A version of this article originally appeared in the January 1997 issue of SPIN. On the 25th anniversary of Bradley Nowell’s death, we’re republishing the story here.

The smog blows east from the coast and there’s nothing to obscure this rooftop Long Beach vantage. You can see the endless strip of sandy shoreline—which established Long Beach as a tourist mecca—and the nearby oil refineries—which helped foot the tab. Facing away from the beach, there’s a hint of LBC, the ghettosphere where gangstas plot revenge and their next hard-core hit. Look straight down in all directions, though, and you spot patches of backyard green, little plots punctuated by sprinklers, crabgrass, hibachis, and Evinrudes. This is the flagstone cradle that rocked Sublime into early prominence.

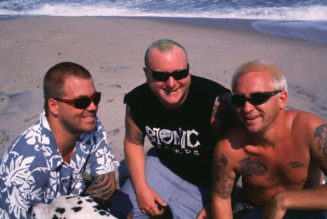

“We were, like, the band that everybody in the scene would show up for,” says drummer Floyd “Bud” Gaugh. He’s a soft-spoken, smooth-domed guy with a troubled face. “If you were having a party that night and you had us play, dude, there would be two other parties in the same neighborhood and everybody was going to be at the Sublime party.”

“Yeah, that was definitely my favorite time,” adds bassist Eric Wilson. “Because all the music was young.”

Wilson and Gaugh easily drift back to the days of backyard beer bombs. Back to when 300 to 400 kids squeezed onto some punk’s property and Sublime could pocket $250, big money at the time. Towering Samoans were party security and the cops left you alone until the noise curfew—after 10 P.M. their helicopters would hover just above tree level, the search-lights tracing psychedelic patterns through the leaves.

“The greatest bands I’d ever heard came from here,” says the gregarious Wilson, who looks a little like Randy Quaid, if Quaid had red biker-fuzz sideburns. “They only lived a short life; they were real major losers. They couldn’t handle it.” Wilson finishes his latest beer. “A lot of really great bands couldn’t stay together long enough.”

And then he lets out an amused snort. Nobody in the room even has to say it: The list of Long Beach coulda-beens has just got its first gold act. This backyard town saw the birth of Sublime, and then saw the band swallowed up by the drugs scored all too easily on the scene. Brad Nowell, Sublime’s 28-year-old singer, songwriter, and guitarist, died of a heroin overdose May 25, 1996, in a San Francisco hotel room. Two months after his death, the dexterous, optimistic Sublime came out. Instantly, the group had a hit on their hands. It was Sublime’s shining moment, except, of course, that by then Sublime had effectively ceased to exist.

According to one report, Gaugh had raided Nowell’s stash in San Francisco and shot up while the singer was out of the room. When he woke up hours later, Gaugh discovered that he’d been joined by Nowell, now lying stiffly on his bed. “I thought, ‘That was probably supposed to be me,’ ” Gaugh told a reporter in July. “The Grim Reaper saw him lying on his side, saw the tattoos, and thought, ‘That must be Bud.’ ” Now Gaugh says he doesn’t want to talk about that day.

Not long after Gaugh woke up in San Francisco, Nowell’s wife, Troy, received a call in Southern California from her sister-in-law, who was babysitting Brad and Troy’s 11-month-old son, Jakob. Come over now, Troy was told. Naturally, she wondered what was up. Troy got into her car and heard Nirvana playing on the radio. “And that’s when it hit me: It’s Brad,” she says.

The record Nowell left as his unintended testament, Sublime’s third, would be positively radical if it had come from Los Angeles, just 20 miles away. It mediates reggae, folk, and punk, makes them all constituent parts that serve a great songwriter’s vision. It might seem a daring experiment if it hadn’t so effortlessly sprung from a Long Beach surf scene that featured acoustic jams on the beach that naturally flowed from Wailers to Descendents classics, from egoless poise to omnivorous id-explosions. All of Sublime’s records are like beach-blanket headbangs, but Sublime succeeds not just on vibe but on songcraft. The bubbly, becalmed “What I Got” landed in the Top 40. Its best moments suggest not so much class-bonding ska as sun-baked lover’s rock; not so much guitar anthems as risk-it-all clamor unafraid of the glass wall.

