This article originally appeared in the June 2002 issue of SPIN.

It is the end of one of the world’s grandest athletic events. Seventy-eight nations have sent their best to this wintry city, and now just two champions remain, facing each other at last. The hours of practice and the years of work all come down to this one final moment.

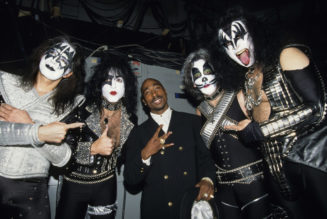

Tonight’s closing ceremony for the 2002 Olympic Winter Games is the sort of all-star, triple-axel extravaganza that makes Super Bowl halftime seem austere. Already here at Salt Lake City’s Rice-Eccles stadium, a fire-flanked Kiss have rocked (on ice!) with former Olympic figure skaters Katarina Witt and Kristi Yamaguchi; Harry Connick Jr. has sung for skating legend Dorothy Hamill; and Earth Wind & Fire have jammed with what appeared to be the USC Trojan Breakdancing Team. And soon, the finale. On one side of the stadium, the hair-metal giants from New Jersey. On the other, the hairless New Yorker NBC will call—much to his chagrin—”king of the techno beats.”

Right now, Team Moby is warming up in the green room. Wearing bookish horn-rim glasses, a brown ski cap, and the same jeans he’s had on for three days, the captain confers with his five-man rave squad over headgear. His DJ, RJ, tries on an inexplicably coveted Olympic Edition beret. “Not on my stage you don’t,” says Moby. British percussionist Pablo Cook chooses something furrier and more flamboyant. “That’s ’cause I’m a rock star, ain’t I?” Cook chides Moby. “Which you know fuck-all about.”

As if on cue, Christina Aguilera walks by, working the unlikely ensemble of black parka and bare midriff. “She’s tiny,” Moby marvels. Soon after, the die-hard vegan is confronted by the sight of Willie Nelson in a leather cowboy hat and floor-length leather coat, posing for a photo with Marie Osmond, who’s wearing a long white fur. The two just missed a half-assembled Paul Stanley, who powered by in platform boots, full makeup, and a diaphanous white peignoir.

Such surreal celebrity panoramas aren’t terribly uncommon in Moby’s recent life, which may explain the new video for “We Are All Made of Stars,” the first single from his long-awaited album 18. In the video, Kato Kaelin, Corey Feldman, Ron Jeremy, and other louche Hollywood denizens are silently observed by Moby, who wears a NASA spacesuit in every scene. In fact, Moby seems to be playing a very similar role here tonight: an alien at the party, watching everyone else have a good time.

Suddenly, a flustered functionary sweeps over to our area and removes some apparent interlopers—including two members of Team Moby—from the couch. Then Bon Jovi guitarist Richie Sambora enters, in a floor-length coat with fur collar, cowboy hat, and tinted aviator shades, flanked by two statuesque blondes. Then the Jon appears, also in tinted shades, and the two take their rightful throne.

Soon after, Moby leads his band out to play before a slightly larger audience than usual: three billion people—i.e., half the world. He presides over a soaring, pounding, arena-sized rave, with orchestra, gospel choir, neon puppets, spring-mounted acrobats, and huge inflated balls that bounce from bleacher tops to ice, where they’re kicked into the sky by a thousand ecstatic athletes. NBC broadcasts a tenth of it, finally cutting from its interviews with the color comment, “Hmm, Bon Jovi’s coming on. This should liven things up.”

Later, between sips of bottled water, Moby speaks of the spoils of stardom. “What I would say to people who haven’t experienced this is—you’re not missing a thing,” he says. “But there are probably people who are much better about it than I am. Like, Mark McGrath from Sugar Ray probably has the best time in the world. I go out, and I’m introspective and feel insecure.”

Three years ago, Moby’s third album, Play, arrived and, like a computer virus, began quietly overtaking the civilized world. Although its creator’s nervous-looking face wasn’t everywhere, the music’s mix of orchestral sweep, old blues samples, and hip-hop beats soon was. And by “everywhere,” don’t just think Stanford dorm and Omaha mall. Think Osaka train station, BBC nature show, and Latvian snack bar. Moby even composed the Olympic ceremony’s closing theme, a medley of songs from 18, a title chosen partially because numbers overcome language barriers, Play having gone gold or platinum in 26 countries.

In fact, thanks to the strange calculus of youth marketing, by 2000 “Moby” didn’t even signify a musician. It was a generational brand, official “new music” of the millennium. Offering both symphonies for a cardmember’s reverie and streety rhythms for cargo-pantsed mayhem, Moby scored an epoch. And in so doing, he stepped out from the DJ booth and became a very willing, if often perplexing, public figure.

