A joke by a Chinese stand-up comedian seen to be ridiculing the military has prompted a crackdown on the country’s booming comedy scene. But it hasn’t stopped there. Music performances are now being targeted, hitting the country’s live entertainment sector just as it recovers from years of Covid restrictions. The BBC’s China correspondent Stephen McDonell reports from Beijing.

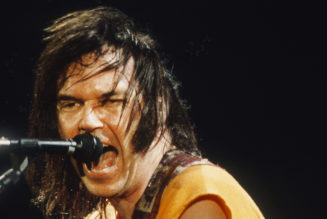

The mosh pit expands and contracts with bodies crashing into one another.

What might appear violent and aggressive is actually a friendly, high-spirited celebration of music and collective enjoyment.

After years spent waiting to shake off China’s Covid restrictions, there are smiles all round.

Relief. Fun. Hilarity.

A friend passes me a drink just as the human wave approaches and I get dragged in, spraying the contents of my cup over all those around me. Nobody cares. It only adds to the desired chaos. It’s a hot evening and we’ll all dry off quickly.

In a country where cultural events are closely monitored by the Communist Party, the underground music scene in the capital has remained energetic, real, cheeky and innovative. It’s a world, for the most part, beyond the grasp of dullard officials.

A venue owner once told me about a visit he’d had from a local government representative who looked around the area at the front of the stage and asked where the tables and chairs were.

The owner tried to explain that the customers preferred to make do without them.

He told me he could almost see the cogs turning in the official’s brain: they… don’t… want to sit down… why… what?

Beijing has always been at the heart of this vibrant scene. Every sneaker-staring, guitar-hugging kid with a broody set of love songs who wants to stand up and play, drifts into this city.

Higher rents and gentrification were already posing great challenges before three years of tough Covid restrictions put some venues out of business. But after the government suddenly abandoned its zero-Covid policy, the music came back quickly.

Audiences couldn’t wait for some live sound again, the bands were up for performing and the bars were certainly eager to make money to pay the bills.

All was looking up until Li Haoshi, a stand-up comedian, told a now notorious joke.

During his live act, he described two dogs chasing a squirrel and said they should “adopt a good style of work” in order to “fight and win battles”. It was an expression which Chinese leader Xi Jinping has used to praise the People’s Liberation Army.

Audio of the joke was published on social media and subsequently weaponised by ultra-nationalists who even targeted the audience for laughing at it.

Li was detained. His contract had already been terminated after his employers, Xiaoguo Culture, were handed a massive fine.

He is expected to receive a prison sentence after police said they’d opened an official investigation into his routine which – in their words – had “caused a severe social impact”.

China’s most famous comedy company has had its shows suspended in Beijing and Shanghai, and there are fears that venues won’t want to book stand-up shows in the future because of the risk it now entails. Word has clearly gone out that comedy performances should be controlled.

But some officials have decided that this also means all performances deemed too potentially edgy, need to be reined in as well. This has led to a crackdown on live music.

Bars and cafes without the correct permits to host live events are in the sights of inspectors. Foreigners who play in bands without specific live performance visas are getting into trouble.

Ever since workers from overseas were allowed into China, as the country re-opened, some of them have played music on the side, say in jazz bands.

Apart from the obvious enjoyment in doing this, it has also been their way of giving something back to a city they’ve come to know and love.

That over-zealous officials would go after Beijing’s non-credentialed saxophonists is seen as absurd by most locals.

The problem is that those making the decisions here are keen to be seen to be imposing the Party’s will more enthusiastically than rival bureaucrats.

However, their motives are not the most important consideration for those in the music industry. All that matters is how long this crackdown might last, and what needs to be done in the meantime.

There’s a simple answer: they don’t know how long this will go on and so, for the time being, they will keep their heads down.

One venue owner laughed at the idea that he would go even on the record about this: “Why would anyone speak to you about it in front of a microphone? I wouldn’t,” he said to me.

In the past, the fine arts have also been targeted in such crackdowns. The inspectors would enter a gallery, point to a few works and say, “they’ve got to come down”. Those pieces would go out the back and the gallery would live to fight another day.

In recent years, artists have also been kicked out of the country and now galleries have to be more careful with what might be seen as provocative or potentially politically sensitive.

Musicians too have to be more careful.

I once heard the lead singer of a punk band declare, in English, on stage, that the Communist Party is the mafia.

A long “woooo” could be heard around the room amid the laughter. But hearing sentiments like that expressed is rare.

For the most part, bands are singing about love and breaking up or the search for meaning in this complicated world.

For now – at least at the venues with all their paperwork in order – performances are continuing.

So, as long as the music is playing, the punks and indie rockers will keep meandering into the hutongs – Beijing’s narrow alleyways.

They will be hoping that this is merely a speed bump rather than a growing threat to one of the best things about modern culture in China’s ancient capital.

Read more of our coverage on China