Hanging up outside of the Hoboken mayor’s office are crooked and out of order framed pictures of past mayors. Very apropos for a city that’s known for its crookedness. Fortunately, Hoboken’s current leader, Mayor Ravi Bhalla, 46, has been straightening out the Mile Square City since being elected to city council in 2008. Bhalla has spent his life fighting for others. It’s part of his Sikh faith – Bhalla was New Jersey’s first Sikh mayor when elected in 2017 – and it’s his faith that unfortunately made him a target for being bullied growing up and being labeled a terrorist while running for mayor.

I recently spent the day with His Honor, where he spoke openly about having his own civil rights violated, his immigrant parents and why his wife is so damn important. After listening to his story, I quickly realized this soft-spoken and very approachable politician really embodies the American experience.

Ravi Bhalla was born and raised in New Jersey. He lived in a two-bedroom apartment with his parents and older brother in West Paterson, about 45 minutes outside of New York City. He played tennis growing up and was an all-state doubles player his senior year in high school. He was also president of his local Junior State of America chapter – a youth organization that focuses on public issues. Then he went to college, where he was exposed to a whole new world.

Moving to the west coast to attend the University of California, Berkeley was a cultural shift for Bhalla, who jokes that he was picked on for his New Jersey accent. There was a very robust East and South Asian population in the Bay area and the student body, giving him more of an affinity towards his South Asian background. “I was going from a largely homogenous all-white school to a very diverse population in Berkeley,” he says. “It was very refreshing and it broadened my horizons and encouraged me to think about various issues.”

After Berkeley, Bhalla earned his masters at the London School of Economics, before returning to the U.S. for law school at Tulane University in New Orleans. Of the three cities, the Crescent City was his Goldilocks. “You can get lost in London because it’s so big and a truly international city. Berkeley is smaller and has a funky beat to it which is nice. New Orleans is medium-sized. It just had a great tradition of music, culture, food and the law school had a rigorous curriculum, so in some way, it helped you balance your life.”

As mayor of the fourth densest city in the country, he’s still learning to balance his life. “I’m always on the job, I’m responsible — it’s part of your duties as mayor – but I do my best to balance work with family. I have to make time to make sure to be a good father, a good husband. I need to take breaks – during COVID I haven’t had a break. I’ll spend an hour at the park to have a baseball catch with my son. We take family bike rides on the weekends. We go out to dinner every Friday night.”

Part of his ability to balance work and life is from his very supportive wife, Bindya. They met in London where she was practicing human rights law and he was there on business. Through mutual friends, they met for what Ravi scheduled in his day as a quick 30-minute cup of tea on Oxford Street. “It was a check of a box of things to do that day,” he says, “but it turned into a 90-minute-long affair.” He asked her out the next day. They married in 2003. Bhalla exclaims: “I definitely married up, and got her to come from London to Hoboken.”

She’s been his rock since. “I go to her to discuss civic sense and policy matters. I trust her judgement and character more than I trust my own. When I’m not sure about something we talk it through. She’s got some special instinct that’s a huge asset to me. She has no official role in City Hall but as a life partner she plays a very important role.”

Bindya is currently the executive director of Manavi, a non-profit that focuses on combating violence against women in the South Asian community. “It’s very sobering work,” says Bhalla. “Unfortunately, domestic violence transcends all communities, ethnicities, religions and it’s also a problem in the South Asian community.” In a Facebook post, Bindya wrote that when she worked for the International Rescue Committee and had to move temporarily to Sudan, Ravi supported her choice and took care of their daughter, while managing his own career. While Ravi was running for mayor, Bindya was unstoppable. She canvassed block after block flipping those voters that needed convincing.

Bindya is from Iran. Her parents still live there, but due to President Donald Trump’s travel ban, they are currently unable to visit. “They used to come to visit Hoboken on a regular basis, but once the Muslim ban was put in place it literally separated our family,” Bhalla explains. “It separated my in-laws’ ability to visit their grandchildren, their daughter. I love my in-laws. They just can’t come for no reason other than where they’re from.”

