The longtime artistic director of men’s wear at Fendi, a brand founded by her grandparents, no longer feels she has to prove that she earned her place.

IT’S THE DAY before the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, Italy’s unofficial kickoff to the Christmas season. Tomorrow, the streets of Rome will explode with fireworks, public displays of supplication, singing, soccer matches among young priests and an appearance by Pope Francis near the foot of the Spanish Steps. But on this quiet early December afternoon, the 62-year-old designer Silvia Venturini Fendi — the third-generation matriarch of the Fendi dynasty, and one of the few women at the creative helm of a luxury fashion house, inherited or otherwise — is mostly preoccupied with how to fix a sweater. There are five weeks until Fendi’s fall 2023 men’s wear show in Milan and, at a meeting to go over the new collection at the brand’s headquarters, she’s demanding some changes.

A model emerges in a gray cashmere top embellished with reflective F-shaped and circular paillettes. “It’s sexy,” says Venturini Fendi, running a hand through her short sandy blond hair. “But is it Christmas tree?” Then comes a pair of luxurious athleisure pants; she wonders if, without a fly, they’re “a little soccer mom.” Distinguishing her compliments from her criticism isn’t always easy: She’s spent the past few hours describing pieces as “a bit like a cult,” “a bit wormy,” “very Rick Owens,” “very hmm,” “very Juicy Couture” and “very our friend we don’t like.” That last one is high praise.

Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” plays softly as the models come out in sumptuous layers of wool and cashmere. Disco, a symbol of freedom from Venturini Fendi’s youth and the musical equivalent of the brand itself — playful, influential, not always given the credit it deserves — partly inspired the designs, but she refuses to pinpoint references, preferring instead, as she puts it, “to really work on the garments more than the idea of, ‘Who is this man?’”

The Fendi client is a little hard to describe: He’s neither collegiate like the Americans (Ralph Lauren, Tommy Hilfiger), louche like the French (Celine, Saint Laurent) nor suave like the other Italians (Armani, Zegna). “We do very luxurious garments, but they have to look like they’re not luxurious at all,” says Venturini Fendi, who isn’t interested in affectation. For her, style is about lightness — delicate fabrics, subtle details, an effortless attitude — which has been central to the Fendi mission since the 1980s, when the brand introduced reversible fur coats with minimal bulk. “I hate perfection,” adds the designer, who has styled tuxedo blazers with jogging pants (fall 2007), made a distressed jean jacket from leather (spring 2015) and offered pastel-toned crop-top suiting (spring 2022).

After taking over as the artistic director of men’s wear and accessories in 1994, Venturini Fendi began questioning notions of masculinity with each bare midriff, translucent nylon trouser or quilted blouson well before the mainstreaming of genderless dressing. “She just wants to unhinge every male certitude,” the fashion journalist Tim Blanks once wrote. As a young girl, she always preferred navy, gray, brown and black to pink. “I never felt that there was this kind of division,” she says.

Although Venturini Fendi can be direct, she’s not cruel, delivering opinions with the wink of a stern grandmother who’s got candies stashed in her pocket. Surrounded by racks of prototypes and fabric swatches with names like Quinoa and Moonlight, she sits at a long table among a few members of her team. Another model approaches them in a dusty pink pullover with a diagonal gash down the front — a wearable Lucio Fontana painting, maybe, or something from the costume department of a slasher film.

“I feel … ,” says Venturini Fendi, squinting through her glasses at the laceration. “I don’t know.” One of her designers reaches for a pair of scissors. Understanding her intention, Venturini Fendi nods for her to proceed. She extends the hole in the garment by a few inches, then glances back at Venturini Fendi, who nods again. The designer then snips the last bit of fabric holding the bottom of the sweater together. A member of the group gasps as it flops open, revealing an asymmetrical gray tank top worn underneath. Venturini Fendi smiles. “A twin set,” she says, pushing up the sleeves of her own cream cardigan. “Very nice.” Then she corrects herself: “A him set.”

