Outside its borders, the music of the Central African Republic (CAR) is little known. The country is most often perceived through the distorting prism of an international press that relays the history of its conflicts or the current horrors of the mercenaries of the Russian group Wagner. But in the midst of political and humanitarian tragedies, war also has other victims who suffer in silence: musicians and music lovers. I now count myself among the latter, since I dove into the ocean of the web to fish out a few pearls that testify to the creativity of the former. This is my chance to make a mix of them, and to share with PAM readers some of the treasures I’ve found, and the winding path that led me to them.

When I decided to take a closer look at the music of the Central African Republic, I quickly came up against a dearth of information, as physical supports are rare beyond a few reissues and compilations such as those in Radio France’s Ocora collection, which collected music from the oral tradition in the 1970s (see here and here).

Wanting instead to take the pulse of local pop, I stumbled in my quest on these ethnographic recordings of traditional music featuring xylophones, harps and sanza (thumb piano, used here to accompany “thinking songs”). Particular attention is paid to polyphonies, such as the astonishing ones played on trumpets by members of the Banda-Linda tribe, requiring one musician per note, to be discovered here or there; or the vocal polyphonies of the Aka pygmies.

Fascinated by this heritage, I’m no less curious about what’s going on outside the equatorial forest: so I turn to YouTube to access the country’s urban and popular music. Nourished by this research, which allowed me to scratch the tip of a cast-iron iceberg, I put together a mix in the pandemic decline of 2022, which strives to paint a broad portrait of contemporary music from the CAR, discovered through clicks. A varied and prodigious music, a living and surviving music, played in the face of misery and death, a music for all its worth. Let’s take a closer look at some of the songs in this selection, each of which offers a glimpse into the country’s history.

The 60s: post-independence euphoria

The first local recordings flourished in the 50s, and were imbued with the melodies of the neighboring Congos. The capitals of Leopoldville and Brazzaville were the destination of many Central African artists, as the network of radio stations and studios was better developed there, and a common Bantu culture conveyed similar musical sensibilities. Songwriters such as the pioneering Prosper Mayélé got their start there, covering popular Cuban and Ghanaian highlife tunes, as did the famous pioneering guitarist Jimmy “The Hawaiian” Zakari, who formed the arpeggiated style of Congolese legend Franco Luambo Makiadi. These two pioneers would later return home to put their Congolese experience to good use in the development of the country’s music.

After independence from France in August 1960, the decade saw, under the aegis of the first president David Dacko, the emergence of the first amateur orchestras – made up largely of teachers (Vibro Mayos, Centrafrican Jazz) or soldiers (Commando Jazz) – who competed in private parties and bar-dances with evocative names: “Ciel d’Afrique”, “Dragon Rouge”… In a scene dominated by covers of Congolese stars such as Kabasele and Rochereau, a national music scene began to take shape. The two pioneers Prosper Mayélé and Jimmy “The Hawaïan” Zakari played a key role in this.

