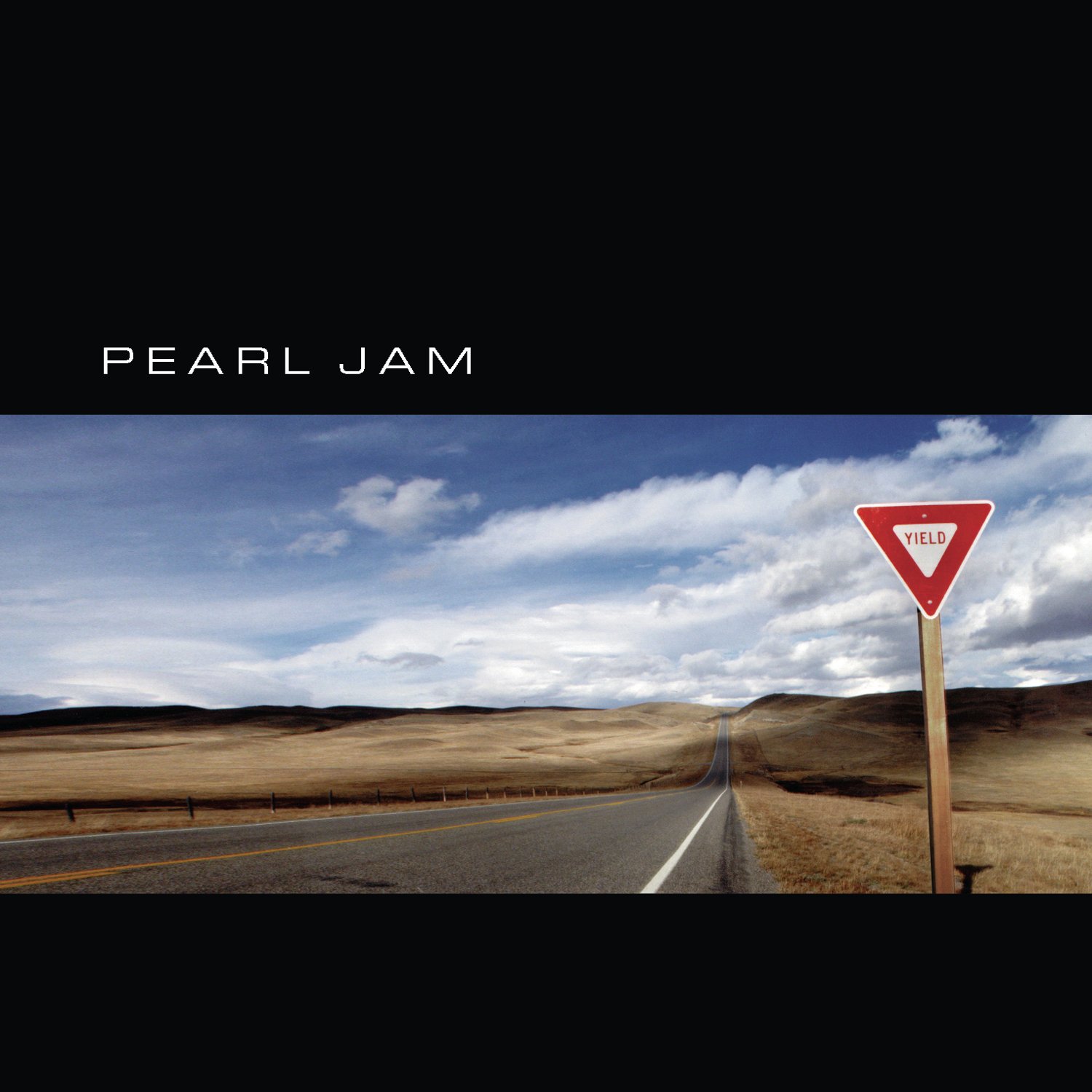

This article originally appeared in the March 1998 issue of SPIN.

