Australian start-up Loam is using fungi to help crops capture carbon in the soil—and keep it there. It could be a game-changer for farmers and the fight against climate change.

FORBES, New South Wales—

When agronomist Steve Nicholson purchased his now 4,000-hectare property near Forbes, New South Wales (NSW), Australia, in 1999, he knew it had potential. It was near a good town, close to major grain buyers and had plenty of room to grow his staple crops of wheat, barley, and canola. But the property was rundown, and after sending away soil samples for analysis, the first major challenge presented itself: Organic soil carbon levels sat at just 0.01%, well below the area’s already low average of 0.5 to 1.2%.

“We knew that if we could put more carbon in the soil, we would get better yields, more resilience in our cropping system, and more productivity to be more profitable,” says Nicholson. How he would go about doing that, though, was a big question mark.

For farmers, the holy grail of agricultural productivity is carbon—not fertilizers like nitrogen, potassium or phosphorus. The main component of soil organic matter, carbon is associated with higher nutrient uptake, better resilience to both drought and extreme rainfall, erosion reduction, and a reduced need for fertilizers. But while organic carbon was once present in all agricultural land, it’s been stripped out of the soil by modern industrialized farming practices. In NSW, research indicates organic carbon levels would have sat at over 12.5% prior to European settlement. Worldwide, the loss is much higher, with soils having between 20 to 60% of their carbon content.

Immediately, Nicholson set about to do everything he could to increase carbon levels on his land: Stubble retention, zero tillage, high soil cover, using the right herbicides, and planting the correct varieties of plants at the right times. Yet, even though he utilized the best-known carbon farming practices, organic carbon levels only increased to 1.7% over a 20-year period.

“It’s still nowhere near where I want it to be,” says Nicholson. “I’d love to think I can get it above 3%.”

To do that, he turned to Loam Bio, an Australian start-up that is using fungi to increase carbon levels. In April 2023, Nicholson’s farm will be one of the first commercial properties sowed with seeds inoculated by Loam. For both Loam and Nicholson, restoring carbon to farmland isn’t just about increasing profit or productivity—it’s also about fighting climate change. More than five billion hectares of the world’s surface—or about 38%—is covered by agricultural land, of which 10% is permanent cropland. If Loam’s technology works and is employed on a mass scale, it has the potential to create one of the largest carbon drawdowns from the atmosphere on Earth.

“It could be a game-changer,” says Nicholson.

Endophytes for the planet

Set against a pastoral backdrop of rolling brown hills dotted with gum trees and cattle, Loam’s office could be mistaken for just another farm shed in Orange, NSW.