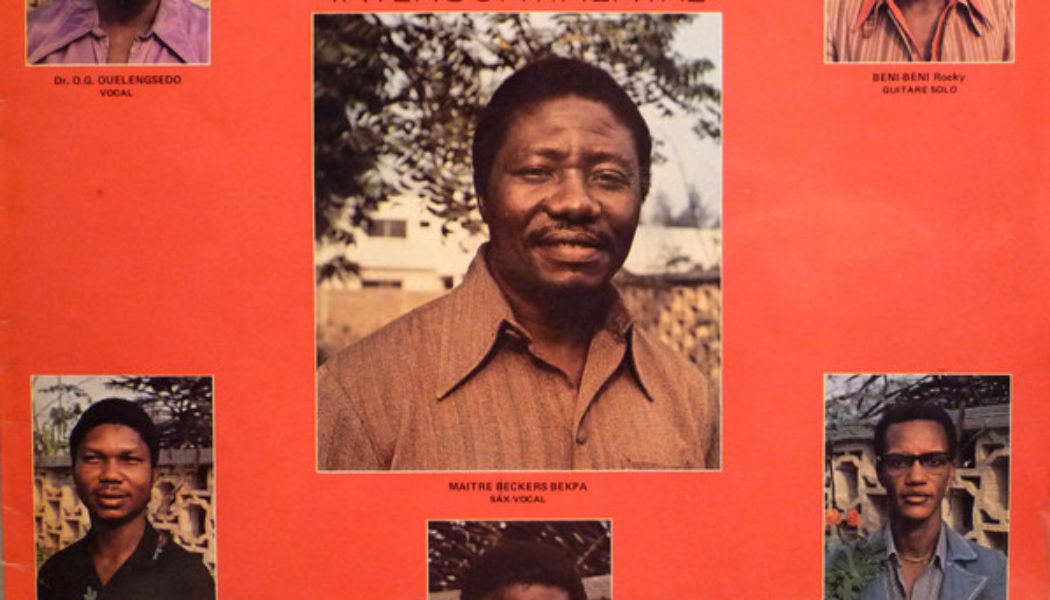

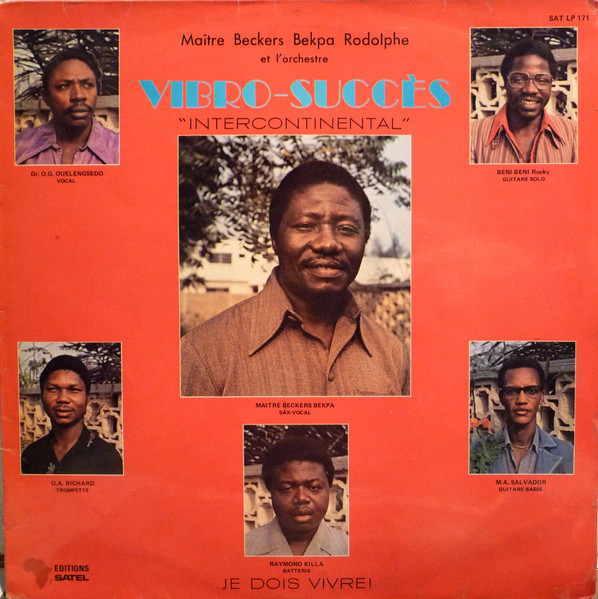

Led by the brilliant saxophonist Bekpa “Beckers”, the Vibro Succès orchestra represented the young Central African nation at the 1974 Festival de la Francophonie in Quebec, where it won a gold medal – one of the few events to mark international recognition of the country’s music. The track “Dounia” features the striking beauty of male choirs singing in unison, reminiscent of the style of their Congolese cousins. Velvety vocals caress a bouncing orchestra, twirling guitars in the background and a saxophone that embraces the soul with a few solos… “oh, pardon chéri!“

The Bokassa era: from hope to hell

Jean-Bédel Bokassa took power in 1965, ousting President Dacko who, according to his French “protectors”, had had the bad taste to turn to Communist China. The ex-Chief of Staff – who had not yet turned megalomaniac – got off to a promising start, and his “Bokassa operations” of nationalization initially turned the country’s economy around. The 70s were a flourishing decade in the capital, then known as “Bangui la Coquette”, where dance halls multiplied.

It wasn’t until the 70s that the status of professional musicians developed in CAR. Leading groups of the time, such as Formidable Musiki led by Thierry Serge Darlan aka “Yezo”, encouraged a new generation to embark on a career. The tutelary figure of Yezo left a lasting mark on the diaspora, including the new generation who still pay tribute to him today.

Legend has it that the orchestra was created in 1974 thanks to the patronage of the director of Bangui’s Safari Hôtel, with the aim of creating an “international variety” band that would do the country proud. The experience gained by Yezo during his initiatory trips to Africa – such as Abidjan, where he had joined the Radio-Télévision Ivoirienne orchestra under the direction of a certain Manu Dibango – had made him realize that the Central African Republic was brimming with talent to be showcased. Originally simply called Muziki, this “orchestra for young people aged 7 to 77” earned its “formidable” epithet like a stripe thanks to the praise of a dazzled local public, who soon demanded a repertoire sung in Sango, the national language.

“Wo! Woulouwo! There’s something mischievous about this sentence from Formidable Musiki’s hit “Ti laso a ounzi awe“, with its highly effective guitar riff and its singers’ infectious enthusiasm. It never fails to set dancefloors alight at the Berlin “African Beats & Pieces” parties where I officiate. We smile at the incongruous arrival in the song of an advertisement for a webmaster in the style of a Congolese libanga: “La nouvelle formule informatique ww.fr en direct de Lyon“.

