He began his career during the 1950s folk revival and continued to record — and helped orchestrate “We Are the World” — while pursing his many other artistic and political interests.

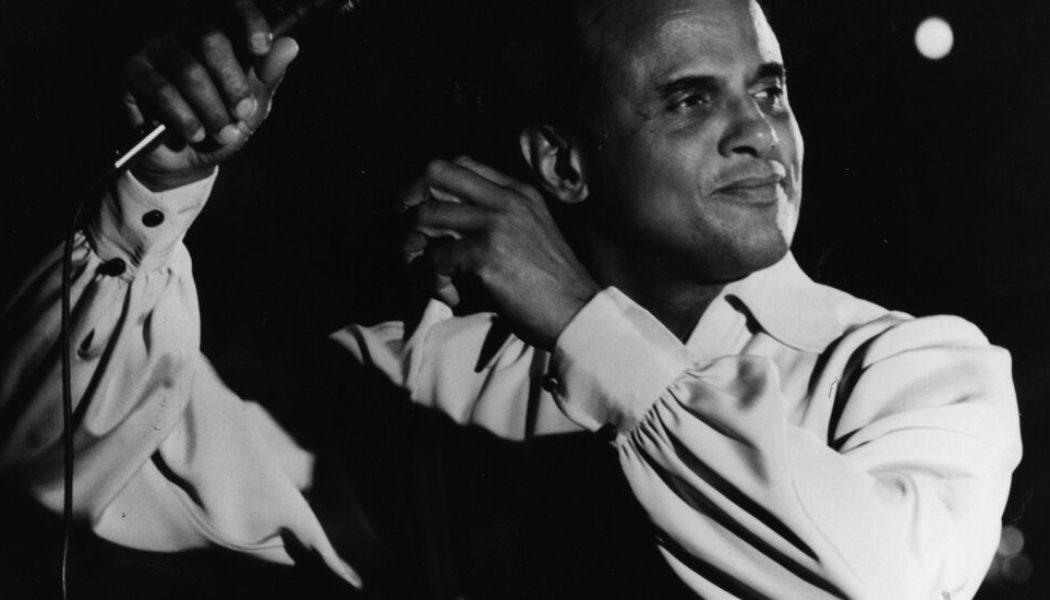

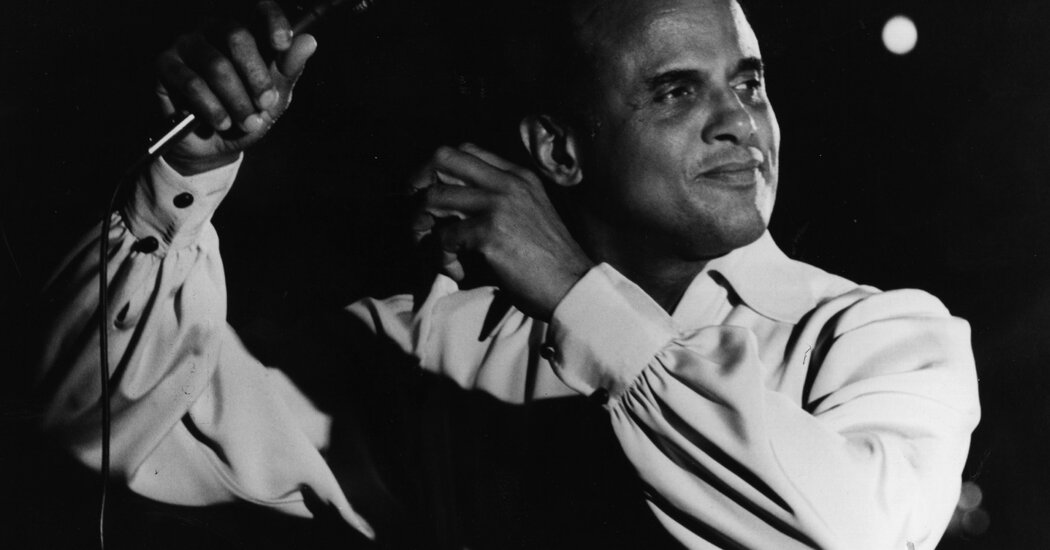

Music was the springboard for Harry Belafonte’s lifework: a career that leveraged cultural recognition toward political goals, and that recognized artistic achievements as both pleasures in themselves and symbols to wield.

Belafonte, who died on Tuesday at 96, began his career during the 1950s folk revival, a complicated and earnest moment when traditional songs — American and international — were finding new respect, while the pop mainstream was realizing that the old songs had survived because they were as memorable as any hits. The movement was filled with attempts to sanitize, sweeten and orchestrate traditional material, and many have not aged well, coming across now as pretentious or kitschy.

But Belafonte arrived with a voice that could be a tender pop croon or a bluesy near-shout. He had a genuine connection to Caribbean music after spending childhood years in Jamaica with his Jamaican mother; it’s no wonder that he was the one to turn calypso standards into American crossover hits.