Sublime converged back when its future band members were making sand castles at the beach, not bonfires. Gaugh and Wilson grew up across the alley from each other and met in a two-Big Wheel pileup. Wilson’s father was a former big-band drummer who reeked of pot and Binaca and taught Gaugh how to play drums. Wilson knew Nowell from around the sixth grade—Brad was a gifted kid without many friends who was bused to a magnet school. Years later, when Nowell was on a break from the University of California, Santa Cruz, where he was a finance major, Wilson introduced him to Gaugh and the three began jamming.

Sublime’s 1992 debut, 40 Oz. to Freedom, might have been forgotten, except two years later L.A. radio station KROQ began obsessively playing 40 Oz.‘s numb-nuts ska tune “Date Rape,” a song which the band had all but dropped from their set list by then. This infectious and loutish tune was attacked for turning a sensitive subject into a one-liner. But when it became an indie-rock hit—and helped put 40 Oz. on the Soundscan alternative chart for 70 straight weeks—the band shifted into high gear.

The follow-up, Robbin’ the Hood, was recorded in 1994, much of it in an earthquake-damaged house-cum-tweaker-pad with pirated electricity. It features a handful of finished tunes, including a duet with No Doubt’s Gwen Stefani. But mostly Robbin’ is artier and blurrier than the debut, hardly preparing you for Sublime’s Gregory Isaacs-style croonery, or the constancy of its craftsmanship. The songs never leave the group’s blue-collar damaged-boy milieu all that far behind, but Nowell becomes an artist here, opening up his hard edges to a broad range of experiences and observations.

“This would be an excellent place to be a sniper,” says Wilson, gesturing from his rooftop at the horizon. Wilson, Gaugh, and band manager Miguel (“just Miguel”) are drinking beers; at some point, the cat dish becomes an ashtray. I ask Wilson if he ever thinks of leaving the baggage of Long Beach. “No time soon,” he says. “This is as good as it gets,” adds Miguel.

Back in the apartment, a bong bubbles like a crocodile in a fun-house safari ride, as Wilson pulls down two photo albums. There are pictures of the trip the friends all took down to Costa Rica, where they surfed, plugged into whatever power source was on hand, and jammed on the beach. There are pictures of their dogs—this band loves their canines—and of the group on the first Warped Tour.

Beside the photo books is a flyer announcing an upcoming show by the Juice Bros., Wilson and Gaugh’s punk-rock side project. With Nowell’s death, the Juice Bros. is no goof; it’s a ticket straight back to the days of backyard glory.

“Hey punker,” the handwritten notice shouts, “See the band with a severe drug problem, and a hidden musical plan in which the audience doesn’t come first.”

Wilson puts down the bong, and picks up a guitar. Surfboards and a Beach Boys poster hang from the graffiti’d living room wall. Wilson hits a chord and ponders his musical future.

“There’s bands like Rancid—if they can make it, the Juice Bros. can,” he says, banging out another acoustic chord. “We’re just not sure we want to.”

In 1996, heroin became the Pete Best of rock’n’roll: a fifth wheel grinding in the background, an answer to a sick trivia question. Jonathan Melvoin, the Pete Best of Smashing Pumpkins, cashed in way too early; Art Alexakis of Everclear made millions finding a way to write off rehab as a work-related expense. At the same time Pantera’s singer Phil Anselmo was acknowledging his habit, the band’s guitar player Dimebag Darrell was quoted in a Del Taco press release saying, “Sometimes we just crack open a packet of the [hot] sauce and shoot it straight.” Stone Temple Pilots’ Scott Weiland and Depeche Mode’s David Gahan were arrested this year for drug possession. Bob Dole attacked Trainspotting, a movie he hadn’t even seen, for glamorizing drug use. It was political pandering, yet indisputably, to many heroin is hip, its aura of glamorous decay selling high fashion, its brand of risk one of the few transgressions popular culture was comfortable broaching this year. Heroin broke up bands, canceled tours. The industry convened a summit meeting. Everywhere, heroin has become a curse and a story; if grunge has peaked, its drug of choice has yet to saturate the market.

“Greater availability, higher quality, lower prices—I don’t know why there’s so much heroin around,” says the Butthole Surfers’ Paul Leary, who produced much of Sublime. “But it’s worse than it used to be.”

