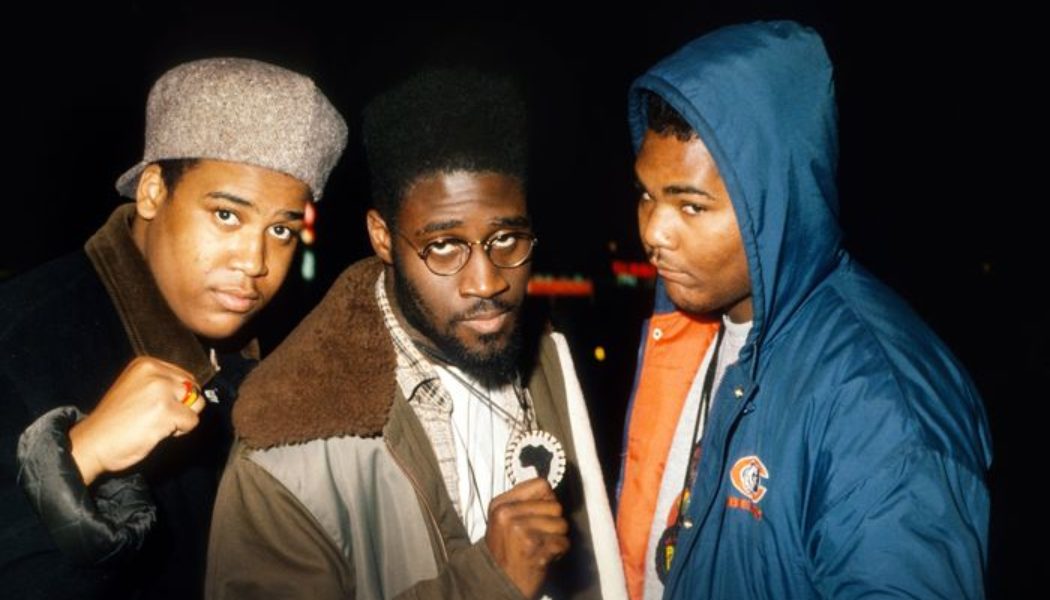

Three is the magic number: Trugoy, Posdnuos, and Maseo in 1989. Photo: Gie Knaeps/Getty Images

No one who fell in love with De La Soul in the ’80s and ’90s could have predicted that the music would eventually slip into the Phantom Zone, where the only available versions were bootlegs. Or that, on the cusp of the long-delayed release of the trio’s full catalogue to streaming services on Friday after years of label woes, we would be mourning David Jolicoeur, the New York hip-hop legend who literally put the “De La” in De La Soul. The group’s absence from Spotify and its ilk due to a combination of rights transfers and corporate neglect flew in the face of what we understood to be the unspoken laws governing the business: You make great and impactful music, cultivate an audience and hold its interest over the years, and somebody will keep your shit in circulation, if only because there’s money to be made. Fans of the Native Tongues collective were already familiar with the jig, though. “Industry rule No. 4,080,” Q-Tip famously rapped in Tribe’s “Check the Rhime.” “Record-company people are shady.” But it’s bigger than that. Withholding a body of work recognized by the Library of Congress was an indictment of the structural integrity of the streaming ecosystem. If 3 Feet High and Rising could go missing, anything could.

De La Soul — childhood friends Kelvin “Posdnuos” Mercer, Dave “Trugoy the Dove” Jolicoeur, and Vincent “Maseo” Mason Jr. — got their start in the mid-’80s, producing homemade pause tapes with their families’ record collections. When a demo of what would later become “Plug Tunin’ (Last Chance to Comprehend)” made its way to Prince Paul, a familiar face from school making a name for himself in the rap group Stetsasonic, he and his bandmate Daddy-O brought De La to their label Tommy Boy Records. Paul was hungry for greater responsibilities than Stetsa had space for so he began fielding unusual ideas about source material from the Long Island trio, fleshing their pitches out on professional Akai racks and lo-fi Casio sampling keyboards. The freewheeling feeling of their eventual debut, 1989’s 3 Feet High and Rising, is a testament to the rapidly expanding musical tastes of all parties involved but also to the self-effacing humor that would color the next few albums.