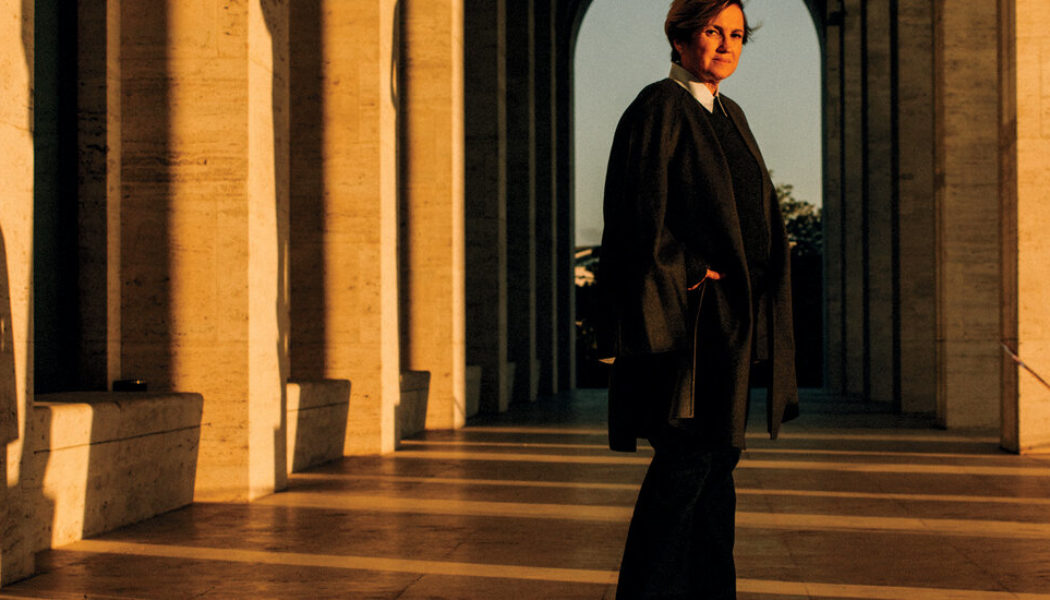

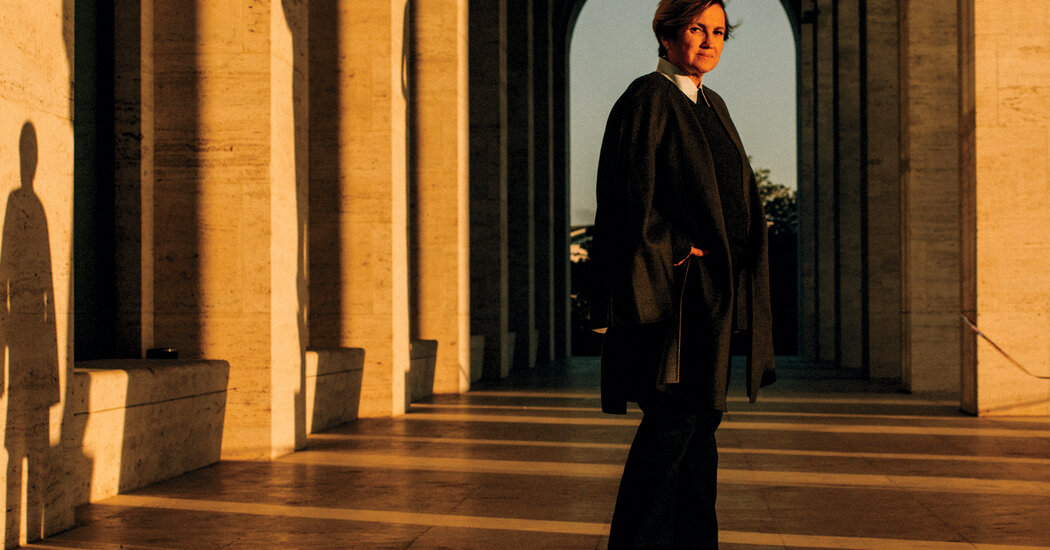

LATER THAT EVENING, a full moon casts dramatic shadows across Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana, the once abandoned 1943 Fascist monument that Fendi moved into in 2015. The windows, framed by uniform rows of travertine arches — six down and nine across, supposedly to match the number of letters in Benito Mussolini’s name — emanate an eerie glow. Venturini Fendi is at her desk in what she calls the Aquarium, a glass-walled corner office overlooking Rome’s business district.

