John Podesta, who led the Obama administration climate strategy and is close to Biden’s team, said the White House would need some “diplomatic choreography” if its plan is to work.

The U.S. move “leaves China isolated. The pressure will build on China to stop its coal finance and to green the Belt and Road Initiative,” he said.

But the plan will require the Biden team to closely coordinate its foreign policy, trade and clean energy initiatives, because the absence of U.S. money for coal projects won’t on its own sway other nations’ energy plans. And the U.S. cannot unilaterally offer sweet enough financial terms for clean energy to lure countries away from China’s coal finance.

To outmaneuver Beijing, the U.S. will need to build support with other nations and international institutions to increase their joint financing for green projects, according to a Biden administration official who asked for anonymity because the person was not authorized to speak to the media.

“To be successful, we need to meet China on the field of Belt and Road, and you put together packages with partners that are non-fossil,” the official said. “We’ll have to look at the investment opportunities here country by country by country.

Even as it targets coal projects, the Biden administration is unlikely to seek a blanket ban on funding for projects using natural gas, a fossil fuel that is generally cleaner than coal and has seen its U.S. production and use boom in the past decade. The language in Biden’s executive order calls for a review of “carbon-intensive” projects, allowing leeway for U.S. natural gas exporters to continue their growth — a move Biden officials such as Energy Secretary nominee Jennifer Granholm has touted as keeping countries from pursuing coal projects, and offering allies an alternative to Russian gas supplies.

Determining how any such exemptions work will involve striking a consensus among officials at the White House, Treasury Department, State Department and DOE, said Nikos Tsafos, deputy director of the Center for Strategic and International Studies energy security and climate change program.

“That’s where I think it’s going to get harder to figure out how narrowly or broadly to write the rules,” he said.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen will also be heavily involved. The Treasury oversees U.S. financing agencies like the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, and Yellen has the power to direct how U.S. representatives at the World Bank and other multilateral development banks vote.

Yellen could revive the Obama-era efforts to push back globally through the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development on aid provided by governments to make their exports more competitive, this time with a particular focus on fossil fuels, since much of China’s coal financing relies on that type of government support.

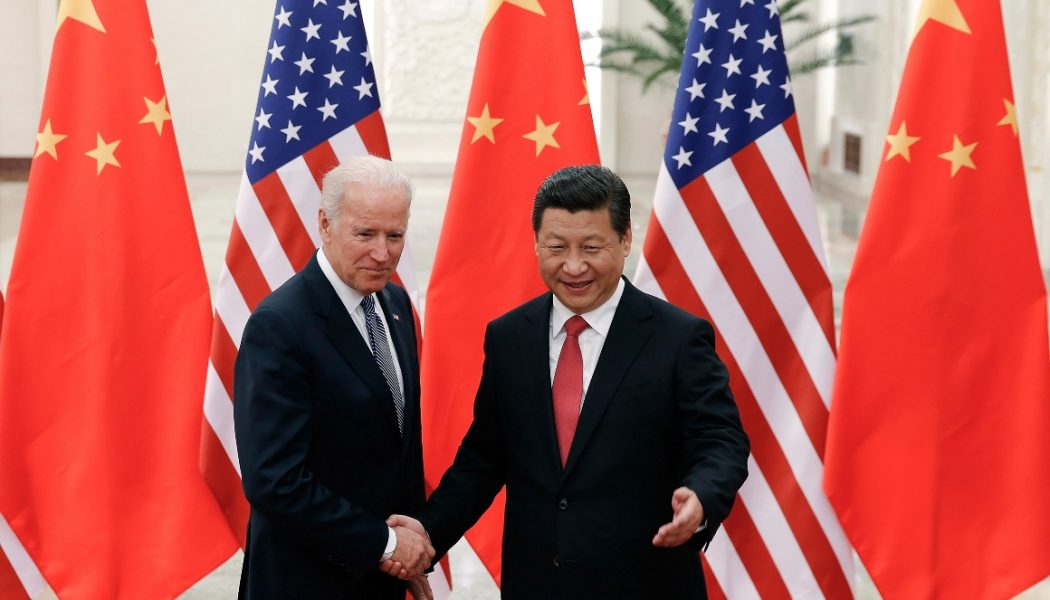

Secretary of State Antony Blinken has said the U.S. must push countries away from “dirty” energy. But how exactly Blinken and White House climate envoy John Kerry will weave the climate agenda into broader foreign policy priorities is not yet clear. In a phone call between Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping on Wednesday, Biden raised concerns about military and economic issues, but also cited areas for partnership, including climate change.

