That’s raised some suspicions that the goal to eliminate more than half the nation’s emissions may be more of a political aspiration than a meticulously detailed strategy.

“They were getting all kinds of pressure from progressives and the environmental left — if they said anything less, it would have been perceived as underwhelming,” said Frank Maisano of the Bracewell’s Policy Resolution Group, which represents power companies and other energy firms. “I don’t think there is any analysis.”

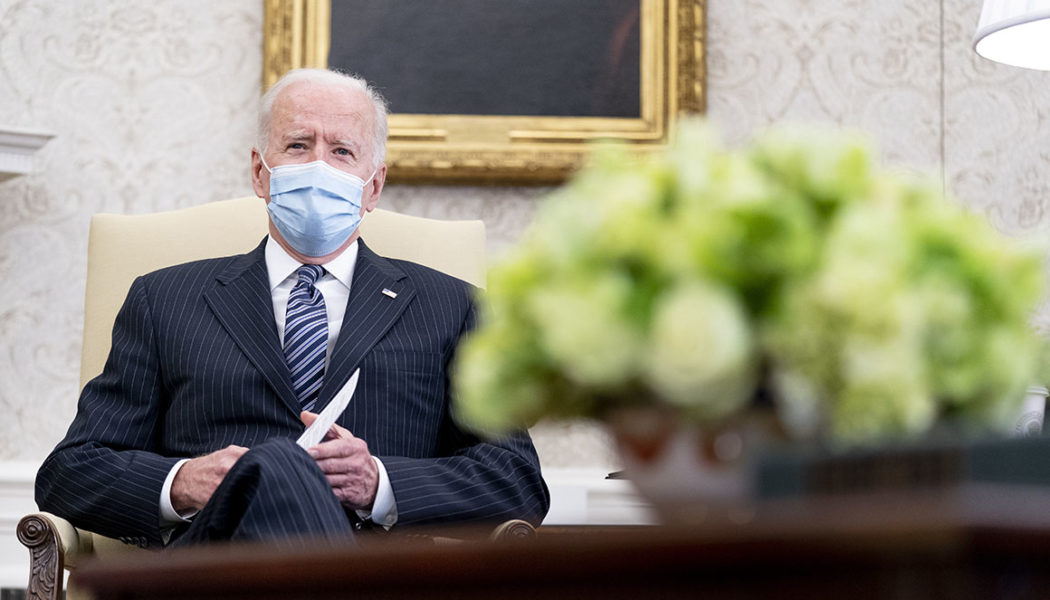

Republican lawmakers sought to pull information on the administration’s aims from EPA Administrator Michael Regan at a budget hearing on Thursday.

“After transportation and electricity, the economic sectors with the highest emissions are industry and agriculture,” Rep. Buddy Carter (R-Ga.), asked the EPA chief. “Can you please tell us if the new regulations on these sectors are part of the president’s plan to achieve the (target)?”

Regan declined detail specific measures, responding that while EPA fed emissions data to the White House to develop the target, the effort would be “a government-wide approach” that is “not squarely on the shoulders of EPA and EPA’s regulatory authority.”

So far, the most detailed information about the White House’s math that lawmakers received is from the administration’s official submission of its climate target under Paris Climate Agreement to the United Nations climate body. But that communication only notes the administration used a “bottom-up” emissions modeling approach to assess technology advancements and retirements of aging equipment, and that it reviewed external analyses which “show that the United States can deliver on its” climate goal.

White House officials have praised the process and number crunching led by national climate adviser Gina McCarthy’s office that went in to building the target, and they said McCarthy’s office met with a diverse range of interests that included the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, electric utilities and the American Petroleum Institute. But White House spokesperson Vedant Patel declined to provide any details on the models used to create the targets, and said in an email “we don’t have anything to share that’s reporter-facing on this at the moment.”

Even as Republican detractors float bogus claims that the president’s climate target would force Americans to give up hamburgers, Biden’s defenders suggest there’s good political reason for the White House not to reveal its arithmetic: Giving such details would open the administration up to political scrutiny about whether its models are realistic, hamstringing its broader policy actions to down greenhouse gases.

“If you put out an analysis, you’re immediately debating the analysis rather than policies to reduce emissions,” said one Democratic congressional aide. Still, offering more details would shut down some of the criticisms, the person said. “I will guarantee you they are not assuming we ban red meat or air travel, so I guess in that sense it would answer some issues that are out there.”

The White House hosted months of meetings with a range of groups, including trade associations and climate modelers who presented opposing views on whether a 50 percent reduction by 2030 was realistic.

Environmental groups and world leaders have cheered Biden’s target, saying it provided much-needed momentum to galvanize action ahead of pivotal November climate talks in Glasgow, Scotland. In the run up to that event, the U.S. and others are prodding nations to increase their ambition to keep planetary warming of 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels within reach.

“President Biden has met the moment and the urgency that the climate crisis demands,” Nat Keohane, senior vice president for climate at the Environmental Defense Fund, said in a statement after Biden released the climate target, saying it “aligns with what the science says is necessary to put the world on the path to a safer climate, and vaults the U.S. into the top tier of world leaders on climate ambition. And it’s backed up by numerous analyses demonstrating that it can be met through multiple pathways using existing technologies.”

But industry representatives and Republicans have charged the White House process did not follow a typical consultation. They alleged the administration picked the 50 percent goal to appease environmental allies who said failing to hit that goal would fall short of heeding scientists’ warnings of what’s needed to keep global temperatures from crossing a dangerous precipice.

“The president’s scheme will cost working families a fortune in higher energy bills. It will also hurt America’s international competitiveness,” Sen. John Barrasso of Wyoming, the top Republican on the Energy and Natural Resources Committee, said in a statement. “It’s no wonder President Biden won’t explain to the American people just how much his plan is going to cost them.”

Biden and other administration officials have said developing the technologies and industries to transition the U.S. to a clean energy economy will reap economic benefits, create new jobs and make the country more competitive with rivals like China.

White House officials met with a number of organizations that had performed their own modeling suggesting the 50 percent reduction was achievable, such as Rhodium Group, the Mike Bloomberg-led America’s Pledge and environmental group Environmental Defense Fund.

Administration officials contend they will share more about how it arrived at its climate figure in the future.

EPA Administrator Michael Regan said Wednesday during a Senate Environment and Public Works hearing that EPA projected the emissions it could reduce through “non-regulatory and regulatory programs” like tailpipe emissions standards for vehicles and the EPA Energy Star program for appliances. Regan said he believed EPA could make those estimated emissions reductions publicly available.

“I think the information that we generated conceptually on where these regulations might land within a range, that information can be made available,” he said.

And Jonathan Pershing, who has a lead role on special climate envoy John Kerry’s team, said during a Monday event that last week’s two-day Leaders Summit on Climate was simply the wrong forum to disclose details about how the target would be met.

“There’s been a lot of modeling done there’s an extensive interagency process that’s been convened, that will be forthcoming,” Pershing said. “There will be a great deal more detail, there will be sectoral information, there will be policy by agency, there will be policy in terms of both national programs as well as state programs and those do roll up to be a compelling collective agenda to achieve the target we’ve set.”

Alex Guillén and Matthew Choi contributed to this report