Trauma can be inherited, generationally compounded by relatives who pass on their pain through destructive action or the self-destructive coping mechanisms they impart.

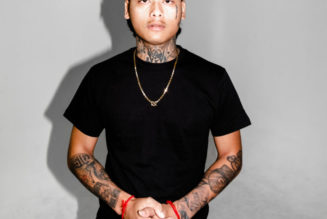

Lukah has made music for two-thirds of his life, but when the 30-year-old rapper/producer finally found his sound, he honed in on the accretive effects of trauma. On January’s When the Black Hand Touches You and late September’s Why Look Up, God’s in the Mirror, he offers Griselda-adjacent street rap as a Trojan Horse for psychology and sociology. Alternately menacing and soulful loops score Lukah’s sharp wordplay, braggadocio, hustling narratives, and avowals of pistol-grip survival. Within that framework, he couches self-empowerment and the need to address personal and inherited wounds in the Black community.

“And never ask for help cause Black men weren’t taught to self-reflect / Move through life cycles with traumas we’re expected to accept / Come fly in my shoes and you’ll see why our ancestors wept,” he raps on Why Look Up’s “Colored Ones,” condensing centuries of suffering in a slow, forceful, and enunciated flow that stresses the weight of each word.

“I want people to start dealing with their traumas. We have to get ready for the next generation to come,” Lukah says over the phone, driving through his native Memphis following an afternoon haircut. In his eyes, generational trauma is pronounced in communities afflicted by systemic racism, wherein a heightened focus on externally damaging forces hinders introspection and internal healing. He raps to break the cycle.

[embedded content][embedded content]

“We don’t look at ourselves because we’re not taught that… And when we do get taught these things, we’re afraid to dive into it because we don’t know what’s on the other side of it… It’s just a fear, and I recognized this not only in my community but in myself,” Lukah explains in conversation. “When people hear a song like ‘Colored One,’ I want it to tear through their defenses.”

Born Timothy Love, Lukah built his defenses and musical ability in the Pine Hill section of South Memphis, where well-kept multi-bedroom homes were sometimes inhabited by “the most ruthless people you know.” Gangs and drugs existed outside, but Lukah spent much of his childhood absorbing soul, gospel, and neo-soul from his mother and grandmother, both of whom were professional singers. Though he had a strained relationship with his father, he remembers discovering Scarface while sorting through the CD collection his father amassed working as a DJ. With so many familial influences, Lukah feels it “would be an insult” for him to choose a non-musical profession.

Lukah’s grandfather, however, instilled the importance of therapy and self-reflection. He founded African Americans Forming a New Tribal Existence (AAFANTE), “a safe-haven for Black people to take a look at themselves.” When Lukah attended an AAFANTE retreat at age 12, he both began to unpack mounting paternal issues and rapped on stage.

Rap remained Lukah’s sole focus in high school. He briefly made rounds in the South Memphis battle rap scene as Royal T, but he adopted the name Lukah Luciano after high school. An homage to Italian mobsters real (Lucky Luciano) and fictitious (Luca Brasi), the name held triadic significance. Lukah had watched friends and relatives become embedded in gang life, he was enamored with the mafioso rap of Kool G Rap and Raekwon, and he’d started hustling.

For several years in his mid-20s, Lukah juggled rap, hustling, and a full-time job. He coached basketball and tutored in reading and math at a Memphis grade school, believing his presence might help children lacking male role models. Wages were meager, so he funneled the money into hustling. During the few hours he had to record, Lukah was too depressed to step into the booth. He watched students attempt suicide, and he carried their respective traumas home. Each school year became more taxing than the last.

There’s another timeline where Lukah doesn’t live to see 30. In ours, he and his wife-to-be were nearly gunned down by an unknown rival while sitting in their car. Bullets pierced the glass, but they glanced off of basketballs Lukah had in his backseat. The job that was killing him saved his life.

The near-fatal experience he’d eventually recount on “The Way to Damascus” (Why Look Up…) inspired a year stint in Los Angeles, where a friend assured Lukah he’d have a better chance of building a career as Lukah (no Luciano). After one too many false promises and two scrapped albums, Lukah returned to Memphis.

Full of frustration, he reached out to Memphis blog darling Cities Aviv, whom he’d worked with on Aviv’s breakout mixtape Digital Lows (2011). With Aviv’s guidance and production, he recorded 2018’s Chickenwire. Though rawer than his most recent work, the album helped him find his voice.

“That project solidified what I’m doing now,” he explains. “I began to know why I was put on this earth and how I wanted to do this.”

[embedded content][embedded content]

COVID-19 forced Lukah to push back When the Black Hand Touches You for a year, but the delay was serendipitous. He put together his management team, found a music video director, and connected with the engineer (Hollow Sol) who helmed this year’s albums. Press and playlist rotation have mounted after Why Look Up…, but Lukah is far more concerned with the record reaching those who need it.

“There’s always a way out. That’s the most important message a listener can get from my music. You can get help, you can move away from a situation, or you can start your day off differently. There’s ways you can handle your shit. I want to help people through my music, regardless of how vulgar it is. But it’s going to be vulgar because that’s what the world is.”