Early on, heroin became a part of the Sublime mystique. It was impossible to ignore on those tours when Nowell parked himself on the edge of the stage, the others noodling gamely while he was patently unable to make it through a song, let alone a set. Rumors of overdose abounded. “Yeah, I think we’ve all been dead once or twice,” says Gaugh. Nowell would sometimes even steal the band’s equipment the day of a gig and pawn it for drug money, knowing full well that Miguel would get everything back for that night’s show. (From Sublime’s “Pawn Shop”: “What has been sold is not strictly made of stone / Please remember it’s flesh and bone.”)

But there was far more to Nowell than that. He was a well-read history buff who’d stay up all night talking with strangers. He had an unprogrammatic curiosity that cut through bullshit, and a kind of endearing shaggy-dog naiveté about many parts of life, including drugs.

When he first started using heroin, “it seemed to me that he didn’t know that much about it,” says Troy Nowell. “He was so ready to tell me that he was on it, and he wasn’t ashamed that his audience knew if he was in the bathroom doing it.”

One sun-dappled afternoon, not long after Stone Temple Pilots have announced Scott Weiland’s release from rehab and plans for a lucrative fall tour, Nowell’s widow sits in the backyard of an Orange County coffeehouse. “What I’d really like to do now is move up to Santa Cruz. It was Brad’s favoritest place, and it’s just a beautiful place to raise a child,” she says.

“I just feel I need a new beginning. A lot of times I drive through Long Beach and I’ll remember bad things… There’s times I’ll drive down a street and remember, ‘This is where Brad copped dope.’ My fondest memories with Brad are not in Long Beach.”

Her son, Jakob, has wandered off, and her father-in-law rises to get him. Since Nowell’s death, Troy has talked often with the widow of Blind Melon’s Shannon Hoon. These days, Troy is taking college courses, aiming to become a drug counselor.

“I used to always envy that Brad had gone to school; I always thought I couldn’t, there’s no way I could go.

“I used to do things to make him proud, so I get mad that he’s not here and I can’t show off when I get a B on a test.”

Nowell would point to old-timer William Burroughs as someone who knew how to hold his drugs; mention Hoon, and Nowell would say the guy was stupid, somehow weak—even when Nowell was shifting in his pants from the five clonodine patches he’d slapped on to help him kick, he couldn’t give up the illusion that heroin was indelibly cool.

“He got this elitist attitude because he was a junkie,” says Troy. “He always used to say, ‘You guys don’t understand, because you don’t do heroin.’

“A lot of junkies are like that. They think they’re doing the most hard-core thing, sticking needles in their arm. We could say anything—’We understand what you’re going through’—but we really don’t, and they know that. They like that.”

Surfers seek out extremes. Not because we reward them, but for purely personal reasons. Nowell was a passionate surfer; sometimes he and his bandmates would sail out to the Channel Islands to surf the isolated beaches. In his mind, the thrill of drugs and surf were connected. On his arm, covering up the vein, stretched a blue tattoo of a monster breaker. He’d slip the needle in, and then he’d paddle out.

“That’s it, I quit,” declares Wilson. There had been beers and bones in the afternoon, then a 40-ounce on the way over to the restaurant. Captain Jack’s—owned by Chicago Bulls bench-warmer Jack Haley—is one more seafood joint on the strip of surf towns just south of Long Beach. “Did you see?” Wilson asks. “Captain Jack’s brother Tim said ‘Hi, Sublime’ at the door!”

There are mai tais before dinner and then several bottles of wine with the food, until somebody hits the antigravity switch and glasses began floating off the table and it is suddenly time to leave.

We drop off Gaugh in Huntington Beach. Driving back to Wilson’s apartment, we stop at a 7-Eleven so Miguel can buy more beer. Getting into the car, apropos of nothing and everything, Miguel blurts it out.

“It was an enlarged heart.” We digest that for a minute, and then he continues. “That’s what his condition was. He had it for a year, and he wouldn’t tell anybody. I didn’t know about it. Did you?” he asks Wilson.

“Nope. He didn’t tell me.”

“His dad didn’t even know,” says Miguel. We pass the place where Robbin’ the Hood was recorded, then drive through the fog rolling off the waves, and finally Sublime are home.