Angels are God’s designated hitters. They’re represented in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, among many other religions; they pretty much show up anyplace people put out a punch bowl and a turntable. Messengers of supreme beings, keepers of the gate, angels are the ones who feel the full weight of responsibility. “Just call me an angel,” Eddie Vedder seems to groan over the fadeout of a new song on Pearl Jam‘s fifth album. And he’s got plenty of company. Angels are all over Yield: “Given to Fly” is about a seraph who breaks free; there are references to angels in the dirt; and “Do the Evolution” even features a choir singing hallelujahs.

Angels have become Vedder’s nervy way of talking about himself these days—he’s a message-bringer for the masses, yet someone desperately in need of a good word himself. On the one hand, he has his responsibilities as ‘keeper of the flame.” On the other, he shouts *I’m not trying to make a difference” like a man who really wants out. He’s dancing on a pinhead between these polarities, yet on Yield he’s never sounded more at home, wrestling with the contradictions.

On last year’s No Code, Vedder shot out the lights, duct-taped his mouth, and hid in plain sight. This was one of the more famous people in pop culture staging an interior monologue for public consumption; it sold diddly. The revelation of Yield begins with Vedder’s effort to communicate again. The album keeps unfurling out and out like a time-lapse loop of a garden blooming. No Code had its trancey Eastern flourishes, but on Yield, Vedder’s 1995 duet with Sufi mystic Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan really takes root. The late Pakistani singer erected great swooning edifices that seemed to sweep all sound away and transport you to a tranquillity base that was flat to the horizon line. Khan’s music directed you to a spiritual savanna, and that’s very much where Vedder wants to go. He sings about a God who’s used to our noise—while everywhere Pearl Jam rocks harder than they have since 1993’s Vs. For him, enlightenment has to come “like a fist to the jaw.” The jangly ballad “Wishlist” frames Vedder’s intent—he prays one moment to connect with other people, the next to flee to the far side of the sun. In either case, the revelation will not be televised by Spike Jonze; it will not come like a goddamned Ticketmastered rock festival. Transcendence and oblivion are fraternal twins to Vedder. He’s looking for a guardian angel to coldcock him into another place, because if you’re gonna see stars, let’s see stars.

“I wish I was a neutron bomb / For once I could go off,” Vedder quavers on “Wishlist,” and you can sense that he’s sorted out the difference between fantasizing about going off and actually living it out. “In Hiding” describes a shut-in’s hallucinations—they could be heavenly visions, or a mind slipping through the floorboards. Uniformly the words are cracked and vague. Halfway through the album, when a helium-high voice chirps “We’re all crazy and warped,” it’s not telling us something we don’t already know. But there’s nothing vague about the way Vedder sings, or about the way the band’s acoustic and electric guitars play off each other, or about the way Jack Irons kicks tunnels with his drum kit. In the past, Pearl Jam’s songwriting and arrangements could be rather pedestrian, but everything on Yield, every piece of sound—from bassoons to feedback squeals to acoustic strums—means something.

“I’m like an opening band for the sun,” Vedder sings on “Push Me, Pull Me.” It’s a comic way of referring to heavenly heralds, and you can hear a certain self-seriousness in there, but it’s also a thoughtful way of dealing with the place where Vedder currently finds himself. He sees the sea of Bics, and he knows that it’s what he’s worked for—a reflection of his own light. But he still wants a light that will shine on him, and whether it’s going to be a bolt of transcendence or a big bang, he’s not predicting. All you know from Yield is the imminence of impact.

If you read Commodify Your Dissent, the recent collection of essays from consumer-baiting fanzine The Baffler, you’ll be told a dozen different ways why Pearl Jam are corporate-rock Antichrists, siphoning off the texture of punk rock and marketing it to the masses. But in 1998, “Spot the Sellout” seems like a geekier party game than “Pull My Finger.” And if the straitjacket didn’t fit Pearl Jam back in the grunge era, it’s patently absurd now. Such put-downs don’t recognize a band that’s never stood in place, that’s always wrestled with its responsibilities, only to land smack in the middle of an era when bands brag they don’t have any. Part touchstone, part pariah, Pearl Jam have tried arty gestures; they’ve ostentatiously declined to rock; and now they’ve come back with an album full of gracefully ambivalent anthems. All commodities should be this unstable, and have this much blood pumping through them.

Tagged: 1990s, Archives, pearl jam