It used to be that consumers never really cared how they accessed their favorite entertainment just as long as they could.

Bootlegged blockbusters, still raking in millions at the movie theater, often came directly to them in plastic bags for cheap at the barbershop or hair salon. The hottest music could be downloaded onto their computers, compliments of sites like Napster or Limewire. Concerts were affordable even for young people with $6-an-hour part-time jobs in the late ’90s.

Well, no one cares about access until it’s taken away from them — like when a federal court ruled in 2001 that Napster had to shut down after it was found liable for copyright infringement — or until it becomes a money-devouring complication.

That latter fact was a catalyst for the Department of Justice’s antitrust lawsuit just this year against Live Nation, which owns Ticketmaster, a major ticketing site that reached its pinnacle of disaster after some Swifties tried in vain to get tickets to see their girl perform live in 2022.

We’ve now reached a point when the issue at the core of all of this can’t be ignored: the bureaucratic and often racialized structure of access. That was top of mind while watching “How Music Got Free,” director Alex Stapleton’s thoughtful new docuseries that traces the humble origins and spectacular fallout of music piracy.

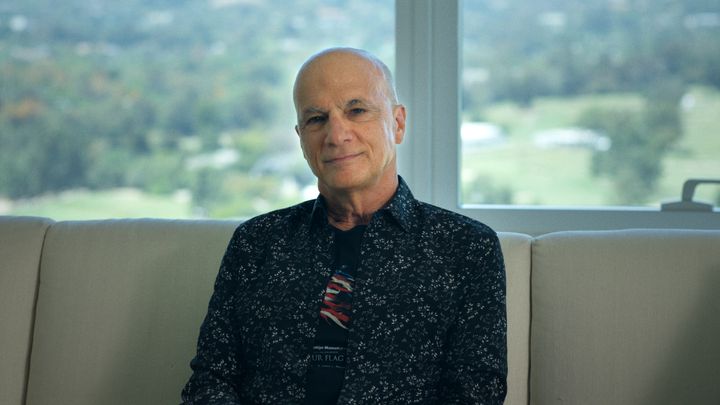

Inspired, in part, by the 2015 New Yorker article “The Man Who Broke the Music Business” by Stephen Witt, who’s also a producer of “How Music Got Free,” the docuseries illuminates the messy, legal and urgent problem of music access. And the series centers the brilliant, and until recently, anonymous Black mind behind it all.

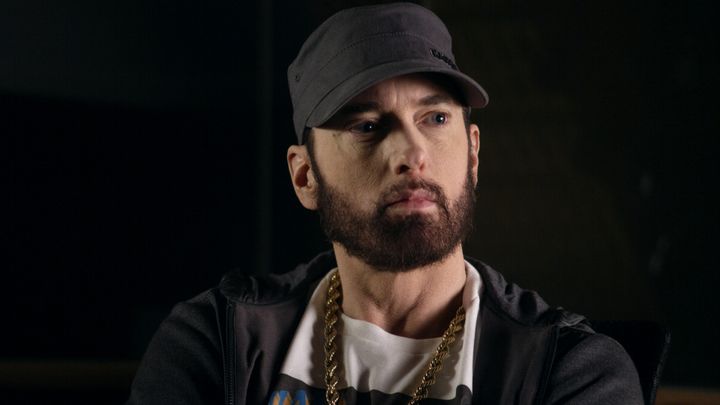

“How Music Got Free” is told through both archival and new interviews with experts, pirates, law officials, artists like Rhymefest and Eminem, record exec Steve Stoute, Interscope co-founder Jimmy Iovine, journalists like Rocsi Diaz, and high-level music marketers at Universal and Interscope.

They help contextualize the story as they still struggle to untangle and reconcile the two-episode series’ pressing themes. I raised its foremost issue of the bureaucracy of accessing music early in a one-hour call with Stapleton. She immediately caught my drift.

“First of all,” the director began, “I think that the bureaucratic nature of the labels and just industry standards is something that we’re always at odds with as both consumers and makers.”

The story at the center of “How Music Got Free” is just one example, Stapleton added. “What we’re in right now with the music industry is where so much of the money is made in touring for artists and live performances,” she said. “Wherever you see that, you’ll see the prices just go up and up and up and up.”

I’ll finish that… and up. For example, premium Taylor Swift tickets can be resold for upwards of $200K, while Beyoncé’s can be at over $1K. To put things into further perspective, the average ticket price in 2000 was $40.74, according to the International Journal of Music Business Research. Even with inflation, that price would only be $74.18 today.