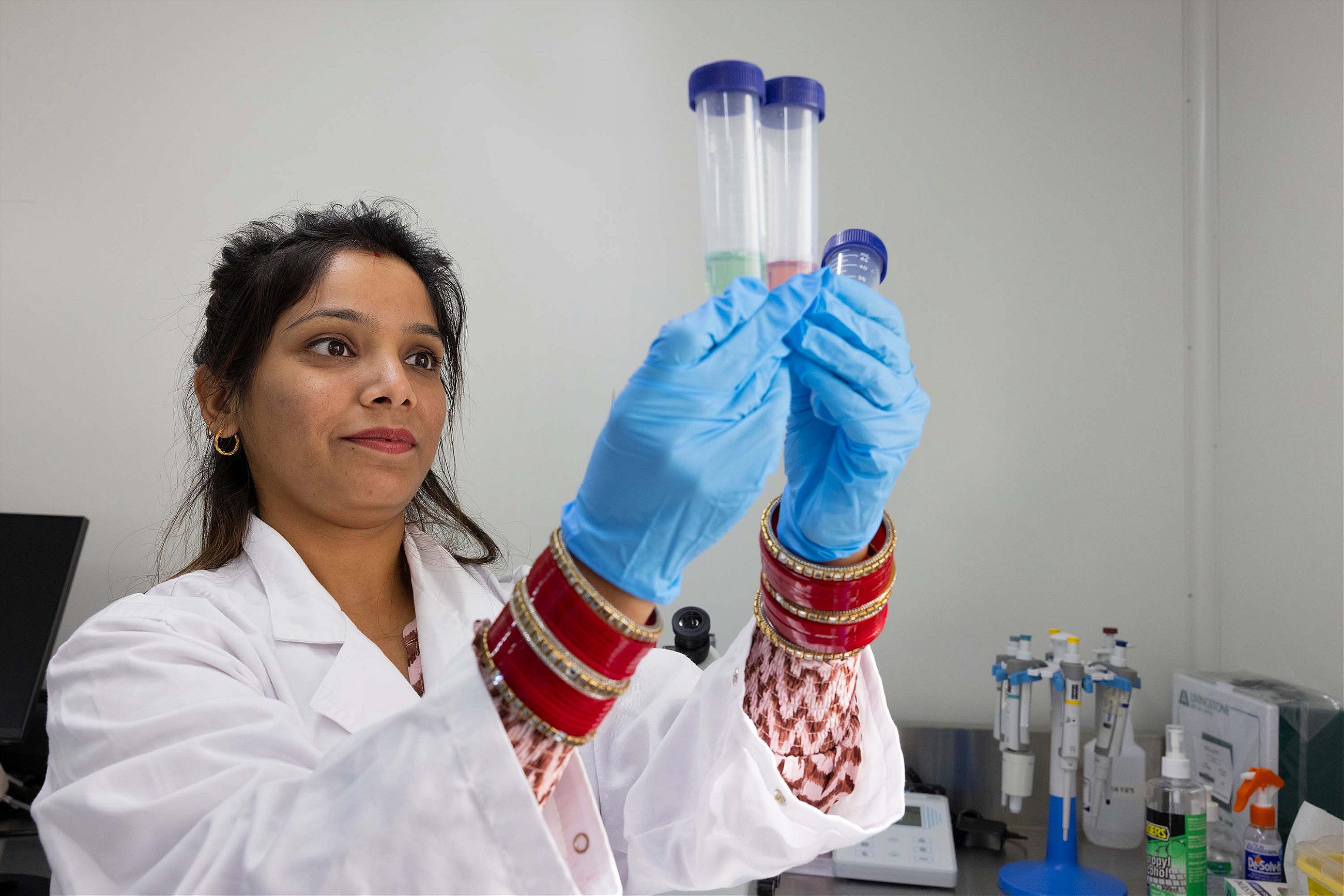

But inside, the energy of a start-up permeates the open-plan space. Tradespeople are at work installing the beginnings of what will be Loam’s on-site fungi library, built to house the over 2,000 species already in its collection.

These specialized fungi, or endophytes, are at the heart of Loam’s technology. They’re the same naturally occurring organisms that allow plants to thrive in otherwise inhospitable environments. From the Canadian Arctic to the sulphurous heated grounds of Yellowstone National Park, they form symbiotic relationships with plants, allowing their hosts to develop better nutrient efficiency and water retention while improving microbial diversity below ground.

“We find them through ‘bioprospecting,’” explains Pip Grant, Loam’s executive program manager. “In arid environments with no water in sight, we’ll find something that’s green and thriving and then analyze what’s happening at the root system to keep it alive in that environment.”

