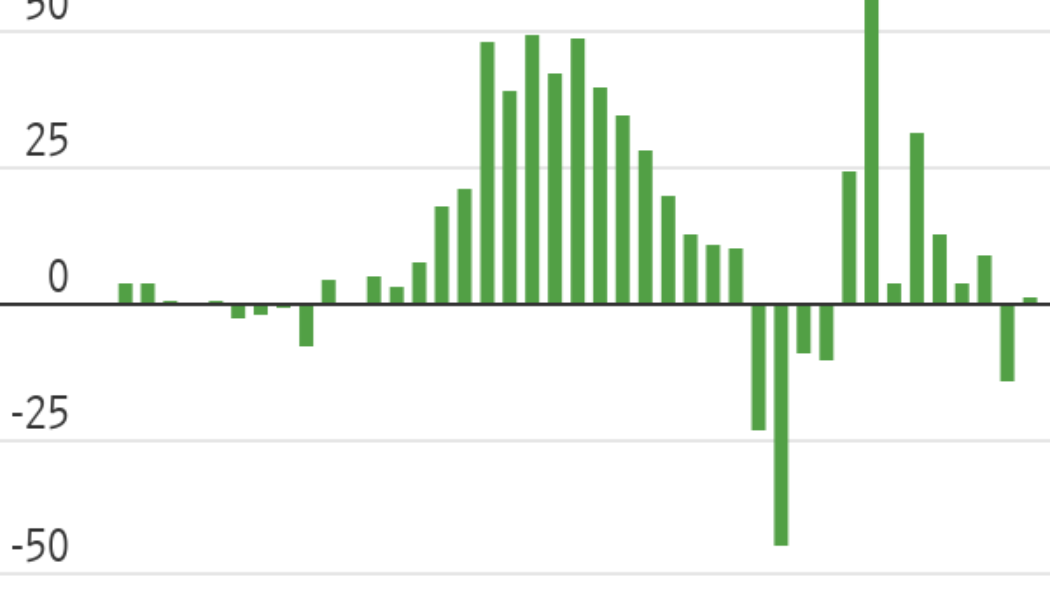

Gucci’s style is extreme, and its sales can be too, with big ups and downs.

As shoppers tire of its designs again, the Italian brand needs to show it can be more than a boom-to-bust story.

Gucci ads will be hard to avoid next month. The label recently hired a new designer, Sabato De Sarno, who will present his first collection at Milan Fashion Week in September. Gucci’s Paris-listed owner Kering has an advertising blitz planned across billboards, magazines and social media in the weeks after the fashion show—all to jump-start stagnating sales and, the company hopes, get Gucci back onto luxury fans’ radar.

Gucci has been through volatile times before. The label came close to bankruptcy 30 years ago until American designer Tom Ford was hired as creative director in 1994 and roughly tripled sales over a decade. By 2014, Gucci had lost its edge again to the point that major U.S. department store Bergdorf Goodman no longer wanted to work with the brand anymore.

That changed when Gucci’s outgoing CEO Marco Bizzarri took over in 2015 and began the gutsiest makeover so far in the luxury goods industry. He gambled by hiring then-unknown designer Alessandro Michele whose over-the-top collections were a hit with shoppers.

Michele sent models down the runway in fur-lined Gucci loafers and took over both London’s Westminster Abbey and LA’s Hollywood Boulevard for fashion shows. He launched new collaborations like one with Harlem designer Dapper Dan, better known for producing knockoffs of luxury designs for hip-hop stars in the 1980s.

“We didn’t look at focus groups. We didn’t look at consumers. We just did exactly what we wanted to do,” Bizzarri told investors at a 2018 capital markets day. This slightly reckless approach worked magic on the company’s sales.

A model walks the runway at the Gucci show during 2018 Milan Fashion Week

Photo: Pietro D’aprano/Getty Images

Gucci’s initial goal to reach €6 billion in sales, up from the €3.5 billion it made before the revamp, was smashed within two years. A subsequent target to reach the €10 billion-mark was nearly achieved by 2019. In the first four years of Gucci’s new look, Kering was the hottest stock to own in luxury, generating total annual shareholder returns above 30% on average.

