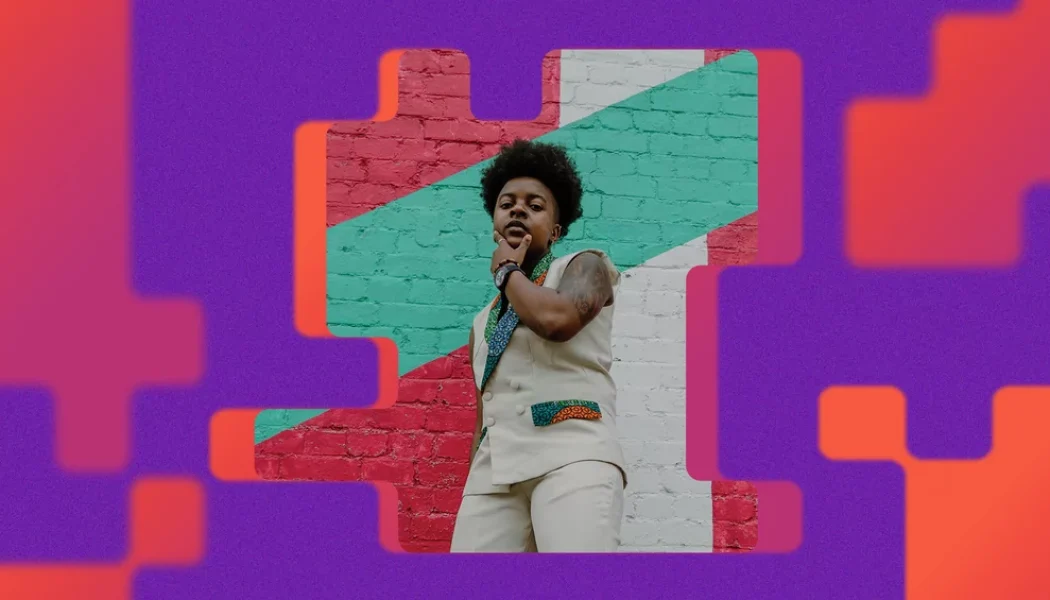

There has been this Eurocentric narrative in recent years about ‘discovering’ African electronic music, which is problematic for a number of reasons. I’m curious what your perspective was coming from Malawi and then spending time in other African nations and then the Global North for the first time. Were there any impacts on your identity or in your music related to interacting with the broader Black diaspora?

“Definitely. Malawi is a small, Black-majority country. We’re small in the sense that our culture was never really the dominant culture on television when I was growing up. Popular culture was American music, American media. Then South Africa started coming up, especially in the post-Apartheid era. I started seeing a lot more music flowing freely from there. We were getting Brenda Fassie cassettes, and Black Coffee started making mixes. My own sound was just based on whatever cassette was brought in. The internet was still new so there wasn’t that much freedom, but I was able to start to explore the sound of other African countries.

“In terms of my own identity, as an adult I became more aware of my country’s positionality, colonisation, post-colonisation and what Apartheid had meant in South Africa. In a sense, it became like a politicisation of music for me, realising just how much is held in sound. Now as African music is taking centre stage and there is this intense commercialisation coming in, I have this sense of wanting to protect it and make sure it’s done right, without losing that space of what music means, especially for the global diaspora. For people on the continent, music has always been this active space where people were liberated through music; it was a form of organising and bringing people together.”

Speaking of organising and liberating, we’d love to ask about your organisation, Tiwale. What spurred you into starting it 10 years ago?

“It was an emergency, something that had to be done. A really close friend of mine was forced into child marriage when we were around 15. She stopped showing up to school, then I saw her six months later at a market, and she said, ‘My parents found me someone to marry. I’m moving out of the country. He’s going to support my family so that my brother gets the best education’. She’s someone who was so gifted in science subjects and would help me with the schoolwork I struggled with. I was very surprised, but I wasn’t shocked. That was 2009, and child marriage was only criminalized in Malawi in 2018.

“I became passionate about helping push the government to criminalize child marriage, and also looking at the factors behind why it was happening. A lot of it was this belief that if you educate your male child they will support the family, and when your female child gets married into another family then they become her family. Also, the government charges high fees for secondary education. Then when you look at primary education statistically, we had 114% attendance, where adults will go back to school again because it’s free. But at secondary level, you’d see a drop to 33%. Only 6% of secondary school-aged girls attended school. In tertiary education it’s less than 0.01% of girls. So Tiwale considers these economic factors and the incentives we can create to break this cycle, and encourage mothers to continue to invest in and educate their daughters.

“Some of the first programmes were focused on microfinancing and giving out business loans to women, then we also looked at educational scholarships and vocational skills training. We do things like sewing classes, STEM education, digital literacy and getting folks to do technical degrees and learn coding. For me personally, as someone very passionate about music, I know that less than 2% of producers in the world identify as women. So we started looking at that in our programming as well, and started DJ and music production workshops. When you attend the workshops and participate for six months to a year, we connect you with internships with radio stations and event spaces. It’s been great, we’ve seen some of the graduates now DJing on a weekly basis, and we have people playing at festivals. But the whole essence is really just to break some toxic socio-economic-cultural cycles.”

To finish, let’s loop back to the first question, thinking about your music. Where does your own music fit in alongside this very demanding work?

“I’ve definitely struggled between my job, Tiwale and music. But each one feeds the other in different ways. My music is very much influenced by some of the stories that I hear. Sometimes, especially when it comes to organising on the continent, there’s a sense of dehumanisation where, yeah, we need the basics: food, water, shelter. But there is so much more. We also need mental health, we also need care. We need hugs. I feel all that being in these different spaces, and I want my music to reflect and encompass all of it, all of that learning, all of that growth.”

More in DJ Mag’s Black Artist Database label feature series…

A new home: Black Artist Database on their label debut, ‘Synergy’

Pushing the envelope: Afrodeutsche & rRoxymore in conversation

Works in progress: Amaliah and NIKS in conversation

A matter of faith: Lyric Hood and DJ Holographic in conversation