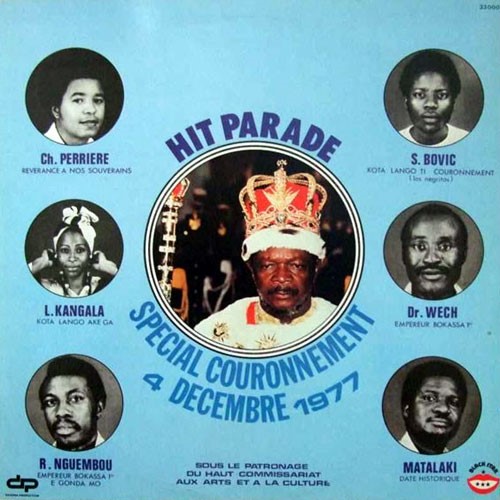

The situation worsened at the end of the 70s for a people in the hands of a Bokassa who had turned dictator and crowned himself emperor on the model of his idol Napoleon, while the economy sank and food insecurity resurfaced. Faced with this situation, many intellectuals and artists fled into exile in a sinister end-of-reign atmosphere. In 1979, Bokassa was deposed by the French army, who reinstalled his first cousin David Dacko as president. He was ousted two years later by André Kolingba’s coup d’état.

Back to basics at the end of the millennium

The early ’80s saw a revival of traditional-modern music: a number of groups called “Zokela” popularized the syncopated trance dance known as “danse des chenilles” (caterpillar dance), known as Montè Nguènè (“pleasure” in the Mbati language) and derived from a tradition of the Ngbaka pygmies of the Lobaye region. This dusting off, necessary to “revive the soul of the country”, is achieved by replacing the n’gombi harp with the electric guitar and the drums with the drum kit. Montè Nguènè has thus moved beyond rural and ritual ceremonies to urban dance floors, carrying the banner of typically Central African festive music.

This desire to promote and preserve a common cultural heritage, a source of pride and cohesion, would take on its full meaning a few years later, in the context of the instability and conflicts that would fracture the nation: “My greatest concern is to bring Montè Nguènè up to the same level as Congolese rumba, which has been listed as an intangible cultural heritage of humanity by UNESCO. We Central Africans also need to promote our musical identity. We have to work hard to make Montè Nguènè part of this heritage“, declared musician and peace activist Losseba Ngoutiwa on Central African radio station Ndeke Luka in 2021.

In the 90s, new artists such as the groups Ndaï Ndaï – a name derived from a popular Sango expression meaning “ecstasy” – and Abakinlin from Bangassou continued this work of musical cross-fertilization and return to the roots of the country’s different ethnic musics. They advocate the use of traditional instruments to convey ancestral messages.

These songs captivate with the depth of their polyrhythms, the bewildering complexity of their polyphonic melodies and the invocation of nature through the insertion or imitation of birdsong. “Oh éh, I’m in over my head, I’m 100% pygmy, I live in the forest among the trees, I need my husband,” laments Francis Gon, about whom absolutely no information can be found online, as is all too often the case in the quest for texts and contexts for Central African music.

The scourge of instability: from coups d’état to civil wars

Although the 90s finally saw a president, Ange-Félix Patassé, come to power following elections, he was soon confronted by a mutiny and then coup attempts: first by former president Kolingba, then by general François Bozizé, which narrowly failed… only to re-emerge later. Landlocked in the heart of the continent, the CAR is at the center of a “great belt of crises” (as political scientist Dominique Darbon puts it) stretching from Angola to Sudan. One of the world’s poorest countries, despite its wealth of natural resources (gold, diamonds, uranium), the CAR was to experience more than two decades of crises at the dawn of the new century. Initiated by the coup d’état of General François Bozizé in 2003, the atrocities continued ten years later with the bloody seizure of power by the Séléka, a coalition of predominantly Muslim armed groups which, after overthrowing the regime, plunged the country into an abyss of inter-community clashes. The latest crisis was triggered by a coalition of rebels in 2020, withinstability constantly pushing back hopes of better days ahead: in 2020, 71% of the population was living below the international poverty line. The United Nations Humanitarian Coordinator estimated that 56% of the population would need humanitarian assistance in 2023, a 10% increase on 2022 (World Bank).

The break-up of the musicians’ diaspora is symptomatic of the fracture of a people dispersed by dictatorship and then political instability, illustrated by a sixty-something Sultan Zembellat swaying with his friends on the terrace of a Parisian brasserie in his video clip for “Rebecca”. Tired of being forced to sing the praises of a bloodthirsty Bokassa, who like Mobutu in Zaire wanted to make art the instrument of his power, several artists denounced or fled political pressure. Prosper Mayélé was imprisoned, while others took advantage of student visas to go into exile in Europe, especially Paris: Bhy Gao, Lea Lignanzi, Léonie Kangala and Sultan Zembellat. Others maintained their careers by moving closer to power, such as Charlie Perrière (Tropical Fiesta), who became Emperor Bokassa’s Minister of Culture.

