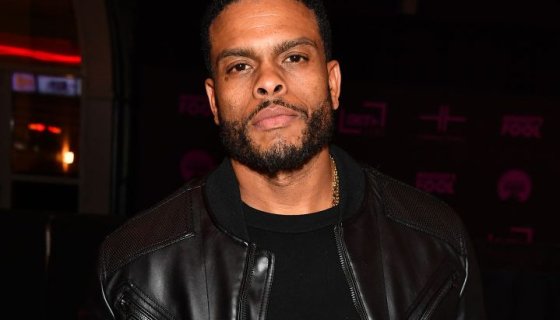

Source: Paras Griffin / Getty

Filmmaker Benny Boom is well-versed in what it means to find camaraderie by way of shared experiences, even 30 years later. Recently, he celebrated the release of his latest collaborative work Tazmanian Devil with fellow Alpha Phi Alpha member Solomon Onita Jr.

Houston-born, Dallas-bred Onita is the writer and director of Tazmanian—out now, available to purchase or rent via Amazon Prime—which tells the story of a young Nigerian immigrant, Dayo (played by Abraham Attah), who moves to Arlington, TX to live with his overbearing father while attending college. He ends up finding solace and hard-earned acceptance while pledging to the fictional Black fraternity Tau Alpha Zeta, or TAZ.

Black boys are often thought of as “grown men” outside of our communities as soon as their shoulders begin to spread — by the time they get to college, the onus is on them to figure out what type of man they want to become. And some may be lucky enough to go through the process, linking up with an adopted brotherhood along the way.

Here, Benny Boom talks about pledging Alpha in the ‘90s, bringing Birdman in as an executive producer on Tazmanian and giving Solomon ample room to cook.

Hip-Hop Wired: Tazmanian Devil is really well layered, so I took down some key points. Let me know if I missed anything…

— Becoming the type of man that you want to be — on your own terms.

— The culture shock that immigrants and sometimes first-generation Americans experience while in college.

— Hypocrisy within Christianity especially as it relates to Black people.

Benny Boom: Sure, sure. Those are three things that I think run throughout the film and the interesting thing is that it reads on the page the same way you see it on film. Weaving all those ideas together into one cohesive thing.

“I was apprehensive at first about the hazing in the film and how other people would accept it but I think I read it three times and on that third time I was like, ‘Man, this is not a movie about hazing. It’s a movie about the rite of passage of a kid.’”—Benny Boom

The thing that I think can be especially appreciated about this film is that it’s about more than just what happens on college grounds. It’s not like a Drumline, no shade to that movie.

There were a few different levels but I think, too, all of those films whether it’s Drumline or Stomp the Yard, those films have taken a different perspective on what college life is like and this is more of a story of immigration, assimilation… It’s a story about how we, as Black people in the diaspora or how Africans in the diaspora, look at Africans. And how sometimes we accept or don’t accept them.

But another level is just the family dynamic. In the film, every time Dayo sees his father it’s at a very pivotal point in his life. Whether it was 12 years old or five years old, it’s those pivotal moments… And the father comes and goes so it leaves him wanting, until he’s old enough to go and live with his dad and he realizes that all these moments are not really what or who this man is.

He had no idea but he realizes that he’s gotten himself into a situation that he didn’t anticipate. His father isn’t as loving overall as he is in those short moments, so now Dayo goes looking for that fatherhood and the friendship and all that stuff in this community that he’s trying to fit into but he’s also looking for a surrogate. And that’s what drives him to pledge and become a member of Tau Alpha Zeta.

There’s a line in there where Dayo says: “I’ve been trying to become a man that I never knew.” Mindblowing.

Yeah. It’s some deep stuff in there and even the faith-based part of the movie… One of the things I applaud Solomon for is, and this is the one thing I say about filmmaking: you gotta be brave to be a great filmmaker and that’s the choices you make in writing, shooting and the scenes. I think that there can be pushback from the faith community about this pastor who’s devoted his whole life to living the missionary life but then has a mistress. But can we say that’s never happened though? We can’t say that’s never happened. But it’s not an indictment on the whole.

And I think that us in the Black community, we indict everybody all the time, for everything ‘wrong,’ when in fact, each situation is different so in this specific situation, it’s just another layer for Dayo to see, ‘This man really isn’t living up to what I thought he was, so now I need to be my own man and have my own ethics and moral compass. I can’t go by his.’ And part of that is him going through this pledge process and going through the brotherhood.

