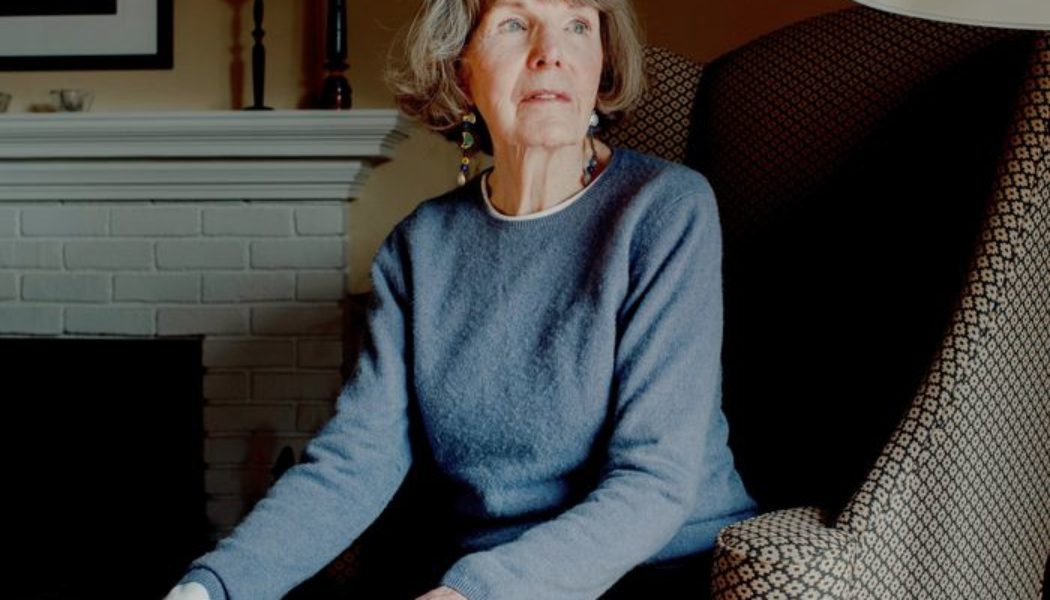

Mary Ellen Boyd plays pickleball, hikes and goes line-dancing once a week. When the 81-year-old retiree in Connecticut was diagnosed with breast cancer last year, she decided to have just part of her breast removed and skipped some treatment to keep her dance card full.

“Once I got my arms around it and really understood it wasn’t a death sentence, then next thing I wanted to do was say, OK, how do I maintain my lifestyle?” she said.

More cancer patients are making decisions about their own care, informed by evidence that some people with breast and prostate cancer can choose less treatment without hurting survival. The shift is sparing them from side effects, even as it presents risks of some cancers progressing further than they would have after more aggressive care.

“Patients have many more options today than they did even a few years ago,” said Dr. Jean L. Wright, a radiation oncologist and breast-cancer specialist at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. “It makes the decision process much more complicated.”

The deliberations are part of a move toward more personalized care for many types of cancer, made possible by more targeted treatments and more sophisticated tests. Doctors are seeing whether they can safely reduce surgery, chemo and radiation for a range of early cancers including head-and-neck, thyroid and lung.

Mary Ellen Boyd, at her home in Stratford, Conn., opted for radiation but not hormone therapy for her breast cancer.

Photo: Lila Barth for The Wall Street Journal

Cancers of the breast and prostate are among the most common forms in the U.S. and the second-leading cause of cancer death for women and men, respectively, behind lung cancer. But for many patients who are older and diagnosed early, cancer won’t be what kills them. That reality is giving them more latitude in their choices as treatments evolve.

John Thomas was diagnosed with early-stage prostate cancer in 2020 that his doctors said was small and slow-growing. Mr. Thomas expected he would need treatment. But his doctors told him some patients can safely monitor such tumors and delay surgery and radiation that risk side effects including incontinence and erectile dysfunction.

