on tour back in 2004 and we got to a club before loading equipment and my drummer and I were walking around town, we were in Seneca, Georgia. We had gone to lunch and had a couple of beers. We went back to the club where the van was parked and the club still wasn’t open.

My drummer and I both had to use a bathroom, we were walking down the street and we find a bar. We walk in and it’s straight out of a Western film, the music stops, everyone looks and they see me, tall with dreads and my drummer and we’re like, “We need to use the bathroom.” The bartender goes, “This is a private club, you [the drummer] can use the bathroom, but your boy can’t.” I remember it vividly.

There are just various times across my life, even when I was young and kids would say, “You can’t do this because you’re a n—er,” I didn’t know what that really meant. I found that very startling and I still remember those things. Many things have happened in my life that it’s hard to pick one experience, but now that I’m older and more receptive, those [memories] really stood out to me.

Militia Vox, Judas Priestess:

My parents were the third interracial couple married in the state of Virginia. My father basically turned his back on his whole family to marry my mother. The first time that I felt and fully understood racism is when I was about 6 years old and my father took me to his sister’s house to visit with her and their mother. My mother did not come with us and she truly didn’t want me going either.

When we were inside the house, I remember some awkward small talk with them. Eventually, I ditched and went exploring around the house. On the mantle, there were pictures of everyone in the family except us — framed photos of all of the kids, except me. The reality sank in. I was kind of embarrassed and wanted to leave. I think my dad thought that if they met me, they’d get to know and love me as he did. It didn’t work out that way.

The other day, one of my cousins from my dad’s side of the family posted on her socials “Black Lives Matter.” She’s the only one on that side of the family to do so. That was f—ing huge, just by making a f—ing Facebook post. Whether she realizes it or not, she virtually ripped off a Band-Aid that’s been covering a deep family wound, finally giving it air to heal.

Rasheed Thomas, Nonpoint:

I grew up in black neighborhoods and went to black schools; I hadn’t really experienced many other races until I was a teenager. I was about 14 or 15 years old and I started going to a summer camp in Wisconsin. I made friends with people of all colors. I started hanging out with some of them outside of the summer camp and I’m still great friends with these people to this day.

One time I went out to visit them in a suburb of the city, me and my homies were taking public transportation to get there and get home. When we were waiting for the bus to go back home, a car drove around the corner with a guy screaming out the window, “Go home n—er,” and proceeded to do this a couple of times.

Now there’s always the softer versions of racism that’s out there like walking past ladies and they clench their purses tighter, but this was blatant. And I was like, “Damn… what year are we in”? This was like 1996! We’ve come a long way from the times of slavery. But unfortunately, it let me know that racism is still here and not going anywhere anytime soon.

Cammie Gilbert, Oceans of Slumber:

The first time I recall experiencing racism was when I was about 12 years old. I was with my best friend at the time, her brother, and their mothers. Her brother had a friend with him as well, another little black boy; the two boys were about 14. My best friend, her brother, and their moms were white.

We were all traveling back to Houston after spending a week at Disney World in Florida. We were driving in the evening, passing through Alabama when a truck drove up beside us. It had a confederate flag waving and two or three white men were yelling and flipping us off. They swerved into our lane, and cut us off, and would get back in front of our van if we tried to go around. We were the only two cars on this dark country road — it lasted for only a couple of minutes, but their snarls and angry faces are burned into my memory.

Having already learned the danger of some confederate flag bearers, and knowing that having two moms made some people mad, I knew they were angry at us for things we hadn’t done to them, but just because we were different from them. I remember my best friend holding my hand, and her moms telling us to lay down on the seats until they went away. Eventually, they drove off and we didn’t stop driving until we reached Louisiana.

