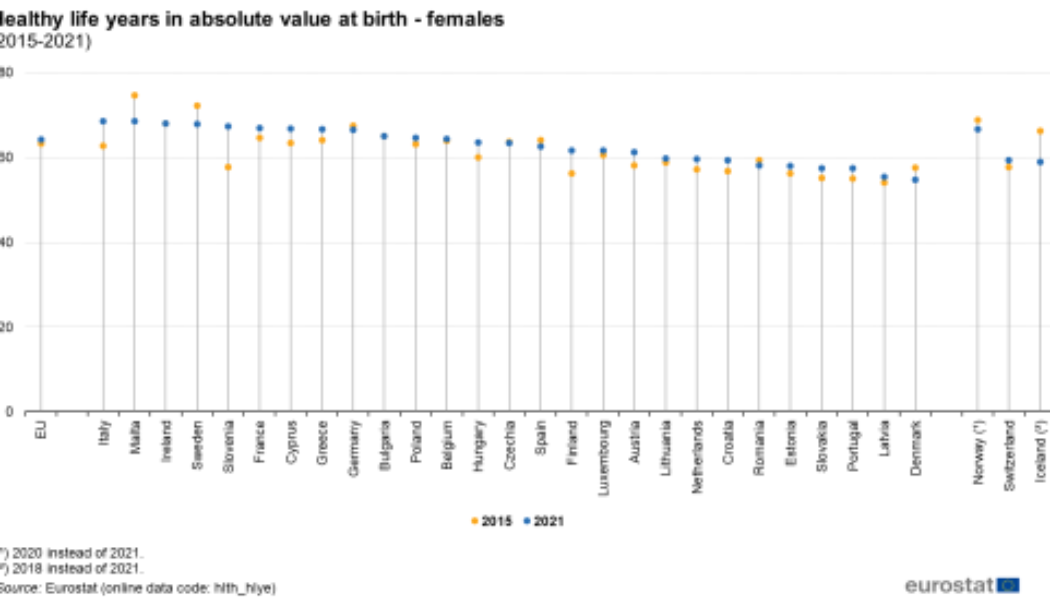

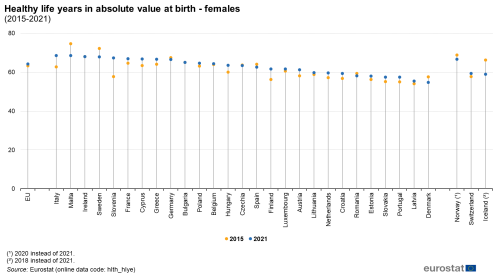

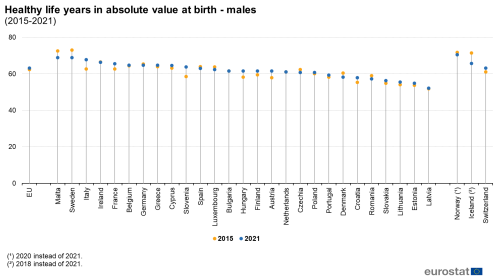

Healthy life years at birth

In 2021, the number of healthy life years at birth was estimated at 64.2 years for women and 63.1 years for men in the EU.

The gender gap was considerably smaller in terms of healthy life years than it was for overall life expectancy.

Life expectancy for women in the EU was, on average, 5.7 years longer than that for men in 2021. However, most of these additional years tend to be lived with activity limitations.

Indeed, at just 1.1 years difference in favour of women, the gender gap was considerably smaller in terms of healthy life years than it was for overall life expectancy. Men, therefore, tend to spend a greater proportion of their somewhat shorter lives free from activity limitations.

Across the EU Member States, life expectancy at birth for women in 2021 ranged between 75.1 years in Bulgaria to 86.2 years in Spain; a difference of 11.1 years. A similar comparison for men shows that the lowest level of life expectancy in 2021 was also recorded in Bulgaria 68.0 years and the highest in Sweden 81.3 years; a range of 13.3 years.

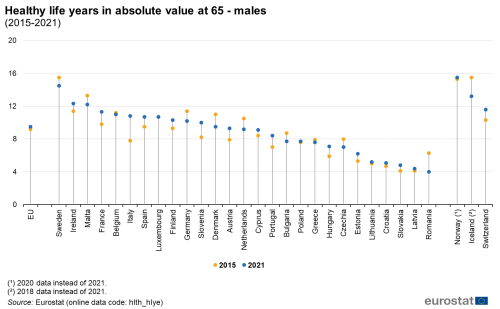

The corresponding range for healthy life years at birth:

- For women (Figure 1) was between 54.8 years in Denmark and 68.5 years in Italy and Malta (a range of 13.7 years),

- While that for men (Figure 2) was between 52.2 years in Latvia and 68.9 years in malta (a range of 16.7 years).

(2015-2021)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_hlye)

(2015-2021)

Source: Eurostat (hlth_hlye)

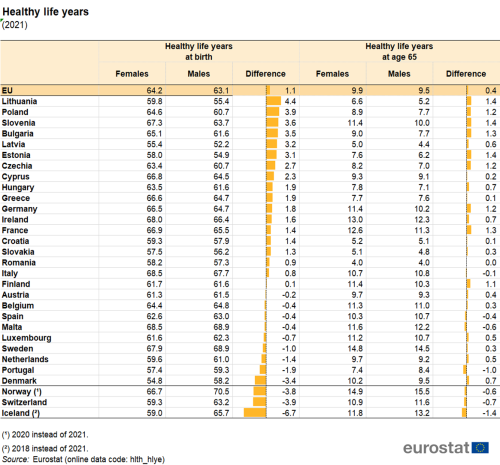

The expected number of healthy life years at birth was higher for women than for men in 18 of the Member States, with the difference between the sexes generally relatively small, as there were only six Member States where the gap rose to more than 3.0 years in favour of women — Lithuania, Poland, Slovenia, Bulgaria, Latvia and Estonia (see the Table 1).

