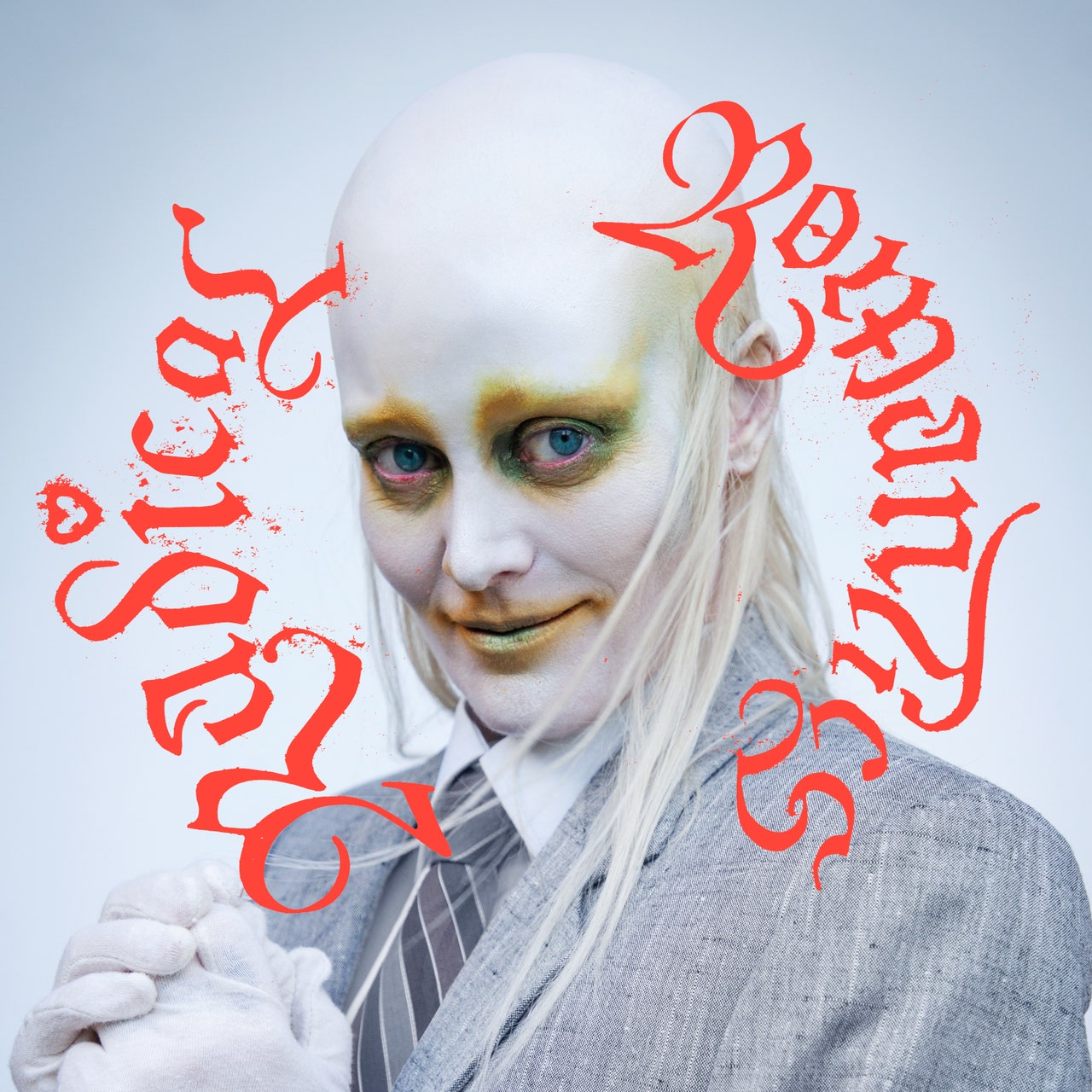

Listen to Fever Ray and learn to recognize the unrecognizable. On one of their new songs, “Looking for a Ghost,” Karin Dreijer plunks out a tune inspired by Henry Mancini’s “Baby Elephant Walk,” stacking calliope synths behind the berserk couplet “eating out/like cannibal” and a Bob Marley quote. Then this horny little collage of references slowly assumes shape: In their slyly sincere way, Dreijer is writing a personals ad. “Looking for a person/With a special kind of smile,” it reads. “Teeth like razors/Fingers like spice.” You know, someone who gives you that tingle. Lisbon producer Nídia fits them with a corkscrewing synth and a beat that lurches and jingles. “Looking for a ghost in the midst of life,” Dreijer says, which could almost be a literal complaint about queer dating in one’s forties, and then they wink: “Asking for a friend/Who’s kind of shy.”