Both you and Solomon are members of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc. Did you discuss how much has changed since you pledged while making this movie?

I pledged about 20 years before Solomon and I would say, just on the record, that Alpha Phi Alpha doesn’t condone any type of hazing of any sort. So this film is just a representation of what we know hazing to be like. It’s not a representation of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Incorporated’s process. But these types of things happen across the board. And in the film, these things happen to Dayo particularly, but it’s not an indictment on all Black Greek Letter organizations or how members are made.

But in that, we spoke about the pledging and the repercussions of putting that up on the screen and the blowback. But again, that’s another strong, brave choice as a filmmaker. When you do those things, you have to say, “You know what? I’m not worried about that. I just wanna tell the story the way the story should be told.” I think it’s important that Dayo went through the hazing in this film. It’s a real outlet for him from what he’s getting at home. He’ll stand there and take the hazing because he realizes that’s gonna take him further away from where his father wants him to be and his father wants to recreate him in his image? He doesn’t want to be that. So the hazing is the rite of passage that he’s willing to go through to completely disconnect from what his father wants him to be. So he needs that.

How much of the pledging process would be too much to show on film?

That’s interesting. I think it depends on where you stand. I pledged 30 years ago so I can’t equate what I went through to what someone is going through in 2021. Also, now I’m an alumni brother so i’m very active in the alumni chapter so my viewpoint on me pledging at 19 years old is very different from now regarding membership but I do think that there’s a rite of passage that needs to happen because there are a lot of responsibilities that come with becoming an Alpha after you cross, within the Black community.

And so when you wear those letters after becoming an Alpha, or a Kappa, or a Sigma or a Que or an AKA or any of those things, it’s very important that when you say that, there’s an expectation placed upon you. And if you haven’t gone through certain things, or been indoctrinated in a certain way, you’re supposed to present yourself in public and within the Black community and if you’re not doing that, then I think you’re falling short. That’s the purpose of a proper pledge process. So what I went through in 1991 is definitely [different] from what the kids are going through in 2021, but it needs to be different, because they have different challenges and different expectations.

How did you and Solomon connect on the movie?

You know it’s interesting. I have a company with a frat brother of mine named Gerald Rawles who’s also produced on the film [Groundwurk Studios]. We get scripts and phone calls all the time and this script came through Tricia Woodgett, another producer on the film. She got us the script and Gerald and I read it. I was apprehensive at first about the hazing in the film and how other people would accept it but I think I read it three times and on that third time I was like, ‘Man, this is not a movie about hazing. It’s a movie about the rite of passage of a kid.’

Like, you can imagine college isn’t a part of it and it’s about Dayo living with his dad and he met some Crips on the street or Gangsta Disciples or something like that fill in. And he seeks entry into that organization and would have gone through similar things because he didn’t want to be like his dad, he wanted to be something different and wanted to fit in. And that’s really the core of what this story’s about. The choices that African American men have to make in these days and times and what to do with those choices.

What key things did you learn while directing All Eyez on Me that you brought with you to Tazmanian Devil?

Well, support is the real key thing. One thing I wanted to make sure that Solomon had for his first feature film was the support of somebody with experience that wasn’t going to get in the way of his vision. It was never my intention when I got involved, to step on Solomon’s vision. I wanted him to get his vision across and if there was any time where he felt like that was being hindered, like, how should something come across or what should he do, then I was there to answer those questions or make those things happen.

So for example, Birdman got involved with the film because the financing had run out and it was my responsibility as the executive producer, to find that money and so I called Birdman and sent him a snippet of the trailer that we’d cut at the time. The shooting had been done and we were on to the editing process. And probably within the time it took for him to see the trailer, he hit me back and said, “I’m in. Whatchu need from me?” I thought that was really amazing how he came through. He loved the trailer but he really loved the idea that I was giving another young Black man the opportunity that I got. That was the other part that really drove him to get involved with the film and put his money behind it. Because he saw what I was trying to do and he wanted to support that as much as he wanted to support a new filmmaker.

Sum up what you hope people take from Tazmanian Devil after viewing.

I hope that people see this film and understand the importance of the family dynamic and the responsibility that fathers and mothers have to their sons and daughters. So the community is aware of what we’re up against in these days and times and that within this ever changing landscape, we have a strong family dynamic. When Black people had nothing but each other., it feels like the unit was stronger. But now, it feels like, the more we “get,” the weaker our unit gets. That’s what I want people to take from it.

HipHopWired Radio

Our staff has picked their favorite stations, take a listen…