Throughout the late ’90s and early ’00s, the era on which “How I Got Free” mostly reflects, piracy became the perfect solution for fans that just wanted to access their favorite songs at a cheaper price (or totally free), and the perfect problem for recording artists and labels alike.

For context, CDs cost the consumer on average $17, yet around $1 to manufacture at the time for both complicated and “arbitrary” reasons. But this was long before Spotify and Netflix, and before most people were fluent in the internet and MP3 downloading. Pirating was in all intents and purposes illegal. The labels, working with the FBI, saw to that.

With “How I Got Free,” Stapleton argues that that was to the detriment of the industry, particularly because CDs would soon be obsolete and singles were rising in demand.

“What I did want to pick at was this idea of what lengths the industry, or these corporate kinds of places, will go to,” she said. “It’s wild how little they won’t do. They won’t move off the dime. If they’re making money, it’s really hard for them to accept innovation and create change.”

What’s particularly interesting about that presumed threat of piracy, as well as leaks, is that practically everyone was participating in this activity at the time — including Stapleton.

After growing up on Southern hip-hop in Houston, the filmmaker moved to New York City in the ’90s and meticulously selected roommates based on whoever had the best digital music library.

“Because we would share music, you know,” she laughed. “That was a prerequisite.”

Stapleton’s personal contribution was a gold mine. “It wasn’t just hip-hop,” she recalled. “I loved finding weird treasures, like covers of Radiohead or other bands that I really loved. In that period, I loved Luda. Like, love, love, LOVED. And definitely OutKast. ‘Bombs Over Baghdad’ was the Holy Grail moment.”

Much of that music could be heard in “How Music Got Free.” “It was a soundtrack to my life — and it was all pirated,” Stapleton said.

Her love of hip-hop is part of what drew her to the docuseries. Having worked with LeBron James’ production company SpringHill on her 2018 docuseries, “Shut Up and Dribble,” she was looking to collaborate with the team again when executive Philip Byron brought Witt’s article to her attention. “I was hooked,” Stapleton remembered. “Like, instantly.”

She started coming up with ideas after reading Witt’s 2016 book, which bears the same title as the docuseries, that expands on his article — a sprawling investigation of the societal, industry and personal motivations that contributed to the rise and fall of piracy.

“As a Black Southerner, I loved reading a story where at the center of it was this Black guy from Shelby, North Carolina,” Stapleton said. “And it was a hip-hop story.”

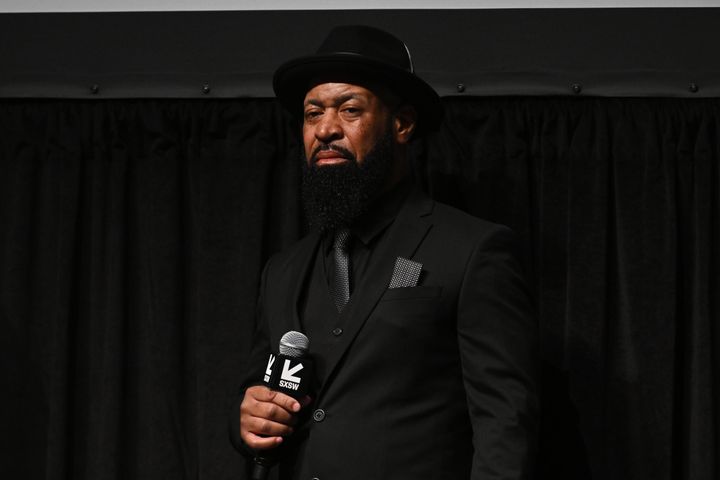

Indeed one of the most fascinating parts about Witt’s story, and Stapleton’s adaptation of it, is Bennie Lydell Glover, a Black, and by most means ordinary, CD plant employee from the tiny town of Shelby.

In the ’90s, Glover began smuggling music out of the plant to a covert online network of pirates. He soon made more money doing that than his full-time job there, and successfully built his own film and music pirating network.

But by the end of the 2000s, Glover, amid an increased crackdown on piracy, was indicted on one count of felony conspiracy to commit copyright infringement and served three months in federal prison.

Navigating multiple setbacks while shooting during the pandemic in 2021, Stapleton traveled to Shelby for interviews with Glover, who appears so disarming even on camera that everyone — no matter their relationship with him — knows him as simply Dell.

With the assistance of Witt, who is also interviewed in the series, the director built enough trust with Glover that he helped her land interviews with people in the area that were close to the story, including other factory workers at the time.

“Dell was an open book,” Stapleton told me.

With Witt’s work as the canvas, Stapleton’s “How Music Got Free” does an impressive job further illustrating the mundanity of Glover’s life and incredible hustle.