“I like my normality with a touch of perversity,” she says, reflecting on some of her favorite pieces in the new collection: a cap with fabric fringe meant to resemble hair, a cashmere sweater with a single built-in glove and a shearling handbag in the shape of a baguette (not the endlessly iterated flap-handle It bag she created in 1997 but an actual loaf of French bread). “Every piece is normal in a Fendi way.”

Yet despite the relief of having completed a successful run-through, she’s already planning the next round of alterations; satisfaction, she believes, enfeebles creativity. “I always think I could have done better,” she says. Humility is rare in an industry where egos get mistaken for genius, but Venturini Fendi’s has served to protect her. Even now, when no one is questioning her contribution to fashion, she can sometimes feel a little insecure. “People make you feel like that,” she says. They think, “ ‘Is she good? Or is she there because she’s “the daughter of”?’” There’s a sadness in her tone; after 40 years and more than 50 collections, she’s proud of her pioneering work as the head of a women-led empire, and of the community she’s fostered there. “I belong to this place,” she says.

It wasn’t so long ago that inheriting the family business, particularly in Italy and especially in the luxury sector, was considered a noble act of duty, rather than proof of entitlement. Control of Gucci, established in 1921 by Guccio Gucci, was passed down to three of the founder’s sons, Aldo, Vasco and Rodolfo, and later to Rodolfo’s only son, Maurizio. Prada, a leather goods boutique opened by the brothers Mario and Martino Prada in 1913, was taken over in 1958 by Mario’s daughter, Luisa, and eventually her three children, including Miuccia, the brand’s longtime lead designer. And the shoe company that Salvatore Ferragamo started in 1927 remains in the family.

But even in Italy, dynasties are beginning to diversify, making Venturini Fendi ever more of a holdout: Following years of infighting among the Guccis, the company was sold in 1993 (and later acquired by the France-based conglomerate now known as Kering); in 2020, the Belgian designer Raf Simons was appointed co-creative director of Prada alongside Miuccia and, in January, Miuccia and her husband, Patrizio Bertelli, stepped down as co-C.E.O.s of the group. Although the Ferragamos are still involved in the business side of the brand, its new creative director, Maximilian Davis, is a 27-year-old from England. Yet when the multinational luxury goods group LVMH bought a controlling stake in Fendi in 2001, its chairman, Bernard Arnault, validated Venturini Fendi — and perhaps surprised others in the industry, who saw the acquisition as a moment for reinvention — by asking her to stay. “When we sold, it was kind of a liberation,” she says. “Because I said, ‘Finally, I’m here because I am who I am, and not because of the name.’”

IMAGES OF LINDA Evangelista wearing Fendi are plastered throughout Rome’s Leonardo da Vinci airport. In the historic heart of the city, a tree of luminescent metal Baguettes has been erected in front of the five-story Palazzo Fendi, which houses the company’s luxury hotel and flagship store. Inside the boutique, the brand’s monogram — a pair of inverted, mirror-image F’s in a sans serif font — has been stitched, printed or carved onto silk scarves, high heels, porcelain teapots, candleholders, dog coats, Polaroid cameras and baby strollers. “I get so emotional when I go to a new city and see big billboards with Fendi on it,” Venturini Fendi says. “My aunts, my grandmother and grandfather, how happy they would be.”

Fendi, like many of its Italian counterparts, didn’t begin as a fashion house. In 1926, Venturini Fendi’s maternal grandparents, Adele Casagrande and Edoardo Fendi, opened a small leather goods store and fur workshop on Rome’s Via del Plebiscito. After Edoardo died in 1954, Adele continued to run the company with their five daughters — Paola; Franca; Carla; Alda; and Venturini Fendi’s mother, Anna, now 89 — who had napped and played in the family store as children.