Ravi’s own parents, who live about 40 minutes northwest of Hoboken, were born in India. His father came to the United States and got his Ph.D. in chemistry at Penn State, where he and Bhalla’s mom lived on campus in a trailer home. “We heard stories about their toilet breaking in the first days of being in the U.S. and not knowing how to navigate.” Bhalla’s father went on to work for Westinghouse in nearby Bloomfield, New Jersey, and became an inventor. He developed nearly 40 patents. “He was a smart guy, but it skipped over me,” Bhalla says with a self-deprecating laugh. He then started his own factory to give his kids a pathway to having their own business. Ravi’s first job was working the line at the factory for minimum wage. “Unfortunately, physics was not my strong suit,” he says.

His parents influenced him by their actions. “They never said do this, do that. But as little kids we tend to mimic behavior of people you look up to. They always worked hard, were honest. They were aware of their surroundings. We’re here not for our own benefit, but to care for our community. Whether it’s religious community or community in general. It’s part of my approach as mayor.”

Ravi’s religious community is Sikhism, a monotheistic religion founded in Punjab in the 15th century. It was very difficult growing up a Sikh, he says. “I was a person of color, I was the dark-skinned kid in school. The N-word was directed at me on a regular basis and I was routinely bullied based on my skin color and religion, both verbally and physically because of the Sikh tradition of not cutting my hair.”

The significance of hair in Sikhism is sacred. “The long, uncut hair is viewed as something God gave us. It gives us strength and fortitude,” he says. When it came to being bullied about his faith, his mother had one ground rule. “She said if anyone touched or tried to pull my hair, she gave me permission to defend myself. One instance the teacher called my mother in to say I was in a physical altercation, my hair was pulled. My mother said ‘If he’s just being pushed to the ground, I told him to report it to you, but if anyone touches his hair, I gave him permission to defend himself, he has every right to.’”

Bhalla was forced to defend his faith when he ran for mayor in 2017. Just days before the election slanderous flyers calling him a terrorist were left on people’s car windshields. At the time he told the press these flyers brought to the surface an “undercurrent of racism” that he saw throughout the campaign. This can be looked at as one of those “who’s laughing now” moments, because Bhalla won.

As part of his Sikh faith, Bhalla wears a bracelet that represents a circle – a belief in reincarnation, that there’s no end or beginning in life. “Holistically, whether it’s the long hair or turban, it is supposed to represent our inner beliefs.” He also has a tattoo on his upper left arm. It’s of the Sikh symbol that’s equivalent to the Star of David in Judaism or the Cross in Christianity. He describes the Sikh faith as one about peace and being radical egalitarians. “It’s not just a faith, it’s borne as much out of necessity for social reform, like gender equality and quality among classes. In the eyes of our creator, we are all equal, no matter our gender, faith, sexual orientation, our financial status, social status. There’s no priestly class or intermediary between you and the creator. In our scriptures, we draw from Jesus, Mohammed, various faiths. There is no one right path, everyone has their own path. It should be respected. We don’t tell people to convert.”

Bhalla says we are tasked to serve all humanity, that “we are all one!” and the Sikh beliefs and messaging is clear: 1) fear no one and instill fear in no one, 2) choose your path, 3) be proud of who we are, 4) nobody has a monopoly on the truth, 5) we are all equal, and 6) uplift society.

One of Bhalla’s proudest cases as a lawyer involved that of a fellow Sikh. Amric Singh Rathour wanted to be a traffic control officer in the New York Police Department. A traffic control officer directs traffic and issues parking tickets, they don’t carry weapons. “He passed all of the tests – physical, written and psychological tests — and was told he qualified but was told he needed to remove his turban and shave his beard. That is consistent with the uniform requirement,” Bhalla explained. “He asked for a religious accommodation – an employer is legally required to consider. He was denied that accommodation. The central debate in those disputes is this accommodation you’re asking for going to interfere with his job duties. There is nothing about being Sikh that makes you less able to direct traffic or write a traffic ticket. It’s fairly obvious.” Bhalla was successful and says this case helped open the door to make the Sikh community a part of public service. “And now there are over 80 Sikh police officers in the NYPD.”