Mr. Thomas decided to monitor his tumor. The 62-year-old teacher in Philadelphia is retiring at the end of the school year and plans to travel the country in a customized SUV he nicknamed “the Beast” between check-ins every six months.

“I don’t want to deal with those side effects if I don’t have to,” he said. “It’s like an interest-free loan.”

After being diagnosed with early-stage prostate cancer, John Thomas made a plan to travel the U.S. in a customized SUV he calls ‘the Beast’ while monitoring his tumor.

Photo: John Thomas

Alexander Kutikov,

a urologist at the Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia and Mr. Thomas’s doctor, said a big part of his work is making sure men with early stage prostate cancer know delaying treatment can be just as good of a choice. “People land on their preferences pretty quickly,” Dr. Kutikov said.

Some patients want to do more to put cancer behind them and avoid further treatment when they are older. Lynette Stevenson, a 63-year-old housekeeper in Detroit, chose a lumpectomy after being diagnosed with breast cancer in 2021. She said she underwent both radiation and hormone therapy afterward to take the best shot at saving the rest of her breast and her life.

Radiation is less taxing and more targeted than it used to be, and some patients can get the same benefits in fewer sessions, radiation oncologists said. Miss Stevenson said she gets hot flashes from the hormone therapy pills but is doing well. “I had heard so many war stories about cancer, but it’s changed so much,” she said.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

How have you or a loved one made decisions about treatment for cancer? Join the conversation below.

General health is important in determining a course of treatment as many people live longer. “Our definition of an older patient is changing,” said Dr. Michael Dominello, a radiation oncologist at the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Center in Detroit and Miss Stevenson’s doctor.

Nancy Smith, an 82-year-old retiree in Austin, said she decided against radiation after breast-cancer surgery in 2021 because her doctor said she wasn’t at high risk of recurrence.

Attending weeks of appointments would have been difficult, Ms. Smith said, and she was wary of radiation’s side effects, which can include fatigue and skin irritation.

“I’ll continue my mammograms every year and hope for the best,” she said.

For some women over 65 with early breast cancer who are taking hormone therapy, the recurrence risk in the decade after surgery without radiation is about 10% compared with some 1% for patients who get radiation, research shows. Most patients should take hormone-therapy pills for at least five years to help prevent cancer from appearing elsewhere in the body, research shows.

Many patients stop taking the pills early because of hot flashes or bone and joint pain. Patients who won’t take the pills for five years should strongly consider radiation, oncologists said.

Mary Ellen Boyd got radiation therapy once a week for five weeks, putting off more aggressive treatments after her surgery.

Photo: Lila Barth for The Wall Street Journal

Callie Wilson, a 73-year-old retired nurse in Washington state, said she stopped taking hormone-therapy pills in 2021, 2½ years after breast-cancer surgery, because stiffness in her ankles was causing her to trip and fall. She said she was grateful she had gotten radiation because she didn’t anticipate she would stop taking the pills: “How could I know?”

Some older patients choose radiation and not hormone therapy without solid evidence of how that affects survival, said Suzanne Evans, a professor of radiation oncology at Yale School of Medicine. Dr. Evans is among doctors exploring whether a genetic-tumor test can help determine which patients on hormone therapy can skip radiation. Some tests already help assess recurrence risks and whether patients need chemotherapy.

“We’re getting so much more specific,” she said.

Ms. Boyd, a patient of Dr. Evans’s, got radiation but not hormone therapy after learning the treatment would only marginally improve the chances of keeping her cancer in remission. The threat to her hiking and dancing wasn’t worth it, she said.

Ms. Boyd got radiation therapy once a week for five weeks. She took a trip to Rome with her family last year to celebrate when it was over.

“If it comes back, I could get a mastectomy,” she said. “I still have options.”

Mary Ellen Boyd says that if her breast cancer recurs she could opt to get a mastectomy.

Photo: Lila Barth for The Wall Street Journal

Write to Brianna Abbott at brianna.abbott@wsj.com