Vincent Dennis (aka Vincent Price), Body Count:

I don’t remember the first time I experienced racism, but I do remember at the age of 16 when I was in high school, this white guy called me a n—-er. Most of my friends were white, so I would get teased by blacks for hanging with them. Blacks would call me names like Uncle Tom, Oreo, etc., and this white guy had the nerve to call me a n—er. I had a lot of built-up anger and this guy pushed my last button. He was a lot bigger than me. We fought and I beat him up so bad that he had to get some teeth replaced. I got kicked out of the whole school district of Pomona, so I had to go to school in Los Angeles, which was about two hours away from where I lived.

Another memory I have that stands out in my mind was when I was at a grocery store in Pomona and a black lady approached me. She looked me up and down and said, “You are a disgrace to the black race.” Maybe she didn’t like how I was dressed or something; you know how kids dress today with different hair colors etc. I just wanted to be an individual and do my own thing.

With all that said, I just want it to end here. There is so much hate in the world and I’m just sharing my experience. I am not saying that violence is the way at all; it is just something that I went through at a young age. I’ve always felt racism from both sides. I just hope that things will change for the better for future generations to come.

Elias Soriano, Nonpoint:

(Recent experience with racism in 2020)

Three weeks ago I was walking to the park with my daughter. I’m a Latino with dreadlocks, while my daughter has curly blonde hair and blue eyes. A police officer pulls up like a bat out of hell with his hand on his gun [and] a caucasian woman about 60 years old comes running up with the police officer saying, “That’s him” and then proceeding to look at my daughter and asking her if she’s okay. Upon which the officer asked me for ID and asked if my daughter was actually my daughter.

Now I want you to think for a second. Imagine you’re walking with your child and someone pulls up and demands that you prove that that’s your child, even though your child is laughing and skipping holding your hand on the way to the park. I said, “Of course this is my daughter! And I don’t have to prove shit to you or this lady.” Then the police officer asked my daughter if I was her dad—something my daughter will never forget.

I turned and glared at the woman, who was visually upset that she was wrong and it was actually my daughter and said, “Thank you for creating such a wonderful lasting memory in my daughter’s life.” The police officer got angry at me and told me to just walk to the park. Then proceeded to turn and talk to the lady and say these words, “It’s OK, I understand why you called me.”

I ask anyone reading this, do you understand why he was called? Was it justified? That’s systemic racism in the flesh. That woman weaponized the police against an innocent father and the police consoles the old white lady. Why? Because she was the only white person in the situation. As it seems for most people of color, the police don’t seem to be here to protect us from evil but to protect whites from non-whites. Hence the term ACAB (All Cops Are Bastards) being so popular among the protestors. They all are catching a glimpse of what people like me have dealt with since I turned from a cute 8-year old Spanish boy, into a suspect.

(Early experience with racism in 1978)

Biracial people will really feel what I’m about to say. I’ve received the racism from both sides of the spectrum. I have very fair skin, considered white to non-white people. The only thing that makes it obvious that I’m not is my hair. So I’m not white enough to be white, but I’m not black enough to be black.

My father was born in the Dominican Republic, so he is African and my mother is Puerto Rican. Spanish, British and Dutch slave traders traveled through the Caribbean conquering the indigenous people. As some of those travelers settled in the Caribbean, they merged with the local people along with their slaves and eventually my people were born — dark and light Latinos. I was a light one and my brother was darker. I learned that was a deciding factor when I went to a predominantly African-American school and my brother had to protect me from the anger and frustration of the kids at that school towards Caucasians.

By middle school, I learned the funny guy never gets picked on, so I used comedy as a shield. Once I gained social acceptance (and started wrestling and doing other sports), I would use that shield to protect people in the LGBT community and other Latin kids being targeted at my school. It was scary but I understood why.

Because you see, my earliest memory was at 3 years old, hiding underneath the dashboard of our truck as my mother drove through the South because she didn’t want anyone to see her biracial children in fear of what might happen to her and us. That’s my earliest memory of racism. I was 3. The Civil Rights movement abolished racism with Martin Luther King, right? So why does my mother have to hide me under the dashboard in 1978? I’ll leave you with that to think about.