“Rebecca” is a real “daddy-style” rumba sung by a giant of the genre with a sovereign voice, whose long, sustained notes make us feel all the torments of “poor Rebecca“. This dancefloor sweetness, which has nothing to envy of its Congolese counterparts, is only available on Youtube in a truncated and compressed version, which illustrates the scandalous inaccessibility of Central African musical heritage. To listen to this song in its original quality, a wealthy collector will currently have to pay over 40 euros on Discogs to buy the only CD copy of the album available online.

Zembellat, an expatriate in France, created the maziki.fr website in the 2000s to promote Central African music on the verge of extinction: “It raises the question of what we leave to future generations. The headquarters of Radio Bangui, a repository of musical works, was destroyed several times by mortar shells at the turn of the century.” In the absence of national archives and faced with the shortcomings of the specialized music press and the difficulty of navigating local media sites with limited resources (sangonet, centrafrica.com and Oubangui Médias), interested music lovers must therefore rely on private and often voluntary initiatives on volatile platforms such as YouTube (Fred Yapande, Shogi Productions, Musique Centrafricaine Beafrika Archive). Gathering the crumbs of a battered musical memory in the cloud, these digital diggers are brutally aware of the archive duty that every nation owes to its people.

“Pakapo, pakapo, boum boum!” As we explore the Youtube galaxy, we sometimes stumble across comets. What a pleasure it is to discover the zany energy of the character Bienvenu Paradis Gbadora, whose “uprooted dance” is even better appreciated on video with its frenzy of costumes and choreography, all wrapped up in the charming grain of 20th-century VHS clips and the crackle of an mp3 converted with the means at hand.

As always with untraceable comets, there’s virtually no information on the artist, song or album in question. Between the inspired samples, however, we can detect a good dose of irony and humor in the lyrics, which evoke Jesus’ birthday, wish us a happy new year and inform us that “it’s going to get hot tonight!“

At the start of 2024, the political and security situation in the Central African Republic remains unstable. Military operations are underway throughout the country against armed groups who regularly commit acts of violence. As always, the collateral victims of these conflicts include thousands of musicians deprived of a stage, and an audience deprived of their messages and thrills. Symptomatic of this asphyxiation: local authorities recently imposed a nationwide night-time curfew, which is hampering the recovery of an already atrophied music scene.

This mix also exists to remind us that the music market is not immune to the consequences of capitalist and post-colonial phenomena: the songs that reach our ears mainly come from politically and economically stable countries, in other words, the “winners”. Actively turning our ears to music from countries whose cultural influence is prevented by war and poverty is therefore a militant act. It’s a way of resisting the platform algorithms that systematically steer us towards familiar sounds. It’s a way of turning a deaf ear to the hegemony of the monotone voices of the “world that’s all right”, or would have us believe so.

I hope the listener will be as sensitive as I am to the infectious energy of the performances, the richness of the rhythms, the beauty of the languages, the brilliance of the melodies, as well as the amateurish charm of some of the recordings contained in this selection. Many of these tunes still resonate within me, and are a regular feature in my DJ sets, like distant friends who turn up unannounced.

Zooming In, Vol. 3 · Central African Republic

by Mixanthrope (African Beats & Pieces)

00:00 · Super Stars – Quartier Consigné

00:26 · Zokela de Centrafrique – Nostalgie de zokela

03:17 · Canon Star – The Yankata

04:17 · M Wanawa – Ceci-cela

07:19 · Formidable Musiki – Ti laso a ounzi awe

09:28 · JMC Quartier libre – Quartier libre

10:16 · Abakinlin de Bangassou – Gbèlin mando

12:26 · Ndaï Ndaï – Intrépide

15:31 · Francis Gon – Caresse des Les

20:21 · Gbadora – Gombana Bororo

22:28 · Vey-Zo – Ya Soso

25:04 · Losseba Ngoutiwa – Mensonge (Nvènè)

28:35 · Ozaguin – ?

31:54 · ? – ?

35:24 · Laskino Ngomateke – Soifa Tene

37:48 · Williano – Wambangana

39:30 · Zokela – Injection

42:39 · Les Yakuza de Centrafrique – Gbadouma

45:10 · Marina Reason – Ye ti kekereke

48:16 · Majora – Wa Vrin

50:31 · Canon Stars – Cousin

52:25 · Ashem & Senat Or Fée – Centro love

54:39 · Sultan Zembellat – Rebecca

58:42 · Centrafrican Jazz – Promesse

1:00:53 · Orchestre Vibro Succès – Dounia

1:04:42 · ? – Dikoboda Sombe