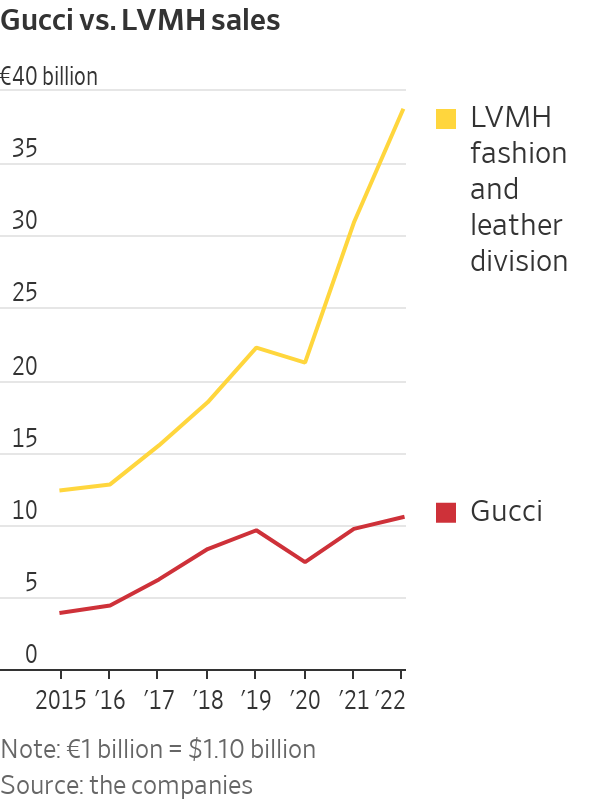

But the brand has run out of steam much faster than expected. In the second quarter of this year, Gucci’s sales rose only 1% and it missed a gold rush that enriched other luxury brands during the pandemic. In 2022, sales at competitor LVMH’s fashion and leather goods division, which includes brands like Louis Vuitton and Christian Dior, were 74% above 2019 levels. Gucci’s 2022 sales were only 9% higher.

In hindsight, Kering’s decision to slash its ad budget early in the pandemic to protect profit margins was a mistake. Powerful rivals that took the opposite approach and spent heavily on marketing won market share.

Gucci’s very trendy designs also turned off older shoppers, leaving the brand vulnerable when young consumers got bored of the look. Fickle millennials made up 60% of Gucci’s registered shoppers at one point and their interest started to slip three years ago.

Can Gucci reverse its second big slowdown in a decade? Kering has a great track record at jump-starting brands. It turned sleepy Balenciaga into a modern, successful label — at least until last year’s controversial ad featuring children holding teddy bear handbags clad in what looked like bondage gear blew up the good work. A revamp of Bottega Veneta has been another success.

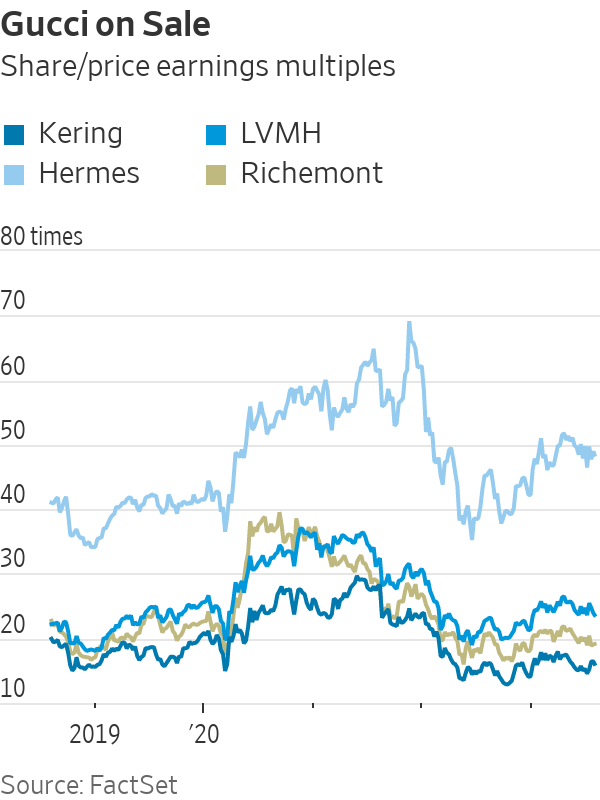

But Kering isn’t good at generating the steady, reliable growth that luxury shareholders really value. Its brands can soar before falling back down to earth. A perception that its labels are too fashionable and vulnerable to shifting trends is the main reason why Kering’s stock trades at a big discount to peers LVMH and Hermès that churn out more classic designs.

In a potentially bad sign for Kering, luxury shoppers’ tastes are becoming more conservative as the outlook for the global economy weakens. According to Bank of America’s Brand Leading Indicator, which tracks search engine data, website visits and social media followers for major luxury labels, understated brands are now outperforming flamboyant labels online. Gucci is languishing toward the bottom of the bank’s tracker.

That said, Gucci’s hit 2015 turnaround was also launched in a slow market for luxury. But Kering can’t afford to take the same risks today with its most important asset. Gucci is now a €10.5 billion label and generated 51% of Kering’s overall sales and 67% of operating profit in 2022. This is up from 34% of sales and 63% of operating profit the year Bizzarri took over.

The good news is that Kering’s billionaire owner Francois-Henri Pinault stepped in early with a management shake-up. His right-hand man Jean-François Palus will become interim CEO to make sure the launch of Gucci’s new look goes off without a hitch. A search for a permanent boss will begin later this year.

Expectations for the turnaround are low. Kering’s shares trade at a 40% discount to the European luxury average as a multiple of expected earnings over the next 12 months and it is the second-cheapest stock in the industry after Swiss watchmaker Swatch. That seems overly pessimistic. For Kering to change perceptions, though, it needs to show that Gucci can deliver steady growth. Reviving sales won’t come cheap either—ad budgets are swelling across the luxury industry as brands work harder for customers’ attention.

Even if the models in Gucci’s soon-to-be unveiled ad campaign look nonchalant, the reality behind the scenes is very different. Kering has a lot riding on the brand’s turnaround and is working furiously to convince shoppers to buy.

Sabato De Sarno is the new creative director of Gucci. He will show his debut collection in Milan in September.

Photo: Riccardo Raspa/Kering/REUTERS

Write to Carol Ryan at carol.ryan@wsj.com