Bhalla has had his own civil rights violated “a number of times” but one that stands out garnered national attention in 2003. While visiting a client in the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn, New York, Bhalla was told he couldn’t visit his client because he had to take off his turban. “They violated my 1st amendment rights – violation of his right to practice his faith; 4th amendment rights – violation of privacy; and my client’s 5th amendment rights – right to counsel.” He filed a complaint with the office of the inspector general, the federal agency that deals with complaints with the bureau of prisons.

“They changed their policy not just at that facility but nationwide to allow Sikh’s, not just attorneys, but all visitors to any detention center. I just remember driving back from Brooklyn in a state of shock. Having your rights so blatantly violated was sadness, but I tried to channel that into advocacy, positive actions and to change the policy.”

When it comes to talking about Sikhism with his two children, it’s an open discussion. “We tell them to be proud of who they are but also to exercise humility and instill the same values my parents instilled into me. We let them know that there are not a lot of Sikhs in Hoboken – about 10-15 families — to still be proud of it. I look at my upbringing going to public schools and being physically assaulted and my son’s upbringing. He’s the coolest kid in school because his dad’s the mayor. It’s a great progression. If nothing else, as mayor I’ve protected my kids from what I went through as a youngster.”

As a practicing attorney for 18 years, he’s been an advocate for change in his own profession. “To this day, the legal profession is extremely male-dominated. I don’t think people appreciate the extent of how male-dominated the profession is. Whether it’s people at the partner level, judges. The playing field is nowhere near leveled for female attorneys. I see it gradually changing and that’s because of women and you see extraordinary female attorneys, and most notably the passing of Ruth Bader Ginsberg, we learned about her life as both a judge and in private practice. Women have been given nothing and earned everything they achieved.”

Bhalla started his own law firm in 2005 with the bare minimum — “I had a computer, letterhead, business cards and a pen in a small room” – and was quickly exposed to the world of politics when two Hoboken city council members turned to him for representation. They were being sued by the mayor over a budget impasse, and the mayor ordered a shutdown of all city services. Bhalla won the case and it gave him tremendous insight into how government and politics operate in Hoboken. “I realized the decisions made by the local officials are the ones that directly impact my quality of life and my future in town, opposed to the federal or state government.”

Ravi started honing in on the issues. In 2008, those were fiscal responsibility, flooding, lowering taxes, responsible development, open space and quality of life. “I started watching city council meetings and felt there was nothing remarkable about these council members and thought I can perform those functions as well if not better.”

He was told he wouldn’t win. “I wasn’t Italian, Latino, a senior, labor, or part of the ‘old Hoboken’ regime. I was told my turban and beard would not go unnoticed and that my faith and ethnicity was a liability to achieve success and be elected.”

That made Bhalla work harder, blanketing the town while running a very disciplined campaign. And when it came to the debates, between 12 candidates vying for three spots, he crushed it. “I immediately saw voters’ impressions change. People walked up to me saying ‘You really did well!’ We tried to persuade voters that I was involved in politics for the right reason. Unfortunately, Hudson County has a history of getting involved for not being altruistic.”

Pundits, however, said there was a conflict between religion and leading politics. Bhalla disagreed, saying it was his ability to deliver on his campaign that was a bigger deal to voters than his personal life. “If you can show you are the most qualified it doesn’t matter what your gender or race or faith is.”

Ravi wants the Mile Square City to pivot from being a transient town to one where people set up roots. “I never thought I’d be one of those parents with strollers,” he says, but he became one, twice, with daughter Arza, 12, and son Shabegh, 8. And like most urban parents, the s-word was briefly discussed.

