In China, luxury brands have far fewer millionaires to sell to than in the U.S. But the American market has its drawbacks.

Photo: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg News

America can sometimes seem like an emerging market for Europe’s big luxury companies: It has booms, busts and vast potential that hasn’t been fully realized.

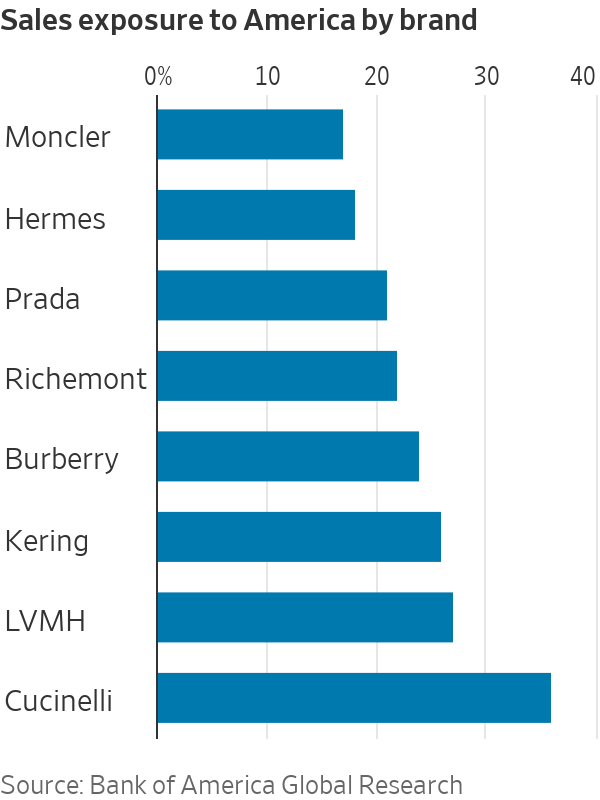

In the U.S., the fortunes of top designer brands varied widely in the three months through June. Kering, one of the worst performers, said Thursday that sales in its North America division were down 23% in the quarter compared with the same time last year. Its main brand Gucci is flagging, while Balenciaga is still suffering after a controversial ad damaged the label last year.

Burberry and Prada were also down in the Americas region, by 8% and 6% respectively. Even the company behind jewelers Cartier and Van Cleef & Arpels—supposedly recession-proof labels that mainly sell big-ticket items to the super rich—said demand has been weak.

At the other end of the spectrum, Birkin handbag maker Hermès said Friday that its business in the Americas rose 21% in the latest quarter. Its stock was up 4% in morning trading, making it the top performer in the Euro Stoxx 50 index. Pricey independent Italian label Brunello Cucinelli is also still growing stateside.

The U.S. market has sometimes been a conundrum to Europe’s luxury brands. America has more dollar millionaires than any other country in the world: According to Credit Suisse, four in 10 of the world’s millionaires live in the U.S., compared with one in 10 in China. But luxury sales haven’t lived up to the promise. London-listed retailer Watches of Switzerland estimated that per capita spending on posh watches in the U.S. is around a third the level of the U.K.

One problem for luxury brands is that the U.S. market can be very promotional, and American consumers like a bargain. Pressure to offer deals led brands to pull their products out of U.S. department stores and sell through their own boutiques, where they have greater control over prices.

It is also an expensive place for brands to promote themselves. Compared with the Chinese market, a bigger share of U.S. advertising happens through traditional channels such as fashion magazines and TV, where the cost of campaigns can run to hundreds of thousands of dollars. This has made it hard for all but the biggest brands to get noticed.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

Will luxury goods companies be increasingly dependent on China for sales? Why or why not? Join the conversation below.

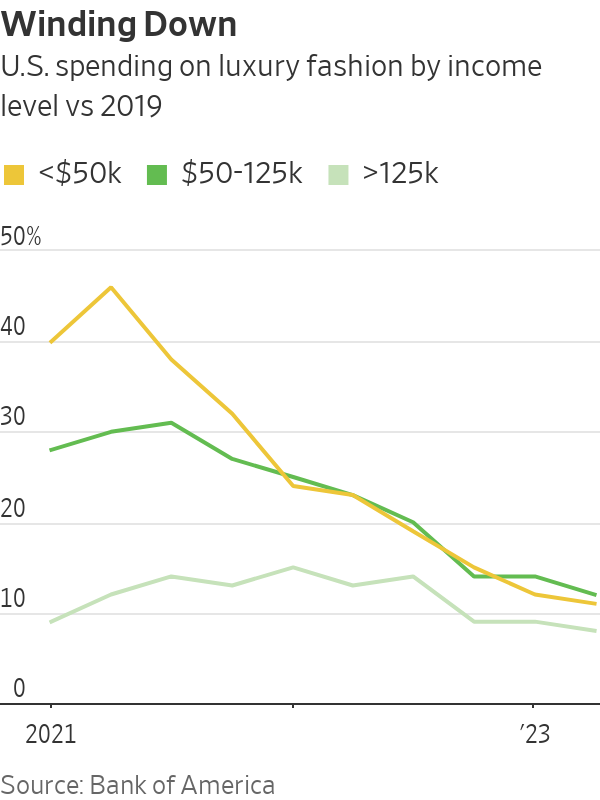

The market changed dramatically during the pandemic, however. Americans flipped from accounting for 22% of global luxury sales in 2019 to 33% in 2022, based on Bain & Company data. The shift almost doubled the size of the U.S. luxury market in only three years to €116.5 billion in 2022, equivalent to $128 billion at today’s exchange rate.

The boom was likely supercharged by stimulus payments. In March 2021, the U.S. government handed $1,400 to most Americans. In the quarter after the checks began to be distributed, people earning less than $50,000 a year spent 46% more on luxury fashion than they did in the same period of 2019, according to Bank of America data.

That trend is now losing steam. Demand for the lower-priced goods of luxury brands such as sneakers that target so-called aspirational shoppers is very weak. Sales of cognac have seen a “brutal” slowdown in the U.S., according to the world’s biggest luxury group, LVMH Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton,

which reported results on Tuesday. Second-tier cities such as Austin and Nashville, which wouldn’t normally be on luxury brands’ radar but boomed during the pandemic, have lost momentum.

There are valuable lessons for brands at the end of the gold rush. Americans’ appetite for luxury has been whetted, and they seem happy to splurge on classic goods offered by companies like Hermès no matter the outlook. Even with the recent slowdown, U.S. shoppers across all income levels are still splashing out around a 10th more on luxury goods than they were in 2019, credit-card spending data shows.

At the same time, companies that rely on less wealthy shoppers, or sell loud designs, will probably struggle to grow for a while. And the need to invest in advertising to revive U.S. sales could reduce the industry’s profit margins, which have grown fat in recent years.

Luxury’s pandemic gilded age is ending, but nor is the U.S. market going back to where it was.

Write to Carol Ryan at carol.ryan@wsj.com