Over the next several decades, Fendi transformed into a global powerhouse — along with Gucci and Ferragamo, a member of what might be called Italy’s Luxury Generation. Hollywood actresses and European royalty were drawn to its modern handbags and coats, and to the family’s dedication to artisanship. In 1965, the sisters began a lifelong collaboration with the German designer Karl Lagerfeld. Although he’s more immediately known for revitalizing Chanel tweeds, Lagerfeld also revamped Fendi’s trademark fur coat, reconstructing it into everything from a black sable trench that was valued at a million euros (fall 2015 couture) to a multicolored mink with a floral motif that took more than 1,200 hours to produce (fall 2016 couture). He held the post of creative director of fur collections and later women’s ready-to-wear at Fendi for 54 years until his death in 2019; the partnership was the longest of its kind between a designer and a house. While Lagerfeld’s collections reflected passing trends — he did his own take on Halston one season, and on punk, too — he gave Fendi a sense of opulence without ostentation, an elevated articulation of the sisters’ pragmatic elegance.

Unlike Lagerfeld, Venturini Fendi is often characterized as a reluctant designer with a rebellious spirit or, as Dana Thomas wrote in The New York Times in 1999, “the bad girl of the Fendi clan.” And yet, except for a brief hiatus in her 20s, she has devoted her entire life to the brand. At 6, she appeared in a Fendi campaign wearing a bomber jacket made of beaver pelts with a matching hat. In fact, she’s hard-pressed to surface any early memory that doesn’t involve fashion: the runway shows; the family dinners that would inevitably devolve into long, sometimes heated business meetings; the hours she spent on Lagerfeld’s lap watching him sketch. “Everyone thinks that fashion is so open-minded,” says Venturini Fendi, “but my family had strict rules: You studied or you worked.” Having seen how much time her mother spent on Fendi-related matters, Venturini Fendi, like most teenagers, preferred to go roller skating with her friends. “I knew that the moment I started working, it was the end of my personal life,” she says.

In 1980, at the age of 20, she narrowly avoided an abduction attempt. During Italy’s Years of Lead, an era marked by assassinations and other acts of political terrorism, the heirs of rich and powerful families — including, most famously, John Paul Getty III, the grandson of the oil tycoon J. Paul Getty — were targeted by the Mafia for ransom. “Thank God I was very smart, and they didn’t succeed,” says Venturini Fendi, who grew up thinking it was normal to ride in cars with bulletproof windows. She doesn’t like to remember that period. “This fear doesn’t go away. Never.”

To protect her daughter, Anna sent Venturini Fendi to live in Los Angeles. (Giulio Cesare Venturini, Venturini Fendi’s father, died when she was a teenager.) But even there she remained tethered to the company, doing P.R. and working at a Fendi shop. While in the States, she fell in love with Bernard Delettrez, a French jewelry designer who could offer something her prominent family couldn’t: a day off.

Delettrez and Venturini Fendi escaped to Rio de Janeiro, which she remembers fondly as “wildlife mixed with wild life.” She looks back on that time with what she calls “saudade,” the Portuguese term for nostalgic longing. “So far from fashion,” she says. (These days, she tries not to visit too often: “Every time I go back, I question my life.”) When she returned to Rome at 23, she was pregnant with her firstborn son, Giulio, who now helps run his aunt Ilaria’s organic farm just outside of the city. Although having a child at that age could have derailed her career, Venturini Fendi, who separated from Delettrez years ago — they never married — was emboldened. “It was kind of like, ‘OK, now I have a family and I have to grow up immediately.’”