One of the many terrible ironies about the absence of De La Soul’s catalogue from the streaming revolution is the way the early records are expeditions into the history of recorded music. Referencing the psychedelic spirit of the late ’60s in its music and iconography, 3 Feet High declared a “D.A.I.S.Y. Age,” as the Plugs lampooned emerging tropes in rap, laughing at everyone’s preoccupations with brand loyalty and materialism. There was youthful enthusiasm in the group’s collision of psych-rock, funk, soul, and children’s music, in figuring out how to get both Johnny Cash and Eddie Murphy’s voices into a chop of a Schoolhouse Rock jam, in dropping references to Disney’s Snow White in a song built around Funkadelic’s salacious, celebratory “(Not Just) Knee Deep.” 3 Feet, along with its contemporaries in the field of late-’80s rap classics (Beastie Boys’ Paul’s Boutique, Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back), made sampling feel like a burgeoning new science as they rearranged bits of old sound and wisdom into new forms and ideas.

1991’s De La Soul Is Dead upped the ante by poking fun at themselves while broadening their lyrical and musical palettes. “Pease Porridge” showcases tighter rhyme skills over samples of nursery rhymes and tap-dance breaks; on “Johnny’s Dead,” Dave delivered a tongue-in-cheek murder ballad in Jimi Hendrix’s vocal cadence. “Fanatic of the B Word” staged a clever bait and switch, dropping a title that primes the listener for the degradation of women but using verses that are only interested in juggling syllables and words that start with the second letter of the alphabet. The ironic hip-house song is a riot; the disco tune is timeless.

Uninterested in revisiting the psych-rap sound they perfected, the group used their third album, Buhloone Mindstate, to plug into the jazz rap working wonders for De La’s younger compatriots in Tribe, packing out the album with legendary players such as saxophonist Maceo Parker and trombonist Fred Wesley. But the maturing sound and mind-set didn’t sell as well as the affable schoolkid dreams of the first album, in spite of gems like the alternatingly grisly and giddy “3 Days Later“ or the wizened, reflective “I Am I Be.” Buhloone displays almost combative resistance to what we had come to expect from De La, the psychedelic sound sculptures underneath introspective verses and the crew affiliation that made the first two albums feel like integral points in a tight attack formation of rap geniuses. 1996’s Stakes Is High worked out a more statesmanlike though no less abrasive posturing. De La was a bridge between generations, one of the points around which the electronic aesthetic that ’80s rap had inherited from the earliest samplers and drum machines had blossomed into the kaleidoscope of sounds the genre would pull from in the ’90s.

The three studio albums they released in the aughts comprise a second career arc in which De La Soul learned how much magic they could pull off with admirers at both indies and majors. 2000’s Art Official Intelligence: Mosaic Thump and 2001’s AOI: Bionix, installments in a planned trilogy, fluctuated in style (and sometimes quality), dabbling in slick, catchy songs, personal narratives, lyrical workouts, and love letters to hip-hop’s golden age. The commercial sounds of songs like “All Good?” with Chaka Khan threw longtime fans for a loop. But inside the group, AOI had been floated as a bit of a plot to speed up the process of getting off Tommy Boy to pursue other options.

The move was fortuitous: In 2002, Tommy Boy founder Tom Silverman ended a decades-long partnership with Warner Music Group, ceding valuable catalogues and publishing to the major and dispersing acts like Everlast, Sneaker Pimps, and Prince Paul and fellow DJ-producer Dan the Automator’s Handsome Boy Modeling School to the winds. De La pumped the brakes on the third AOI album and linked with indie hip-hop luminaries Madlib, Dilla, and Supa Dave West while assembling verses and hooks from a versatile cast including dancehall star Sean Paul, Bad Boy R&B vocalist Carl Thomas, Common, and Flavor Flav. 2004’s The Grind Date revels in a newfound freedom across the Dilla production “Verbal Clap,” “He Comes” with Ghostface, and “Rock Co.Kane Flow” with MF Doom.