Like many folk revivalists, Belafonte dug into the folk song archives at the Library of Congress, and he chose songs with full awareness of their historical implications and heritage. He was pointed in his selections, insisting on the dignity of the African diaspora. He sang work songs, love songs, spirituals, blues, calypsos and, as early as the 1960s, African music. He was also determinedly eclectic; at Carnegie Hall concerts in 1959 that were recorded for a live album, he sang “Danny Boy,” “Hava Nageela” and the Mexican song “Cucurrucucú Paloma.”

Belafonte had his commercial peak and his most prolific recording years in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the crest of the folk revival. But he continued to record — trying contemporary pop songwriters, touching back down in folk and world music — while he pursued his many other artistic and political interests. Here are 10 songs from his remarkable career.

“Banana Boat Song (Day-O)” (1955)

The clarion intro, with its drumroll and its accelerating “me say day-o,” has been parodied countless times. And the perfectly consonant harmonies from the chorus are probably a far cry from the call-and-response of the folk original. But Belafonte was making a statement by opening an album with a work song about backbreaking drudgery. And the way he shoehorns the four-syllable “tarantula” into a three-note phrase is a triumph of enunciation.

“Jamaica Farewell” (1955)

Although this song was from “Calypso,” the 1955 Belafonte album that was a blockbuster in its day, its lilting beat is a Jamaican mento, distilled down to skeletal guitar and bass. Irving Burgie’s lyrics have just enough touristic detail — “Ladies cry out while on their heads they bear/Ackee, rice, salt fish are nice” — to localize a sailor’s wistful goodbye.

“Water Boy” (1956)

A very old prison work song, “Water Boy” is stark, long-suffering and proud: “There ain’t no hammer that’s on this mountain/That ring like mine.” Belafonte sings the first half nearly a cappella with his voice leaping like a field holler, punctuated by choked guitar chords like sledgehammer strokes. Then he eases back, closer to a spiritual and rising toward falsetto, almost otherworldly in his toil and endurance.

“Mary Ann” (1958)

On the album “Belafonte Sings the Blues,” the backup group features top jazz musicians and the singing gets loose, frisky and playful. “Mary Ann” is a flirtatious rumba-blues that gives Belafonte room to slide, whoop and break notes — still completely in control, but rambunctiously.

“Cotton Fields (Live)” (1959)

Onstage at Carnegie Hall, Belafonte jazzed up a Lead Belly song about farm work and an encounter with the law in this version of “Cotton Fields,” a song that would later get a Creedence Clearwater Revival version. A walking bass line, and then a swinging jazz trio, give Belafonte a backdrop for brash, syncopated, trumpet-like phrasing. He’s reminiscing about childhood until about halfway through when, suddenly, things get tense: “I was over in Arkansas/When the sheriff asks me, what did you come here for?”

“Jump in the Line” (1961)

A calypso with an irresistible upbeat groove, “Jump in the Line” claims a lot of different authors in various versions, but seems to have come from Lord Kitchener via Lord Flea. With grainy exuberance over peppy horns and percussion, Belafonte praises the more-or-less Latin dance moves — “cha-cha, tango, waltz or de rumba” — of his girl named “See-NOR-a”; if she was a “Señora,” with a tilde, she’d be married. On a frenzied dance floor, perhaps no one cares. When Pitbull did an update in 2011, “Shake Senora,” he pronounced the tilde.

“My Angel (Malaika)” with Miriam Makeba (1965)

Miriam Makeba discovered and popularized “Malaika,” a wistful love song from East Africa, in Swahili, that she turned into an international hit. This version is from “An Evening With Belafonte/Makeba,” a split studio album of songs in African languages; it’s one of the LP’s two duets. Both singers tiptoe through the melody with the gentlest shared respect.

“Turn the World Around” (1977)

Belafonte’s voice had grown huskier when he released “Turn the World Around,” a song he wrote with Robert Freedman, but his energy was undiminished. The lyrics are based on Guinean folklore and reflect on water, fire and mountains. Brisk and intricate, it has a leaping 5/4 beat, assorted global percussion and interlocking, celebratory groups of voices.

“We Are the World” (1985)

Belafonte was the little-known impetus behind “We Are the World,” the all-star 1985 benefit single for African famine relief. To line up a younger generation of performers, he enlisted the music manager Ken Kragen, who got Lionel Richie and Michael Jackson to write the song and gathered dozens of other 1980s hitmakers. Modestly, Belafonte didn’t claim one of the lead vocal spots; he just joined the backup chorus. He can be spotted in the video at 4:20 and 5:55, eagerly singing along.

“Paradise in Gazankulu” (1988)

There’s mockery and disdain behind the jaunty beat and the major-key, Shangaan-style accordion chords of “Paradise in Gazankulu,” the title song of Belafonte’s last studio album; he recorded part of it in Johannesburg. Under apartheid — which Belafonte determinedly worked to end — Gazankulu was a so-called “homeland” created to segregate Black South Africans. “I’m just dealin’, trying not to rule you,” he sings, answered by the women: “Oh yeah ha ha ha.” In live performances, outside the restrictions of South Africa, he added, “Free Mandela!” Belafonte’s convictions never wavered.