In a world of fleeting fashion trends and escalating production costs, the fashion luxury industry finds itself at a crossroads. Second-hand fashion luxury represents both an opportunity and a threat for traditional brands. Could the true essence of luxury lie in the timeless allure of high-quality, limited-edition pieces from decades past? If so, how should traditional brands adapt?

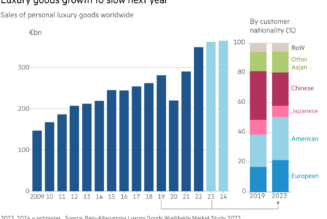

The Age of Shrinkflation and Threats to Scarcity in a Globalised Luxury Industry

Once upon a time, acquiring a luxury item often required a pilgrimage to a specific city, where local brands cultivated exclusivity and craftsmanship, defining qualities of luxury. Long before the digital boom and the rise of luxury conglomerates, each market had its unique set of offerings, heightening the sense of rarity and personalization.

Fast forward to today, and one finds near-identical luxury products, ubiquitously available around the globe, in shopping malls and department stores with standardised offerings. Luxury fashion conglomerates such as LVMH and Kering dominate the industry but have to manage the delicate balancing act of maintaining profit margins while upholding the artisanal quality that originally defined luxury. To do so, raising prices, also a vehicle of exclusivity, is a strategy of choice. So are optimising production costs by creating economies of scales and reducing complex finishing touches on garments, which were once the pride of the industry. A more radical way to maintain margins is to reduce the quality of raw materials altogether.

Another issue looms for major players: the abundance of high quality second-hand items challenges the carefully orchestrated scarcity of luxury items. Add to this growing pressures for the industry to be leading the way on ESG and the path for growth becomes complex. According to Olivier Nicolay, who served for more than two decades as the president of the UK, Canada and LATAM region at Chanel: ‘Today, the volume of products available on the second-hand market is potentially larger than the production capacity of most major brands. Because these brands are already using most of the traditional recipes for growth, they will not be able to grow sales volume and reach their ESG goals at the same time without reinventing themselves.’

A Paradigm Shift led by the Youth: The Rise of Vintage Enthusiasm

Gone are the days when donning vintage was met with societal scepticism. The narrative has, in fact, done a 180-degree turn. Today’s younger consumers, led by the eco-conscious Gen Z, perceive vintage as an ultimate expression of individuality and sustainable luxury. The act of unearthing a timeless piece from a vintage shop has transformed into a treasure-hunting social event for teenagers in quest of rare items.

Not just a trend but an emerging category, second-hand luxury is increasingly serving as an initiating rite for aspiring luxury consumers. In an age where even entry-level luxury accessories can be financially prohibitive for most, vintage items offer a more accessible option.

Moreover, vintage luxury fashion may soon align with other high-value categories like art and furniture, elevating these rare, high-quality items to investment class status. Pieces from bygone decades, produced in far smaller quantities and often region-specific, now command a unique allure. While the price tag of vintage luxury at auction is yet to match that of other categories, the potential is there.

The Quest for the Perfect Business Model

Despite the growing enthusiasm for second-hand fashion luxury, the sector still faces challenges, Major players on the resale market, such as TheRealReal or Poshmark are struggling to find a durable path to profitability. Issues include quality inventory and the carbon footprint associated with global shipping. An item may travel a considerable distance from its original owner to an authentication centre, before being shipped to a new owner. Authenticity, particularly in categories like watches, adds another layer of complexity.

Consumer education to buying vintage luxury fashion is also key – especially when it comes to shaping consumer expectations around second-hand luxury. Major platforms are already introducing grading systems to clarify the condition of items, from “new with tags” to “fair condition.” This not only enhances consumer confidence but also establishes a foundation for market growth, offering items to meet the budget of a wider pool of aspiring luxury consumers.

For major luxury brands, this could mean a momentum to seize to enter the resale market. This may, according to Nicolay, lead to a deep transformation of the whole luxury industry business models. ‘This could also pose a particular challenge to traditional department stores, which will need to find a way to remain relevant in this evolving luxury landscape, where platforms and brands may seize the lion share of the market.’

The Implications for Legacy Luxury Brands

When it comes to traditional luxury companies, embracing the circular economy represents a dilemma. Margins in this category are considerably lower, and selling an item that may not be in pristine condition represents a departure from the traditional image of perfection associated with luxury. Naturally, some consumers may prefer to buy a cheaper alternative to a new item. Finally, for certain categories such as designer handbags, this could de facto increase the supply of items to purchase and reduce perceived exclusivity. Some brands, such as Saint Laurent, have experimented with selling vintage and curated items – in the case of Saint Laurent, t-shirts from iconic rock bands – although not pieces from the brand itself.

With the circular luxury market gaining traction, traditional luxury companies are faced with existential questions surrounding supply chain control—even for second-hand items. If they wish to maintain their cachet, monitoring the second-hand market could become as crucial as overseeing their primary offerings.

As Nicolay argues, ‘luxury brands will soon face a new equation when it comes to second-hand. Product traceability, combined with growing ESG obligations, a need to control the distribution of items – new and old – and reaching growth objectives will make secondhand a more appealing option.’

‘Legacy luxury brands will also be better placed than major second-hand platforms as they have local expertise and adequate supporting logistics in each of their boutiques to handle supply and demand without generating the carbon footprint of typical resale platforms.’

As the luxury landscape transforms, one thing is certain: Circular luxury fashion is not just a passing fad—it’s a seismic shift that could redefine what true luxury means for the modern consumer, and force existing players to adapt to a new reality.