Markets aren’t infallible, and sometimes their read on the situation is wrong. But often when they’re wrong, they skew toward pessimism, reacting quickly and aggressively to negative news or even the hint of it. At the end of 2018, for instance, stocks plummeted 20 percent or more based on the fear, unfounded, that rising interest rates would cripple activity. It’s often been said, derisively, that Wall Street has correctly predicted nine of the past five recessions.

In the past few weeks, however, finance-land has flipped that script and is reflecting substantial optimism. What’s going on?

Usually market moves are at least partly in sync with real-world problems. When global markets teetered in the fall of 2011, it was because of legitimate concerns that Greece was about to leave or be forced out of the European Union, and that doing so would create a negative cascade that could damage the global financial system. When markets plunged in early March as the coronavirus crisis hit the West, that was fully in sync with the imminent shutdown of the real-world economy.

No longer. Just as nearly every state in the U.S. has shut down and ramped up the urgency of its coronavirus response, as the president flips from floating an Easter reopening to talk of a long war to get back to normal, and as countries ranging from India to Japan institute their own draconian lockdowns to halt the spread, financial markets have sharply recovered from their low point on March 23.

This volatility could, of course, simply mean investors and the computer programs that trigger a considerable portion of trading activity are flailing wildly, buffeted by the news du jour and grasping for certainty about the economic and epidemiological future that simply doesn’t exist right now. But even here, volatility in stocks as measured by the VIX index is down nearly 50 percent since its mid-March spike, and credit markets have been downright placid.

You’d think, given the real-world news, that the Wall Street consensus would be pretty dire. For the next three months at least, and likely the next six, very few companies will see anything approaching the level of earnings that they had last year. Publicly traded casino companies like Wynn resorts? Cruise lines like Carnival? Airlines like Jetblue and United? Auto companies like Ford? Retailers like Gap? Restaurant chains? All of those have seen massive stock declines for sure; but if you consider the collapse in their predicted revenue, combined with zero clarity about how and when that will rebound, arguably stocks should fall much further.

The same could be said of municipal and state bonds. With the economy nearly frozen, local and state governments have the prospects of seeing their tax receipts slashed in half for a period of the year, and unlike the federal government, their capacity to borrow is much more constrained. Yet none of the municipal bond markets have collapsed.

So, are markets living in some fantasyland? Possibly. But there’s another way to look at it that gives us all cause for some optimism. Financial markets aren’t reflecting what’s happening now, or even “pricing in” the next three months. Quite the opposite. They are looking beyond the economic damage of the next three to six months, and seeing a brighter future.

When you consider what the Federal Reserve and Congress are doing, as well as what’s happening right now in China, Wall Street might not be so crazy after all. There are good reasons to think that the world we live in might feel different in 18 months, but the economy will be roughly intact—or, at least 80 percent intact, which is where the Dow is now relative to the beginning of year.

In part, this is because of the huge backstop the U.S. government and central banks are providing. The Federal Reserve and other global central banks have committed to buying just about everything short of stocks in order to bolster financial markets and stave off collapse. That is allowing markets to trade as if everything were bad but not catastrophic.

Then there are actions taken by Congress in the United States and by every sovereign government in the developed world to replace a significant portion of lost business and wages. In Europe, governments are committed to directly paying wages for months. In the United States, assuming Congress acts again this week, the government will provide more than $600 billion in small business loans to cover payroll for the next three months, loans that will then be forgiven if businesses keep workers on payroll. That is on top of $500 billion to be distributed to larger companies, plus direct checks to individuals. In essence, governments are acting as if there could be zero economic activity in the next three months and are instead footing the bill for the entire economy. Government spending won’t prevent a recession; but it could be prevent a long, protracted one that would feel like a depression.

But there is something else going on as well, which is that markets in the past week are reflecting a sentiment that the worst-case scenarios predicted by public-health officials may not come to pass. Already, because of aggressive social distancing and stay-at-home orders, the models of last week are being revised downward. Fauci on Wednesday expressed strong conviction that schools will indeed reopen in August, which itself would augur for much broader resumptions of activity. Gov. Andrew Cuomo has already begun planning for the restart of the hard hit New York-New Jersey region.

There is, as well, one real world case that points in a different direction than “everything will be changed forever”: China. After months of lockdown, China is reopening; restaurants are serving customers; schools are admitting or about to admit students; factories and stores are open. Not everything is normal; movie theaters remain closed, large gatherings untenable. While the death toll may have been higher in China than reported, the resumption of activity cannot be so easily faked.

Should we end up following that path, and this week there have been multiple indications of flattening curves in New York and perhaps Washington and California, as well as Spain and Italy, then markets that are down but haven’t cratered are reflecting a reality that the majority of us appear to be heavily discounting right now.

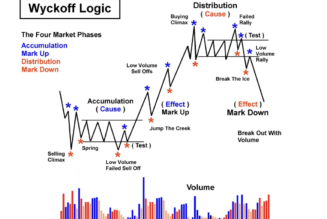

It is, of course, possible that short-term market euphoria is misplaced and will prove fleeting. On Wall Street, bear markets are full of “traps,” where short-term rallies lull people into believing, falsely, that the worst has passed. But it may be that markets are digesting information about probable futures more rationally than humans are just now. If that is the case, the sum of our fears, fears that seem more justified than at any point in our lived past, will once again not come to pass. We will look back at these months as a tragedy but not as a new normal.