While he’s been an island of conscientious sound bites in a sea of E! Network inanity, Moby has also spent much of the last few years in the New York gossip pages—flossing in shiny suits at awards shows, hanging with Bono and David Bowie, briefly dating Natalie Portman and Christina Ricci, and attending seemingly every party thrown in Manhattan or Los Angeles. As a final benchmark of modern celeb status, he was even grabbed, shoved, and verbally abused by Russell Crowe, who apparently didn’t feel like sharing the public men’s room of an Australian after-hours club. “He called me an American!” Moby says. Then, sometime during this giddy run, Moby’s home city ushered in another era.

“Sunday (The Day Before My Birthday),” a ghostly new song on 18, contains the following lyric, sampled from Sylvia Robinson’s 1973 R&B single “Pillow Talk”: “Sunday was a bright day / Yesterday / Dark cloud has come into the way.” This is exactly what happened last year in Moby’s Lower Manhattan neighborhood on the morning of his 36th birthday. Moby’s birthday is September 11.

One of his entries on his weblog for that day is succinct: “I can’t stop shaking and my apartment smells like smoke. What has happened? I don’t know what to say. What has happened? Oh god.”

Like many Americans, Moby spent the rest of that day freaking out, hugging friends, and drinking. “I did things that provided me with an immediate sense of comfort,” he says. These things also included making music. While nearly all the songs that would end up on 18 had already been recorded, the process of selecting, mixing, and sequencing—a huge part of a DJ’s art—had not been completed. Thus, 18 “is not a get-up-and-boogie, happy-time party record,” says Moby. “The one adjective I keep corning back to is warm. It’s very melodic, very feminine.”

The sounds and methodology of 18 are similar to Play’s, but they’re softer, more reflective. Songs like “In This World” and “One of These Mornings” refract shards of old blues and gospel records into pensive elegies. Even his attempt at a bouncy new wave song, “We Are All Made of Stars,” ends up being slightly bittersweet, with the deadpan vocal line “no one can stop us now” sounding more fatalistic than exhortative—possibly because, as Moby explains, “it’s mainly about quantum physics.”

You might call 18 a chill-out record, if only because that’s where Moby’s at personally. By now, his fans are familiar with their hero’s curious progression—from the straight-edge, vegan, Christian rave messiah and self-described “little idiot” of 1995’s Everything Is Wrong to the surly neo-punk contrarian of ’96’s Animal Rights to the Play-era image of a big pimpin’, starlet-dating sensitive male with the biggest musical IPO in history (every song from Play was signed over for commercial use). But much like the era it accompanied, the age of Superstar Moby had more than a few burst bubbles.

Some hours before his Olympic performance, Moby sits in a midsize trailer outside the stadium, reflecting on the collateral damage, such as the oft-made charge of hypocrisy. While he never made music specifically for a commercial, there was a certain irony in his appearing on MTV in a Minor Threat tee last year, representing the most righteously ethical punk band while earning royalties from Baileys Irish Cream and heading off to the Four Seasons after-party. Moby—whose “eternal soul” was auctioned on eBay (for $42)—says he still blanches from the occasional flame to his website.

“They’ll say, ‘Moby’s a huge sellout, he licenses his music to commercials, he used to be straight-edge, and now he drinks,’” Moby recounts. “And I understand why people say that. I just don’t agree with them. Before, I saw the world in very rigid, black-and-white terms. Now I see it as being more ambiguous and complicated.”

This would seem to be a large part of the new Moby, the diametric opposite of the preachy ascetic who wrote liner notes like “I know tons of people that eat meat, smoke cigarettes, drive cars, use drugs, etc…” on 1995’s Everything Is Wrong. Today, he says he would title that record Everything Is Complicated. Although he stayed vegan and Christian, he looks back at his most strident proselytizing with abject humiliation. “Around 1995 I realized that, no, I wasn’t ethically superior to people, I was just an uptight jerk.”

The journey from uptight jerkdom apparently went far beyond embracing humility and on to nightclub trawling, high-profile bacchanalia, and lots of nubile arm candy. Of course, stark ethical positions often get complicated in direct proportion to the amount of money and groupies available. The New York Post’s Richard Johnson, who runs the paper’s influential gossip page, opined that Moby is, in his piquant phrase, “getting more ass than a toilet seat.”

Moby insists otherwise. “I have a lot of female friends,” he says. “I think that confuses him.” And while he acknowledges many high-impact nights on the town, he came away from it all with more ennui than notches in his belt. He calls his new song “Extreme Ways”—with the lines “I’ve seen so much and so many places / So many heartaches, so many faces / So many dirty things, you couldn’t even believe”—a “romanticized biography.” “If I was to write a truly autobiographical song about rock’n’roll degeneracy, it would be much more banal,” he says.

In fact, the excess was underwhelming enough to leave Moby craving a different kind of celebrity. “The whole thing just makes me want to start a Jack Russell puppy farm upstate,” he says. He even cites a visit to such a farm as one of the happiest moments of his life. “Running around the yard with this gaggle of puppies chasing you,” he says wistfully. “And then you fall down, and they jump all over you. Pure, utter bliss.”