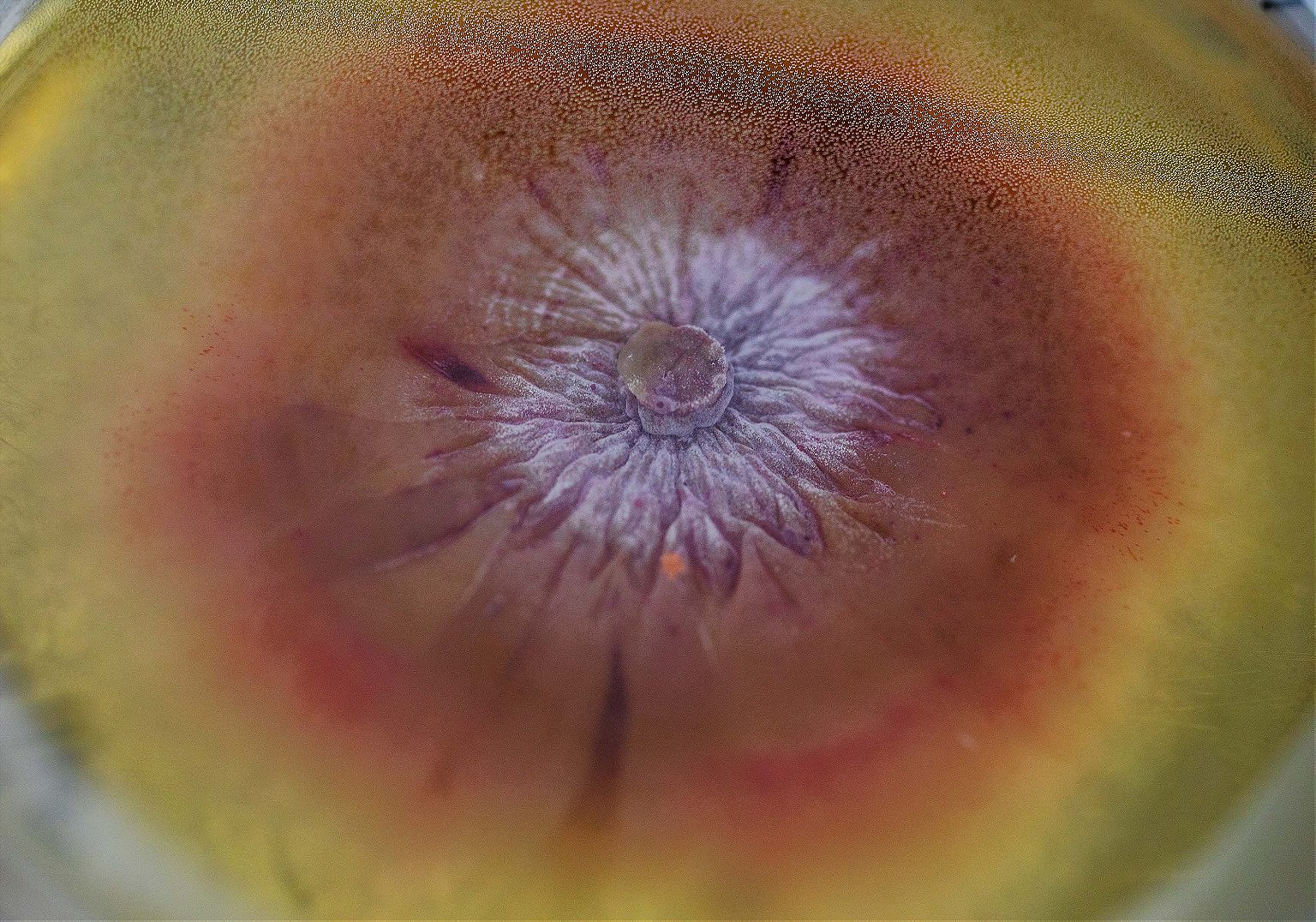

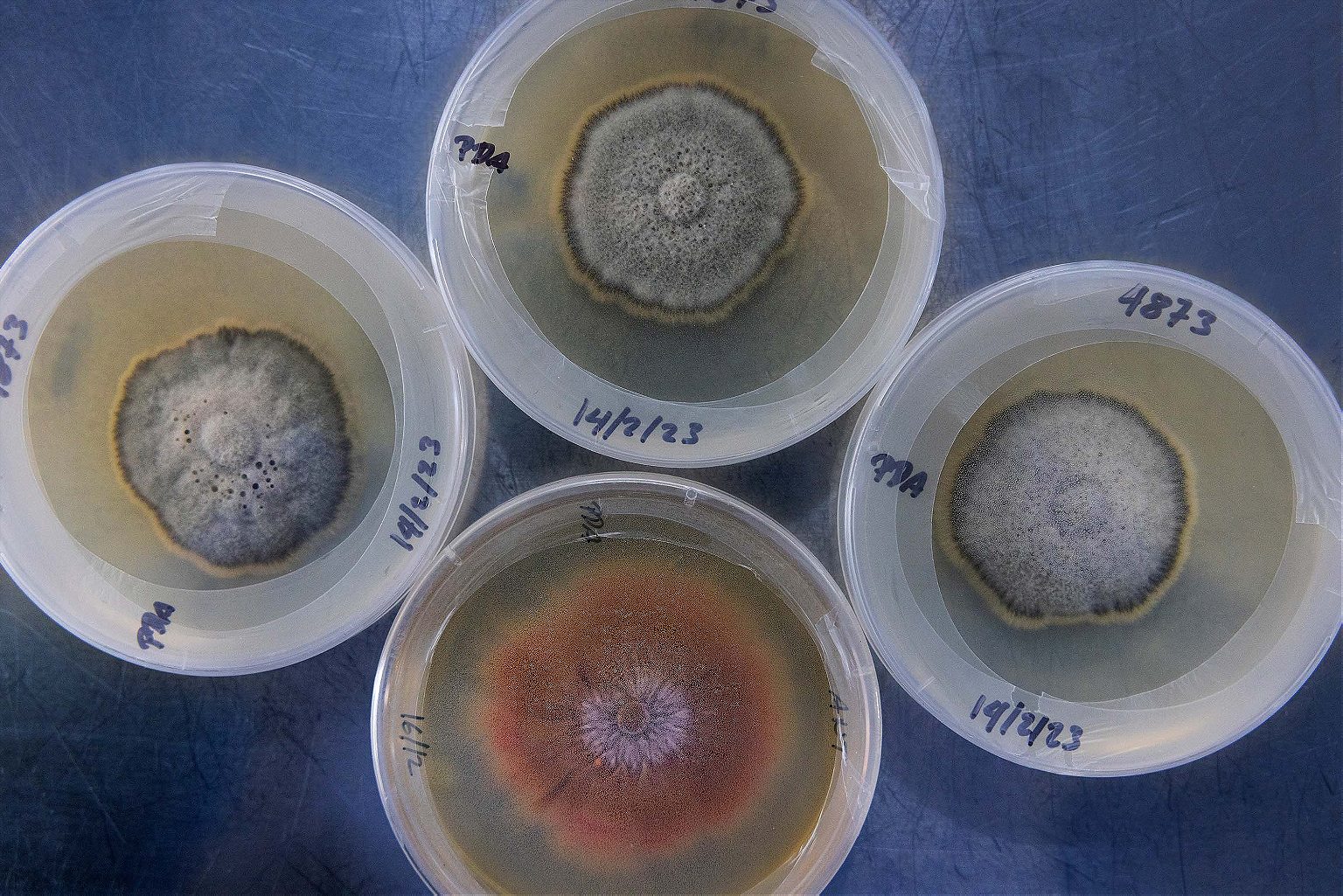

The harvested fungi—found within plant tissues—are displayed in petri dishes in Loam’s small on-site lab. Each is carefully analyzed to determine which soil types and host species it could pair with, and to ensure only beneficial microbes from indigenous species enter the soil. They range from oily white to brilliant strands of pink, and there’s one that looks distinctly like a slice of moldy orange, its rind fuzzy and black.

Loam’s scientists are most interested in these black fungi, called dark septate endophytes. They’re capable of converting CO2 from the atmosphere into carbon in a way that stabilizes carbon aggregates in the soil for hundreds, or even thousands, of years. Loam uses these selected endophytes to carefully inoculate seeds that farmers plant.

Loam’s preliminary trials—over 6,000 conducted across 29 locations in Australia and the United States—demonstrate that crops grown with its seeds significantly improve carbon soil storage. While farms using some carbon management practices may have between zero and two carbon units per hectare (with a carbon unit being equivalent to one ton of CO2 that has been removed from the atmosphere), land planted with Loam seeds have between three and six carbon units in a single growing season (usually one year).

“[There was] a clear and evident impact—which even surprised me,” says Yolima Carrillo, a third-party researcher at Western Sydney University’s Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment, who has helped evaluate Loam’s trials over the last three years. “I wasn’t expecting it was going to be so clearly evident how stable and resistant the soil carbon was going to be.”