“He wanted to provide, like most Americans want to provide for their families,” Stapleton said. “And he had this gift, where he saw an opportunity. That’s very American to be an entrepreneur. Then he got busted — I mean, it was the worst time to be busted with a crime like this.”

Not like any era is really an ideal time to be convicted of a federal crime, but, as Stapleton said, “No one understood.”

Even investigators interviewed in the series scrambled to understand the laws that were being written in real time as more information about the internet and piracy became available to them.

Glover’s story is the heart of “How Music Got Free,” in large part due to Stapleton’s obvious compassion toward him and what he laid the groundwork for, and makes a compelling case for the role of racism in the justice system.

This is a southern Black man with shoddy legal representation, according to his own ponderings in Witt’s article, against multimillion-dollar and mostly white-owned corporations, and alongside mostly white accomplices with often more financial privilege. Glover didn’t stand a chance.

“In the IRL world, he had no access,” Stapleton said. “But on the internet, he was the king maker of access. And I think that there’s something in that.”

She grappled with that a bit before she got to a more pointed question: “How is he any different from Jeff Bezos or Bill Gates or Paul Allen?”

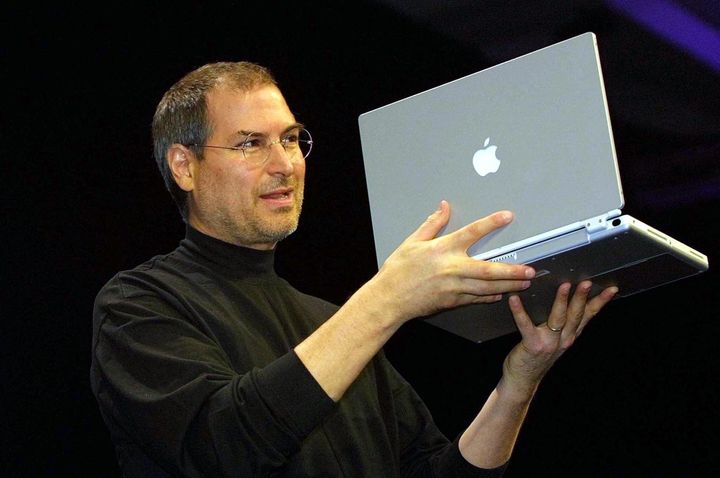

Beyond the obvious racial difference, those white guys — along with Steve Jobs, who Stapleton also mentions — are recognized as technology game changers. Glover, even knowing what we know now, is not.

The Jobs comparison is a critical point for her. Yes, he was an innovator, the director acknowledges. “But what he built was a gateway drug for people,” she said. “The only reason it was successful was because of an illegal activity: piracy.”

That’s a fair point. Both iTunes and the iPod launched in 2001, and most iPod users filled theirs with pirated music.

“The fact that he put a ‘don’t download’ sticker on it and that made it OK is really wild to me,” she continued, adding that that is not a diss at Apple. “It’s more like, let’s look at the inverse negative part of this, which is the guys who proved that the technology worked and helped make you money all went to federal prison.”

Stapleton’s valid insight there is especially striking because much of it isn’t in the docuseries. It is inferred, but there isn’t a voice that really puts this into such a sharp perspective.

While the director admitted that “there were so many other worlds that I would’ve wanted to explore and to have gotten into” had she had more time with the project, the more implicit examination of the role of race and racism in “How Music Got Free” is intentional.

“Some of my past work was very like, ‘I’m going to tell you what I mean,’” Stapleton explained. “Like, ‘Shut Up and Dribble’ or my film about white privilege [‘Hello, Privilege. It’s Me, Chelsea’]. Some people sit down for that. A lot of people just judge the film by the title and won’t sit for it.”

Fair point.

“I thought with this one — it’s very in your face, when you really look at it,” she continued. “I just wanted people to meet Dell where he was. I wanted to trust the audience.”

Still, on a similar point about the role of race, “How I Got Free” does reflect that a large number of pirated music disproportionately impacted Black and/or hip-hop artists.

Part of that is wrapped up in the fact that Universal and Interscope were at their height, and hip-hop, which dominated their catalogs, had a lot of crossover demand particularly from middle American young white guys. That demographic is also represented among most of the pirates.

Stapleton said Witt’s book digs a bit deeper into the hip-hop part of this story and the influence of Universal and Interscope at the time, and she had hoped to do that more in the series as well. But she contextualized all of that a bit more with me.

“The reason why the world got so many leaks that were hip-hop-related was because what kept the lights on at the plant, for the most part, was printing Universal CDs,” she explained. “And specifically, all of Interscope’s artists were printed there.”