Kerry is expected to try to keep the climate issue at the top of the agenda. Still, it’s notable that Biden has not yet nominated an undersecretary for State’s energy division, said David Goldwyn, a consultant who led State Department energy diplomacy during the Obama administration. That suggests to Goldwyn that Biden feels Kerry is capable of handling many of that department’s duties, which includes energy diplomacy and international economic growth.

China might already be subtly presenting a window of opportunity for Kerry, Blinken and Yellen.

Belt and Road Initiative coal finance fell last year during the pandemic, while declining renewable power costs have made new coal-fired power plants less attractive in places like southeast India. A recent China central government report also criticized alleged malpractice within China’s National Energy Administration, which observers said could bode poorly for coal.

Kelly Sims Gallagher, who handled the Obama White House’s Chinese climate portfolio, said pandemic recovery packages in the EU and now the U.S. are leaning on clean energy growth — and the countries could press China to get behind similar measures.

“It could mean that China is retrenching and rethinking. So bringing China to the table and rethinking about greening the [Belt and Road Initiative] is wise,” said Sims, who now leads the climate policy lab at Tufts University’s Fletcher School.

The U.S. will need to pressure China to end coal financing separately from other thorny issues like trade, intellectual property theft and human rights, said David Sandalow, who was assistant secretary for international affairs at DOE during the Obama administration and served on Clinton’s National Security Council.

“The U.S. government needs to be clear that we think climate cooperation is both in the interest of our nations and the world,” said Sandalow, who is now at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs.

So far, China’s foreign ministry has scoffed at such a separation. It issued a statement on Jan. 28 denouncing Blinken’s characterization of China’s treatment of Uighur Muslims as “genocide” by saying climate change “cooperation cannot stand unaffected by the overall China-U.S. relations. It is impossible to ask for China’s support in global affairs while interfering in its domestic affairs and undermining its interests.”

That could indicate efforts to persuade China to stop pushing coal projects may need to be a long-term effort. But the U.S. could immediately start shifting billions of dollars away from fossil energy if Yellen directs U.S. representatives at the World Bank and other multilateral funders to vote against coal, said Joe Thwaites, an associate with the World Resources Institute’s Sustainable Finance Center.

The number of coal projects funded by those institutions has already dwindled, due in part to efforts under the Obama administration, though multilateral development banks in which the U.S. is a shareholder accounted for $69.5 billion of fossil fuel finance between 2008 and 2019, according to environmental group Oil Change International. Banks where the U.S. isn’t a shareholder — including the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, where China is a major player — approved $53.4 billion of such finance over that same period.

“It’s going to be a big job for John Kerry to try to win cooperation from China and from the Asian Investment Infrastructure Bank,” said Goldwyn, the former State Department official.

Oil Change International said U.S. finance for fossil fuels at the federal government’s Export-Import Bank, the Development Finance Corp. and Millennium Challenge Corp. totaled $48.3 billion between 2008 and 2019.

Treasury could reorient the funding through the Development Finance Corporation — which has a $60 billion authorization — and the Millennium Challenge Corporation toward green technology and infrastructure. And it could step in to help early stage technology deployment the private sector usually avoids, Sandalow said. The Export-Import Bank, an independent agency that assists small and medium U.S. exporters, could further pare back its fossil fuel financing in response to Biden’s climate push.

Ex-Im’s portfolio last year accounted for $12 billion of oil and gas projects, though it’s unclear how much it could help push renewables because much of that equipment is imported and would run up against U.S. content requirements. The agency did not respond to a request for comment.

U.S. efforts to clean up global energy finance could go even further if Washington and Beijing work together to redirect some of the fossil fuel finance already flowing to China’s trading partners, said Joanna Lewis, director of the Science, Technology and International Affairs program at Georgetown University.

“We should also consider constructing parallel bilateral efforts with China in these countries to leverage and redirect Chinese investments toward greener technologies,” she said,

For now, the prospects for cooperation with China appear better on climate than other issues. Biden and his deputies have taken a tough rhetorical line against Beijing’s trade practices and human rights abuses. But Kerry has said he’s determined to separate climate negotiations from those disputes, calling it a “critical standalone issue that we have to deal on” at the executive order unveiling last month.

White House climate veterans say the two sides will need to work together if the worst consequences of global warming are to be averted. That could start with addressing the dirtiest sources of energy worldwide.

“First things first — let’s get a global ban on overseas development on new coal-fired power,” Podesta said. “If they can get that done in the near-term, that would be a significant achievement.”

Victoria Guida and Gavin Bade contributed to this report.