A “second crop” for farmers

Carbon stability is also crucial to Loam’s performance in the carbon markets – a key part of its operating and financial structure. A diverse crew assembled to create Loam: agronomist Guy Webb, farmers Mick Wettenhall and Tegan Nock, filmmaker-turned-cattle-breeder Frank Oly, and clean tech expert Guy Hudson. Originally conceived as a non-profit in 2015, Loam registered as a for-purpose enterprise in 2019 to scale quickly (Its non-profit arm, SoilCQuest, is still in operation and is the largest shareholder in Loam). Now employing over 70 people, Loam doesn’t just provide farmers with its inoculated super-seeds. It also assists growers in registration and verification for carbon schemes such as The Australian Government Emissions Reduction Fund program, a total product package it calls SecondCrop.

“It’s adding another commodity—carbon—to existing operations without having to forgo anything,” explains Torbyn Heinzel, carbon projects lead. “Farmers think they’re going to have to plant trees and forgo growing their crops or running their sheep. But we’re applying a seed treatment to what they’re already planting, so it’s not a massive change to their operations.”

This misconception has been just one of Loam’s marketing challenges. Until recently, phrases like “climate change” and “regenerative agriculture” were met with skepticism and sometimes derision in rural Australia, where carbon-sequestering solutions are often seen as “snake oil.”

But as climate disasters become more prevalent across Australia, that mentality is slowly changing. From 2017 to 2019, farmers slid into debt and devastation during one of the worst droughts on record since the 1890s. That was followed by the Black Summer of 2019-2020 (when bushfires engulfed some 24 million hectares), the pandemic, and, most recently, 2022’s catastrophic floods.

“It’s horrible what we’ve had to go through for [climate change] to be a collective realization, but it’s exciting that farmers are looking at coming online not just purely from that productivity perspective, but to do something about a problem they’re facing on a daily basis,” says Nock. Including Nicholson’s farm, Loam anticipates it will have 15 projects registered in time for sowing, with 100 on the books before the end of the year.

“Farmers are just looking for something they can do to be part of the solution,” says Nock. “It’s pretty inspiring.”

A global solution

Commercial farmers aren’t the only ones who are motivated. When Loam was featured on Netflix’s Down to Earth with Zac Efron in 2022, calls started pouring in from gardeners and hobby farmers. They all wanted to get their hands on Loam’s super-seeds.

“It’s not going to be sold at Bunnings anytime soon,” jokes Grant, referring to the ubiquitous Australian home improvement mega-chain.

Therein lies perhaps Loam’s most significant challenge to date: While most start-ups start small and struggle to develop enterprise-sized solutions, Loam has been built for farms greater than 5,000 hectares in size. Yet its ultimate goal is to make its technology available for smallholder farmers in developing countries. Though they produce one-third of the world’s food and stand to gain the most from profits generated by a “second crop,” they’re typically excluded from carbon markets.

“We really need to figure out how these smallholders can not only access technologies to sequester more carbon, but profit from natural capital markets,” says Grant.

Loam plans to run a trial with small farmers in Brazil later in 2023, but the barriers are significant. They’ll need to assess the supply chain to ensure deforestation hasn’t taken place for carbon projects, find the right endophytes to work with the right crops within the specific soil structure, and navigate cross-cultural barriers—all while operating on a much smaller scale.

“It’s not uncomplex and it’s a lot more intensive dealing with 500 [small holder] stakeholders, than one stakeholder with a 10,000-hectare farm,” says Grant, noting that the baseline reporting needed to register for carbon projects is time-consuming and expensive.

Until then, Loam has already begun its expansion into North America. Trials have begun in Canada, focusing on crops like soy and corn, which have the greatest amount of land cover, like soy and corn. And although it will be years before it will be able to evaluate its product’s success in “real world” settings, the farmers who have already signed up are optimistic.

“There’s no downside. We’ve got to produce real food to feed real people, because that’s the secret—we just need to have good, sustainable agriculture,” Nicholson, the farmer in Forbes, says. “And if we can increase carbon levels across massive areas of agriculture? Everybody wins.”

Any sustainable food game-changers on your radar? Nominate them for the Food Planet Prize.