This was also around the time when West Coast hip-hop, Dr. Dre especially, blew up.

“The rise in ’92, ’93, when Dre put out ‘The Chronic,’ that was kind of the first album that white kids started to listen to in suburbia,” she said, agreeing with my earlier point. “But it only got bigger and crazier. The numbers were insane.”

While none of the artists interviewed, or even shown in archival footage, were thrilled about their music being pirated, people like 50 Cent, Eminem and Tupac were bigger than ever.

“The piracy wouldn’t have worked if the demand for the music wasn’t there,” Stapleton said.

Sure, but as Eminem says in the series, there are many other people beyond him that need to be paid off one record. A whole team of creatives weren’t considered in the piracy game.

Timbaland, 50 Cent and Eminem all talk about going to extreme measures (Eminem mentioned that he had his team disguise his CDs while still in production, so no one would know what they were), paranoid that they might have been working or were friends with a mole.

Meanwhile, the record labels were trying, and often, to counteract piracy and leaks.

“I think it was a financial thing,” Stapleton said. “But I think from an artistic perspective, it definitely hurt? I can’t imagine people getting rough cuts of my films. I would be mortified. So, I can understand. I think that the debate became very two-dimensional, right?”

Let’s break that down then.

“In the era of Napster and [its founder] Shawn Fanning and all that stuff, it was just, artists make too much money = bad, kids downloading music = good,” she continued. “And even though I will support kids downloading music till the cows come home, it was a lot more complex than that.”

She argued that that would have been the perfect time to have a more complex conversation about what was happening and what needed to happen: “Because we could have potentially figured out some new shit, but nobody really wanted to have that conversation.”

“How Music Got Free,” then, ultimately vindicates the pirates and piracy. How do interviewees including Eminem, who’s also a producer on the series, feel about that?

“He would have to ultimately answer that question,” Stapleton replied. “But I think that all of the artists realize, ‘Damn, if only we had known what the fuck was going on…’ Most were literally too obsessed and freaking out that it was somebody in the studio, someone close to them.”

Stapleton also recognized that Eminem was one of the most leaked artists at that time, and could understand why he was upset. Each of the artists interviewed run a gamut of emotions as the story unravels in the series.

“I think it’s cool and interesting for Eminem to kind of own up and not try to switch the narrative,” Stapleton said. “It was important to show how not cool he was with piracy and leaks.”

That’s real. We’re still grappling with the consumer-artist-corporate entertainment relationship today as at-home technology continues to rapidly evolve. It seems like every day now there’s a new article panicking about the lack of movie theater attendance.

Meanwhile, a single ticket costs on average $20, and it’s likely that the movie will be on a streamer within a month anyway. Or pirated for you to watch somewhere for free.

Stapleton is sensitive to how that all folds into the conversation around consumer access.

“I think the film industry is probably having a really huge reckoning, thanks to technology and everything we learned during COVID, and all the things we can do in a remote situation without having to interface,” she said.

She thought about that some more before adding: “It’s not even so much the streamers right now. It’s the status quo of even other production companies. They just don’t want to change.”

With “How Music Got Free,” she said she’s trying to bring home the point that change remains as inevitable as it ever was, but innovation can still be possible and beneficial.

“When you come to a fork in the road where technology meets art, meets how we receive product, you can get with the program and try to figure it out, or resist and lose out,” she said. “The music industry is still in a fallout period. It’s never going to be the same as it was.”

Stapleton then said this: “And I think that’s good and bad, for artists.”

Sure, because no one, including the artists, wants to lose a nickel on a chance.

“Yeah, absolutely,” she said. “I think what will be interesting is: Will these industries go, ‘Well, we can still be profitable. Our profits won’t be astronomical because that’s not sustainable. But how can we still create things?’”

That’s the crucial question.

“I think that most artists, from people who make music to people who make films to people who write — we want to be paid for what we do,” Stapleton continued. “So that we can put food on the table and support ourselves, for our families or for ourselves.”

Of course.

“We want people to be able to access what we make,” she added. “And I think that these are all questions that I have. How do we all enjoy art but in a way that’s economically viable and fair while still allowing artists not to fall into the trope of the starving artist their whole life?”

The answer to that, even for Stapleton, remains elusive. Or perhaps overlooked, as with the untapped potential of piracy in Glover’s time. “How Music Got Free” makes you sit with that.

“If we’re just having a conversation in an echo chamber with Silicon Valley and the huge corporations and the richest artists of all time,” Stapleton said, “we probably will be missing out on some really interesting and out-of-the-box solutions.”

“How Music Got Free” premieres on Paramount+ June 11.