“We never seriously thought about moving to the suburbs. We got to the fork in the road when our daughter was about two years old and she was losing her friends to other towns in New Jersey.”

But Bhalla decided to stay for Hoboken’s quality of life.

“You can walk blocks and eat a nice meal and not be dependent on a car. It’s up to the government to create these local conditions. Create conditions for people to stay here for the long term.”

He’s noticed that after decades-long gentrifications more people are following in his footsteps. The importance of creating affordable housing to accommodate families has never been so important. He’s strengthened rent control laws and created inclusionary zoning, where a percentage of units must be affordable.

“People shouldn’t need to choose between staying here or moving to the suburbs.”

Bhalla does have a car and deals with the hassle of finding a parking spot. “I drive around just like everyone else and get parking tickets. I was just online paying one,” he tells me as I walked into his office. “It’s a dance, it’s part of city living. I appreciate the frustrations, but when you look at things holistically, there are trade offs in life and this is a great trade off to have.”

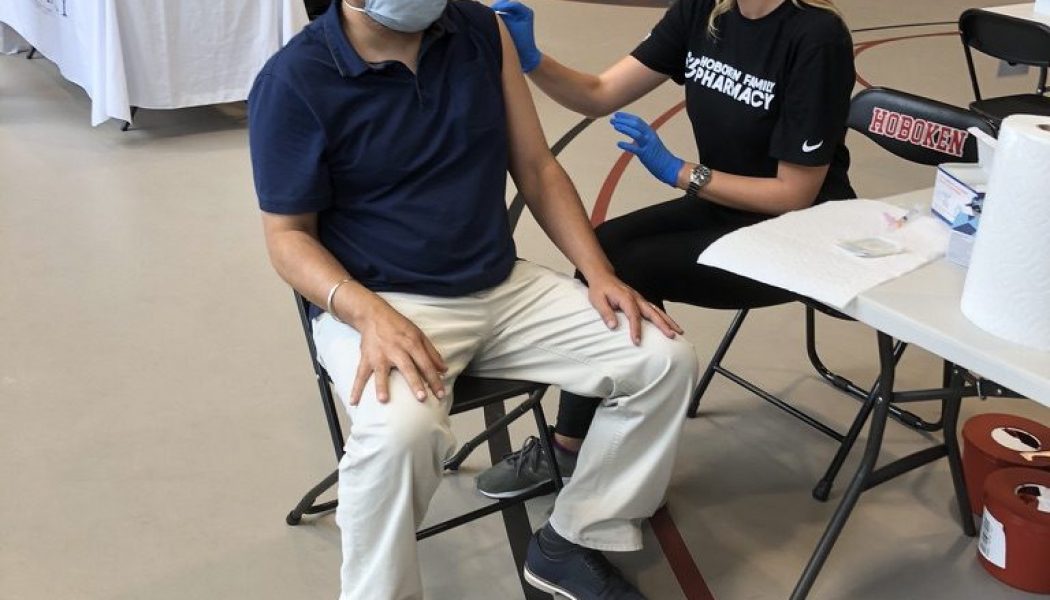

March 13, 2020 was the most stressful day for Mayor Bhalla. It was when he realized the gravity and impact COVID-19 would have on his city of over 50,000 residents. “This is not a water main break or a flood event, or a nor’easter. This is a very unique circumstance. Having that realization is hard to describe.”

Bhalla, who had already called a state of emergency, called for a complete shutdown. Hoboken was the first municipality in the United States to make this decision, as well as issuing the first self-isolation order in the country.

“This was a move no mayor or jurisdiction in the country took.”

Prior to March 13, Mayor Bhalla closed the schools. He shut the bars down beginning March 14. His administration was urging people to heed the warnings from the U.S., east Asia, Italy, and the rest of the world.