Photo: Tristan Fewings/Getty Images

While De La Soul was calling their own shots, the back catalogue gathered dust in Warner’s possession, where the care in clearing the samples that 3 Feet High and Rising and De La Soul Is Dead required was again neglected. De La and Prince Paul blamed Tommy Boy as their classics missed out on streaming splits. They’d sent the label a list of source material for clearance purposes that never got the thorough follow-through it deserved. The label didn’t seem to understand that it had a masterwork on its hands whose success under a Warner umbrella was certain to come to the attention of a writer or two who didn’t like being repurposed in a rap song. In the roiling culture wars of the ’80s and early ’90s, rap had come under such a fine microscope that rappers got rebuffed by members of Congress and absurdly, the president. They didn’t know that 1989 would be the beginning of a succession of tense court proceedings that altered the very sound of rap as copyright infringement suits against De La and, later, Biz Markie grounded the high-flying sampling feats that defined the era. Letting the catalogue rot as rap music surged in popularity in the aughts and as listeners flocked to streaming services in the early 2010s is Warner’s cross to bear. Tommy Boy’s offer to give the group 10 percent of streaming revenue after it reacquired the catalogue in 2014 was an insult.

De La’s luck cut two ways, though: They arrived in the heat of predatory deals and wars over royalties, and they were also at ground zero for the ascendance of Prince Paul and J. Dilla. Their concoction of cynicism and earnestness and their musical and lyrical conventions would wash over wave after wave of rap stars. By the end of the ’90s, De La Soul Is Dead’s 73-minute explosion of long songs and hilarious skits had become the preferred format for a major-label hip-hop album. In the aughts, Ye brought Native Tongues sensibilities to Roc-A-Fella Records, and Damon Albarn’s appreciation for the group yielded Gorillaz’s “Feel Good Inc.,” the international hit that earned the trio their only Grammy. Odd Future’s war with blogs and mainstream artists in the 2010s showed shades of De La’s repeated bouts of poking the bear. It was a travesty for the group to have spent that decade watching the rights of their classics bouncing from owner to owner, especially in the last years of Jolicoeur’s life (though the Kickstarter success of 2016’s And the Anonymous Nobody… went to show that De La Soul had maintained a motivated fan base through the years). But then it’s not a very unusual story: Taylor Swift is rerecording her entire back catalogue because she doesn’t own her masters.

The history of the music business is littered with tales of eager young artists being pushed into deals that ask for outsize fractions of the ownership of their work, people who “try to snatch the credit but can’t claim the card.” As we revisit De La Soul’s catalogue, tracing Pos, Dave, and Maseo’s arduous trek through the major-label rap machine, it is important to recognize that there’s no way to stop something like this from happening again. No song we love is guaranteed to remain easily available to us no matter how seminal, recognized, and successful it is in the moment. Great music is rendered bafflingly scarce all the time. It’s as easy as an indie shuttering because of overwhelming rent prices or a notable rap label offloading jewels in a pivot to dance music. And if that’s the lay of the land at the labels, then the streaming services that partner with them are just as subject to abrupt, unexpected, and unwanted changes. As fans and patrons, it behooves us to remain mindful of this reality, supportive of talent, critical of suits who treat valuable cultural artifacts like pieces in a private collection nobody else gets to see, and wary of a business structure that revolves around the bartering of the work of producers and songwriters among parties who did not and cannot write or produce anything. Our icons and our culture and history deserve much more.

The nickname the trio took a liking to after “Plug Tunin’”

“Everything started to decline a little bit, and as the guys got older, they were kind of growing apart,” Prince Paul told Complex in 2011. “We started our first record as teenagers, and now things were getting real.”