Shy or not, we’ve come to know Dreijer better since their days as a shadowy beaked figure alongside their brother Olof in the heady electronic project the Knife. As Fever Ray, they make synth-pop with mucous membrane and muscle memory, writing songs that throw off unlikely hooks (“mustn’t hurry”) and chart new orbital paths around large pop structures. With a title like a college seminar and Dreijer’s signature blend of kink and theory, Radical Romantics is essentially a collection of notes on love. Love—whether sexy, overwhelming, or vengeful—links together the recurring motivations of the Fever Ray catalog: curiosity and exploration, family born and chosen, sexual freedom and pleasure. In the past, perhaps, they have sung about love as something vague and unknowable. Now they go looking.

In the run-up to 2017’s vivid and lustful Plunge, Dreijer talked about their dating experiments with candor that came as a surprise. “I’ve been on Tinder,” they said then, presumably with a glint in their eye. Plunge was no stranger to love but also called it “the final puzzle piece.” Anybody will tell you that to find it, first you must look within. Like many, Dreijer shifted their priorities during the pandemic, saying recently that the past few years provided them space to practice patience. In a modern culture that promotes love as instant gratification—keep swiping—Fever Ray now search elsewhere. Referencing bell hooks’ influential All About Love and Gift From the Sea, Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s 1955 spiritual bestseller, Dreijer is on an inner quest through a region of adult heartache that’s less often explored.

There are a typically savvy collection of collaborators: Along with Nídia on “Looking for a Ghost,” there’s Olof, whose sorcerous trap doors turn the album’s first four tracks into an unofficial and much-anticipated Knife reunion; English producer Vessel, on the standout “Carbon Dioxide”; Aasthma, the production duo of Peder Mannerfelt and Pär Grindvik, on “Tapping Fingers”; and Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, whose creeping industrial groans give Dreijer’s reality the weird thrill of fiction. The baleful mood kicks in on “Even It Out,” a small act of cosmic reckoning: “This is for Zacharias/Who bullied my kid in high school/There’s no room for you/And we know where you live!” Dreijer yowls. Where Lydia Tár stoops, Dreijer stands. “I do things methodically,” they sneer, slicing up the word as implied violence: “M-m-m-m-m-methodically.”

Radical Romantics doesn’t have a line like Plunge’s “this country makes it hard to fuck.” It’s slipperier and often slower, working through problems that take longer to solve even as the sky darkens. “Did you hear what they call us?” Dreijer moans on opener “What They Call Us,” a song written from “a very queer perspective.” But we cannot hear the despicable words, only turn to one another anxiously for confirmation that we are not alone yet. Dreijer’s asphyxiating delivery implies danger—the silent alarm or the spreading cloud—but for the moment, love shields us and we proceed through a beat that licks like flames at the heel. Everywhere their words are full of the exquisite caution of experience, as on “Shiver,” where a high pitch shift seems to throw a question into the hands of its recipient: “Can I trust you?”

Sometimes you cannot. Sometimes love is bad for you. Sometimes the fire is too hot and the glove melts at the touch. This is the love of obsession and distraction, like the whining mosquito voice that echoes Dreijer’s words on “Carbon Dioxide”: “Hy-y-y-per focus!” (Later they quote from 1 Corinthians 13, the memorable Bible passage on love: “If I speak in the tongues of men or of angels, but do not have love, I am only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal.”) We’ll need new tools to survive, so on the eerie “New Utensils,” they supply practical knowledge of how to build a fire and then the secret techniques, stretching and squeezing like a bellows as they list some of the ways to make love: “Lips/Fists/A mouthful of words.” Love and fire are the two essential human inventions and where we’re going, we’ll need both.

Love is patient but life is short. On Radical Romantics, Dreijer uncovers fresh anxiety about aging and the passage of time, if only because they feel they have so much love left to give: “What if I die with this song inside?” The album concludes with a mystery called “Bottom of the Ocean,” one for the whales, seven minutes of vocal drip-drops and scraping synths that unfold at the mournful pace of underwater footage of the Titanic. Previous Fever Ray albums set such meditative passages somewhere in the middle, so the bookend placement feels somehow deathly. Love is partially unknowable; could it be out of reach? Or, asks Lindbergh in Gift From the Sea, “Is it not possible that middle age can be looked upon as a period of second flowering, second growth, even a kind of second adolescence?” Here is love, vast as the ocean. Dreijer leaves us there, sinks down and out of sight as we come to rest in the ancestral womb of life, waiting to be born anew.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.