This kind of longing may be the more crucial aspect of 18’s melancholy barometer setting. While some looked askance at the flip-flops and avid commercialism of this alternative-identified artist, most assumed that Moby-in all his post-techno, shiny-suited glory—was at least having fun. Instead, he was meeting his version of the inevitable crash that faces every successful neurotic: the slow-dawning realization that even when sharing champagne with P. Diddy, he is still, as he says, “a 36-year-old inbred guy with bad posture.”

“That’s definitely a subtext to this whole record,” says Moby. “The images that fill your life are of beautiful people having wonderful times. What personal failings are preventing me from experiencing that? I find myself in that situation a lot. It’s this weird twisted combination. I’m narcissistic, I’m a megalomaniac, but I have very low self-esteem.”

Moby attributes this, in part, to growing up poor, small, and unathletic in wealthy Darien, Connecticut, where he lived with his widowed mom, who died of lung cancer in 1997. The rest he attributes to a simple lack of TRL-quality physical mojo. In the new song “Signs of Love,” he sings, “If I were beautiful / If I had the time / They would flock to me / And bathe me in the wine.” Instead, they usually hug him and turn him on to hip vegan restaurants.

“I’ve been on tour with some really handsome rock stars,” he says, naming Incubus’ Brandon Boyd, who toured on Moby’s Area:One festival, Dave Navarro, and Bush’s Gavin Rossdale. “My conclusion is that there are musicians in the world who women want to sleep with, and there are musicians in the world who women want to meet. I think I definitely fall into the latter category.”

Incubus’ Boyd senses slight humility overkill. “He has a healthy, albeit over-the-top, self-deprecation thing going on,” says Boyd. “Every time we hung out, there’d be girls around, and he’d say, ‘Yeah, they don’t wanna meet me, or that they were interested in me. It’s funny because I felt like they were all looking at him. I guess it’s just a matter of perception.”

Moby doesn’t want to appear ungrateful. “I love the fact that the people who buy my records tend to be smart and open-minded and sensitive,” he says. “There’s just a part of me that feels inadequate because I don’t look like Dave Navarro. So here it is four in the morning, I’m walking home alone, I just spent too much money buying drinks for everyone, I’m depressed.” He pauses. “And I’ll wonder, ‘Why am I doing this?’”

A couple of weeks later, Moby and I regroup at a smoke-filled East Village bar. The DJ is spinning Brit-tinged garage rock, and the studiously unkempt clientele is inspiring Moby to coin a new game: Spot the Stroke. Every time you see a fop aping the New York band’s trendy shag and new wave gear you point him out and take a drink—of spring water, Moby being back on the wagon for better health. There are roughly fifteen Strokes here tonight.

“I heard a disturbing thing today,” Moby says, after spotting a Stroke. “I was doing an interview with this British guy, and apparently one of his best friends is the spitting image of me and goes out and tells girls he’s me and gets them to have sex with him.”

Well, I ask, if that works for him, why not for you, who not only look like Moby but have the same name?

“Because I’m very shy and very picky,” he says. These days, Moby watches Behind the Music and E! True Hollywood Story for tips on celebrity survival (easy on the drugs, avoid small planes), and his lifestyle is remarkably modest. He lives in the same loft (featured on MTV’s Cribs) that he bought when Animal Rights was making him look like less than a gold mine. He’s opening a teahouse and vegan restaurant called Teany on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, to be run by his close friend and sometime paramour Kelly Tisdale. “Maybe I’m getting a little bit smarter,” Moby says. “Looking for emotional satisfaction making dinner with a bunch of friends and playing Monopoly, as opposed to going to some trendy nightclub buying $200 bottles of champagne.”

Still, years spent in the euphoria-seeking techno underground are probably hard to shake. As “Orgasm Addict” plays on the house speakers, two young women come by our table to pay their respects. One says hi. The other turns and lowers her furry white coat to reveal a tan, taut, tattooed back. I mention an item in today’s New York Post gossip column: Moby spotted generously tipping a go-go dancer at a nightclub. “What they didn’t mention is that it was a lesbian go-go bar,” says Moby. “I think that makes it a lot more redeeming.”

A little later, another Stroke comes by and hands Moby a flier for his band’s performance. In 20 minutes, he’s back asking if Moby’s planning to attend. When Moby says he’ll be out of town, the guy asks for the flier back: “Sorry, I ran out.” Sitting here watching such egregious celebrity magnetism, I think for a moment that it seems Moby just might be off to the puppy farm. But more likely, he’s doomed to play the conflicted, post-alternative, megalomaniacal supernerd who makes world-reaching music alone in his bedroom. Which is more than enough to make anyone a little insane.

Not that there isn’t a bright side. “I think what might have killed a lot of these successful alternative musicians was this sense of entitlement,” Moby says. “They started to feel like rock stars. I feel like if I’m successful and appear on TV and sell a lot of records, then I’m just approaching the level that everyone else is already at.”

He pauses and makes what sounds like a mental note. “When things settle down, I’ll find a good therapist.”