Collecting satellite data for research is a group effort thanks to this app developed for Android users. Camaliot is a campaign funded by the European Space Agency, and its first project focuses on making smartphone owners around the world part of a project that can help improve weather forecasts by using your phone’s GPS receiver.

The Camaliot app works on devices running Android version 7.0 or later that support satellite navigation. The way satellite navigation works, phones or other receivers look for signals from a network of satellites that maintain a fixed orbit. The satellites send messages with the time and their location, and once it’s received, the phones note how long each message took to arrive, then use that data to figure out where on Earth they are.

Researchers think that they can use satellite signals to get more information about the atmosphere. For example, the amount of water vapor in the atmosphere can affect how a satellite signal travels through the air to something like a phone.

The app gathers information to track signal strength, the distance between the satellite and the phone being used, and the satellite’s carrier phase, according to Camaliot’s FAQs. With enough data collected from around the world, researchers can theoretically combine that with existing weather readings to measure long-term water vapor trends. They hope to use that data to inform weather forecasting models with machine learning. They can also track changes in Earth’s ionosphere — the part of the atmosphere near space. Creating better ionospheric forecasts could be relevant in tracking space weather and could eventually make Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) more accurate by accounting for events like geomagnetic storms.

Camaliot could eventually expand to include more attempts at collecting data on a massive scale using sensors present in “Internet of Things” connected home devices. “We took inspiration from the famous SETI@Home initiative, where home laptops help seek out signs of extraterrestrial life.” Vicente Navarro, an ESA navigation engineer, said in a press release.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23341150/Screen_Shot_2022_03_23_at_5.35.44_PM.png)

The project aims to gather information from all over the world — and from several different satellite constellations. There are several different Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) constellations like the US Global Positioning System (GPS), Russia’s GLONASS, China’s Beidou, or the EU’s Galileo. Japan and India also operate smaller regional constellations. An FCC order in 2018 allowed more devices to use GPS and Galileo signals together for increased location accuracy.

While older Android phones can participate in this project, the Camaliot project lists more than 50 newer models with dual-frequency receivers, which can simultaneously pull two GNSS signals with different satellite frequencies. Phones confirmed to contain dual-frequency receivers include the Google Pixel 4a, Samsung Galaxy S21, the Galaxy S21 Ultra — mostly those with high-end Qualcomm Snapdragon 5G chipsets.

Navarro says that “the combination of Galileo dual-band smartphone receivers and Android’s support for raw GNSS data recording” work together to increase the possibility of how much data can be collected solely from people using their smartphones.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23342007/Screen_Shot_2022_03_23_at_6.53.16_PM.png)

The use of at-home tech from outside participants for scientific exploration continues to grow as everyday devices include more processing power and better sensing capability. Besides the famous SETI project and similar attempts like Folding@Home, other methods have included NASA asking the public to use their phones to take photos of clouds or trees, and science apps like iNaturalist documenting animal behavior during a solar eclipse, or tracking different animal species.

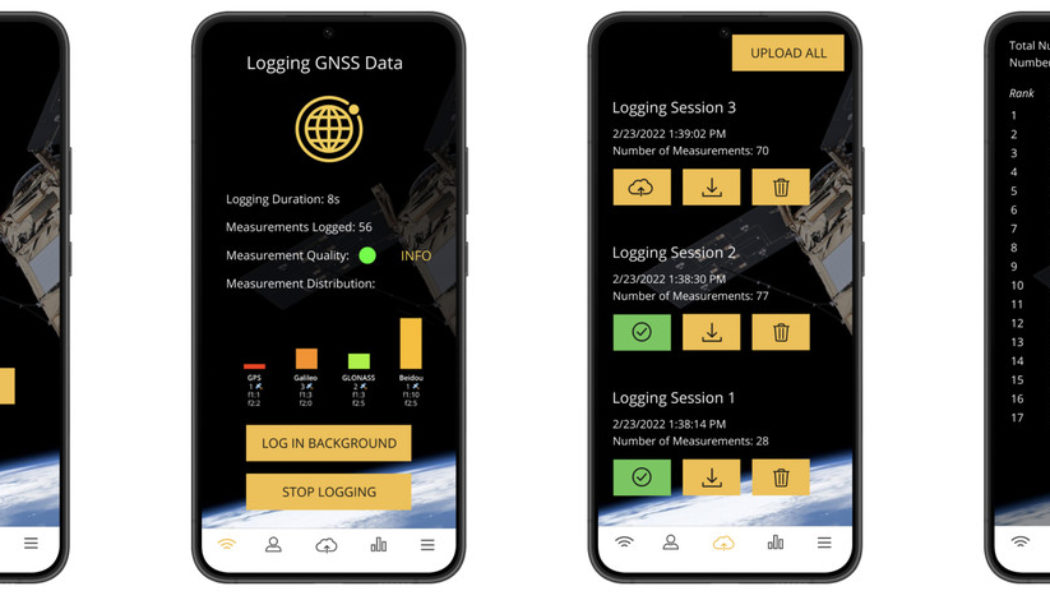

How to use Camaliot

Here’s how you can begin using the Camaliot app on your Android phone after downloading it from Google Play:

- Select “start logging” and place your phone in an area with a clear sky view to begin logging the data

- Once you have measured to your liking, select “stop logging”

- Then, upload your session to the server and repeat the process over time to collect more data. You can also delete your locally-stored log files at this step.

In addition to being able to view your own measurements against others accumulated over time, you can also see a leaderboard showing logging sessions done by other participants. Eventually, the information collected for the study will be available in a separate portal.

For registered users, their password, username, email address, and number of measurements will be stored in Camaliot’s database, but they won’t be used in post-study publications and products, according to Camaliot’s privacy policy. Specifically, Camaliot says that the need for extensive personal data is for scientific purposes and environmental monitoring and that its need for processing data is “necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest, namely for the conduction of this scientific study.”

Registered participants will also be entered into a pool for a chance to win prizes such as a dual-frequency Android phone and Amazon vouchers. The campaign will be active until June 30th.

[embedded content]