IN THE FENDI offices, there’s an atelier and workshop where dozens of furriers turn chinchilla and bobcat pelts into intricately detailed coats. Fendi, for whom fur is still a significant part of the business, has been experimenting with a new alternative using keratin, the main protein in hair. Alexandre Capelli, LVMH’s group environmental deputy director, told Vogue Business last April, “Even if the quality of fake fur has improved in the last year, it’s still not at the level of natural fur. We think that with this innovation, we should be able to achieve this level of quality — very close to natural fur.” Down the hall, an archive contains stacks of Baguettes and Peekaboos (a bivalved handbag connected with a twisting lock that Venturini Fendi introduced in 2008); leather trunks (one of them, with the initials “S.P.” on it, belonged to Sophia Ponti, better known as Sophia Loren); and walls of framed photographs, including a black-and-white portrait of Venturini Fendi’s mother and her aunts wrapped in furs and surrounded by shopping bags with the double-F logo on them (it stands for “fun fur,” not “Fendi family”). There are also some of the tens of thousands of sketches that Lagerfeld made for Fendi, like the fur pantsuit he named l’abominable femme des neiges, or the Abominable Snow Woman.

Nobody had a bigger impact on Venturini Fendi than Lagerfeld, who encouraged her in 1992 to stop designing for Fendissime (Fendi’s onetime diffusion line), where she’d been employed since returning from Rio, and to work for him at Fendi. “I was very pleased it was Karl who asked me, because if it’s your mother, it’s not the same,” she says. Despite Lagerfeld’s unpredictability — “He’d say, ‘We work at 3,’ and he’d arrive at 7,” Venturini Fendi recalls — he became her friend and mentor. Although she doesn’t sew or sketch, Venturini Fendi learned a lot from Lagerfeld about how a designer should be. “Karl had a great sense of humor,” she says. “If I counted all the hours I’ve been at Fendi, … I have to laugh.”

When Lagerfeld died, Venturini Fendi temporarily took over as the artistic director of women’s wear. The next year, in 2020, Fendi announced it had hired a permanent replacement: the British designer Kim Jones, 43, also the artistic director of Dior Men, and the men’s artistic director at Louis Vuitton before that. If Lagerfeld was sui generis, Jones is more like Venturini Fendi, an enthusiastic collaborator whose work often telegraphs a sense of creative collision and collusion, rather than a single distinct style.

Shortly after Jones’s appointment, he convinced Venturini Fendi to hire the second of her three children, her daughter Delfina Delettrez Fendi, 35, who brings her own Surrealist vision — ruby earrings shaped like lips, a Carrara marble cuff made to look like a tightly gripped hand — to the house as artistic director of jewelry. “I would never say, ‘Please, can I have my daughter working with us?’” says Venturini Fendi, but she’s glad that Jones suggested it. Delettrez Fendi, she says, is “supertalented.” And there’s perhaps another reason she’s happy to have her on hand: It means that another generation of Fendis is working at the house. There’s so little loyalty in luxury fashion; heritage is too often nothing more than a marketing byword. But despite Venturini Fendi’s occasional ambivalence about her life at the family company, her daughter’s presence is a reminder, a thread connecting not just the present but the future to the past.

A MONTH LATER, at the fall 2023 men’s wear show, Delettrez Fendi sits front row in one of her mother’s hair hats. Some of the models wear earrings and chains she designed with a cascade of five connected F’s — one for her grandmother and her four great-aunts. Venturini Fendi takes her final bow on an elaborate set shaped like an immersive pinball machine. Soon, she’ll be swarmed backstage by journalists — her least favorite part of the job. It’s not that she can’t take a compliment; it’s that she doesn’t believe them. “Nobody will say, ‘I didn’t like it,’ or, ‘It wasn’t what I was expecting,’” she had said back in her office. “But then they’ll write what they really think.”

For now, a Giorgio Moroder soundtrack is pulsing through the speakers and, on the runway, Venturini Fendi seems briefly transported back to the 1980s, when, as a young woman representing Fendi at New York trade shows, she used to spend all night dancing and skating at the Roxy, which was known as the Studio 54 of roller rinks. “It was magic,” she had said about that time in her life. “Anything could happen.” Tonight, however, she’ll go to bed early. The next show is just around the corner.

Models: Baek at Premium Models, Kuba at Crew Model Management and Tahirou Ka at Major Models. Hair by Kota Suizu at CLM. Grooming by Vanessa Forlini at Making Beauty Management. Casting by Gabrielle Lawrence at People-file. Production: Hotel Production. Photo assistants: Jessica Ellis, Gemma Lawrence. Stylist’s assistant: Alessandra Filieri