“I received emails from Hoboken residents who were in Italy at the time, pleading with me to not make the same mistakes. ‘Please take this seriously. This is not a hoax. People are suffering.’ I did not share these with my administration or senior staff. I walked out of City Hall and saw bars at full capacity despite having the measures of wearing a mask and social distancing, acting like there was no pandemic; had a spring break atmosphere. I was very concerned with bars and restaurants staying open and the virus spreading exponentially through Hoboken through reckless activity. Our calls to stay home, be careful, avoid crowded gatherings were not being heeded.

“Discussions were stressful. We were not panicked but this was the first and only time a feeling of crisis set in into my psyche. It stayed with me through that day. We relied upon advice from our Office of Emergency Management, heath experts, the health department, trusted senior staff and absorbed all of this information. We had very rigorous and passionate discussions about what to do.”

They talked about lowering capacity to 50 percent, but at the end of the day, based upon all the information at his disposal, it came down to instincts. “It counts for a lot,” he proudly says. “Instincts took over and ultimately led to my final decision. Instinct counts – trust it. The obligation as mayor is to protect the public.”

As with any major decision made by a politician, there was immediate pushback from within his own circle of trusted advisors, who went over the political repercussions this would have. “I put my foot down and made it clear that if this decision costs me the ability to run and succeed in the next election, but I can save just one life, then this is the right decision. I can live with the decision. It was a time to throw politics to the wind for the health of our residents.”

His chief of staff met with 20 bar and restaurant owners the very next day explaining it’s not lost upon the mayor, the economic impact this will have.

“These small businesses are the backbone of our community, but I couldn’t prioritize profits over people. People come first. If we don’t have residents who are healthy, they cannot visit businesses,” he says to me.

Hoboken’s next mayoral election is in 2021. Ravi has yet to make a final decision to run for re-election. He also hasn’t thought about future political aspirations because he doesn’t make plans. “I let life guide me and take one day at a time. That’s a life philosophy of mine. When I moved here, I had no idea who the mayor was, let alone thought of becoming the mayor 20 years later. If nothing else happens and I serve four years as mayor, it’s a privilege of a lifetime.”

But if he does run again, he knows he can on his record. His first act as mayor after being sworn in at his house on January 1, 2018, was driving to City Hall to sign an executive order making Hoboken a fair and welcoming city, formerly known as a sanctuary city. “It means the executive order declared by law – and supported by the police – the city of Hoboken will treat all people no matter what their gender and immigration status equally. And more significantly, the Hoboken police department would not allocate any resources toward the enforcement of federal civil immigration laws. We want to make sure people feel welcome in Hoboken and not be afraid of going to the police. Their immigration status is not questioned if you go to the police. Everyone had equal access for all city services.”

He also turned every single occupancy restroom into gender neutral ones – the first city in New Jersey, and one of few cities nationally, to pass such a law. Hoboken subsequently received a perfect score from the Human Rights Campaign for LGBTQ policies.

Whether he runs again or not, Bhalla knows what he wants to focus on. “If I can continue helping people that would be the best use of my time.

Ravi Bhalla is a very approachable and simple man. During our lunch break, he picked up a sandwich at a nearby deli. His desk is from his law firm, the paint on the walls in his office is from the previous administration, and he tells me, “I didn’t even have a computer when I started, so I use my own.”

Lying on the floor in a corner of Bhalla’s unadorned office, is a framed photo of Robert Johnson. He loves Robert Johnson. While in law school he toured the Mississippi Delta and Tennessee to check out Robert Johnson sites. Hoboken has its own music history, being the birthplace of Frank Sinatra. Is the mayor a fan?

“A casual fan. It’s part of the swearing-in process,” he quips. “Two houses down from me is the house he lived in as a teenager and my house is where his parents lived.”

And as a New Jersey native, how can we not get him to weigh in on which Garden State rock star he prefers: Springsteen or Bon Jovi.

“Springsteen. He’s struck a chord so to speak in touching upon the lives of working families in New Jersey and this country, which makes me proud to be from New Jersey.”

His favorite Springsteen song? “I like “Brilliant Disguise.” Was that not the right answer?”

It’s not “Born to Run,” but he’s certainly fit to do so.