Source: Eurostat (hlth_hlye)

As such, it is clear that there are considerably wider differences between EU Member States in terms of the quality of life (health wise) that their respective populations may expect to live, when compared with the overall differences in life expectancy. In 2021, a woman born in Denmark could expect to live 65.8 % of her life free from any limitation, a share that rose to 86.7 % in Bulgaria. In 2021, a man born in Denmark could expect to live 73.0 % of their lives free from any activity limitation, whereas the share rose to as high as 90.5 % in Bulgaria.

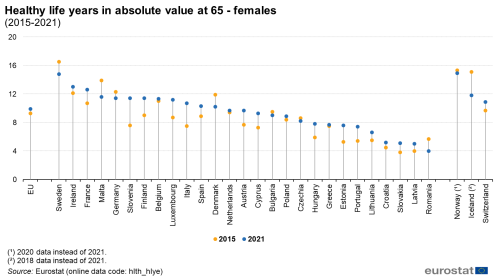

Healthy life years at age 65

An analysis comparing healthy life years between the sexes at the age of 65 in 2021 shows that there were 22 EU Member States where women could expect more healthy life years than men; this was most notably the case in Estonia, Lithuania and Slovenia where women aged 65 could expect to live 1.4 years longer free from disability than men.

By contrast, men could expect to live 1.0 years longer free from disability than women in Portugal, and 0.6 years longer in malta.

Source data for tables and graphs

Data sources

Eurostat calculates information relating to healthy life years for three ages: at birth, at age 50 and at age 65. It is calculated using mortality statistics and data on self-perceived long-standing activity limitations. Mortality data come from Eurostat’s demographic database, while self-perceived long-standing activity limitations data come from a European health module that is integrated within the data collection EU statistics on income and living conditions (EU-SILC).

Self-perceived long-standing limitations in usual activities due to health problems

EU-SILC is documented in more detail in this background article which provides information on the scope of the data, its legal basis, the methodology employed for health-related variables, as well as related concepts and definitions.

The general coverage of EU-SILC is all private households and their members (who are residents at the time of data collection); this therefore excludes people living in collective households.

The relevant EU-SILC questions concerning the long-standing activity limitation are: ‘Are you limited because of a health problem in activities people usually do? Would you say you are … severely limited, limited but not severely or not limited at all?

If the answer is ‘severely limited’ or ‘limited but not severely’ ask: ‘Have you been limited for at least the past 6 months? Yes, No.’

Limitations of the data

The indicator presented in this article is derived from self-reported data so it is, to a certain extent, affected by respondents’ subjective perception as well as by their social and cultural background.

EU-SILC does not cover the institutionalised population, for example, people living in health and social care institutions who are more likely to face limitations than the population living in private households. It is therefore likely that, to some degree, this data source under-estimates the share of the population facing activity limitations. Furthermore, the implementation of EU-SILC was organised nationally, which may impact on the results presented, for example, due to differences in the formulation of questions or changing the related questions in a specific year.

Context

The health status of a population is difficult to measure because it is hard to define among individuals, populations, cultures, or even across time periods. As a result, the demographic measure of life expectancy has often been used as a proxy for the state of a nation’s health, partly because it is based on a characteristic that is simple and easy to understand — namely, that of death. Indeed, life expectancy at birth remains one of the most frequently quoted indicators of health status and economic development and it has risen rapidly in the last century due to a range of factors, including: reductions in infant mortality, rising living standards, improved lifestyles, better education, as well as advances in healthcare and medicine.

While most people are aware that successive generations are living longer, less is known about the health of the EU’s ageing population. Indicators on healthy life years introduce the concept of the quality of life, by focusing on those years that may be enjoyed by individuals free from the limitations of illness or disability. Chronic disease, frailty, mental disorders and physical disability tend to become more prevalent in older age, and may result in a lower quality of life for those who suffer from such conditions, while the burden of these conditions may also impact on healthcare and pension provisions.

Healthy life years also monitor health as a productive or economic factor. An increase in healthy life years is one of the main goals of the EU’s health policy, given that this would not only improve the situation of individuals (as good health and a long life are fundamental objectives of human activity) but would also lead to lower public healthcare expenditure and likely increase the possibility that people continue to work later into life. If healthy life years increase more rapidly than life expectancy, then not only are people living longer, but they are also living a greater proportion of their lives free from health problems.

In March 2021, the European Commission adopted the Strategy for the rights of persons with disabilities 2021-2030 that aims to ensure that people with disabilities can experience full social and economic inclusion on an equal basis with others and live free from discrimination. The Strategy focuses on implementing the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and consolidating the EU’s body of law in this field.

In the past ten years, active and healthy ageing innovation and policy actions have been supported through joint efforts of the European Commission and the Member States, such as Active and Assisted Living Programme (AAL), European Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing (EIP-AHA), Joint Programming Initiative More Years, Better Lives, and IN-4-AHA. The Commission has also awarded grants to hundreds of R&I projects through Horizon 2020 Societal Challenge 1 – Health, Demographic change and Wellbeing, promoting the development and uptake of digital health innovations for the benefit of older adults’ health and well-being. The Commission’ Communication on enabling the Digital Transformation of Health and Cared in the Digital Single Market invited, among other things, to promote empowering people and citizens, of all age, to actively manage their health and wellbeing with the help of digital technologies.