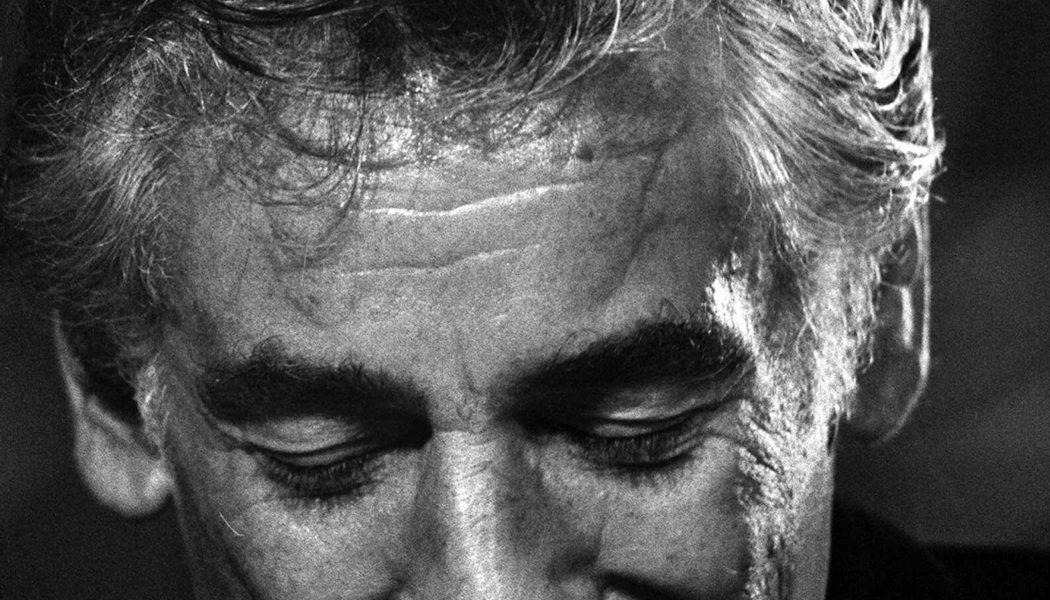

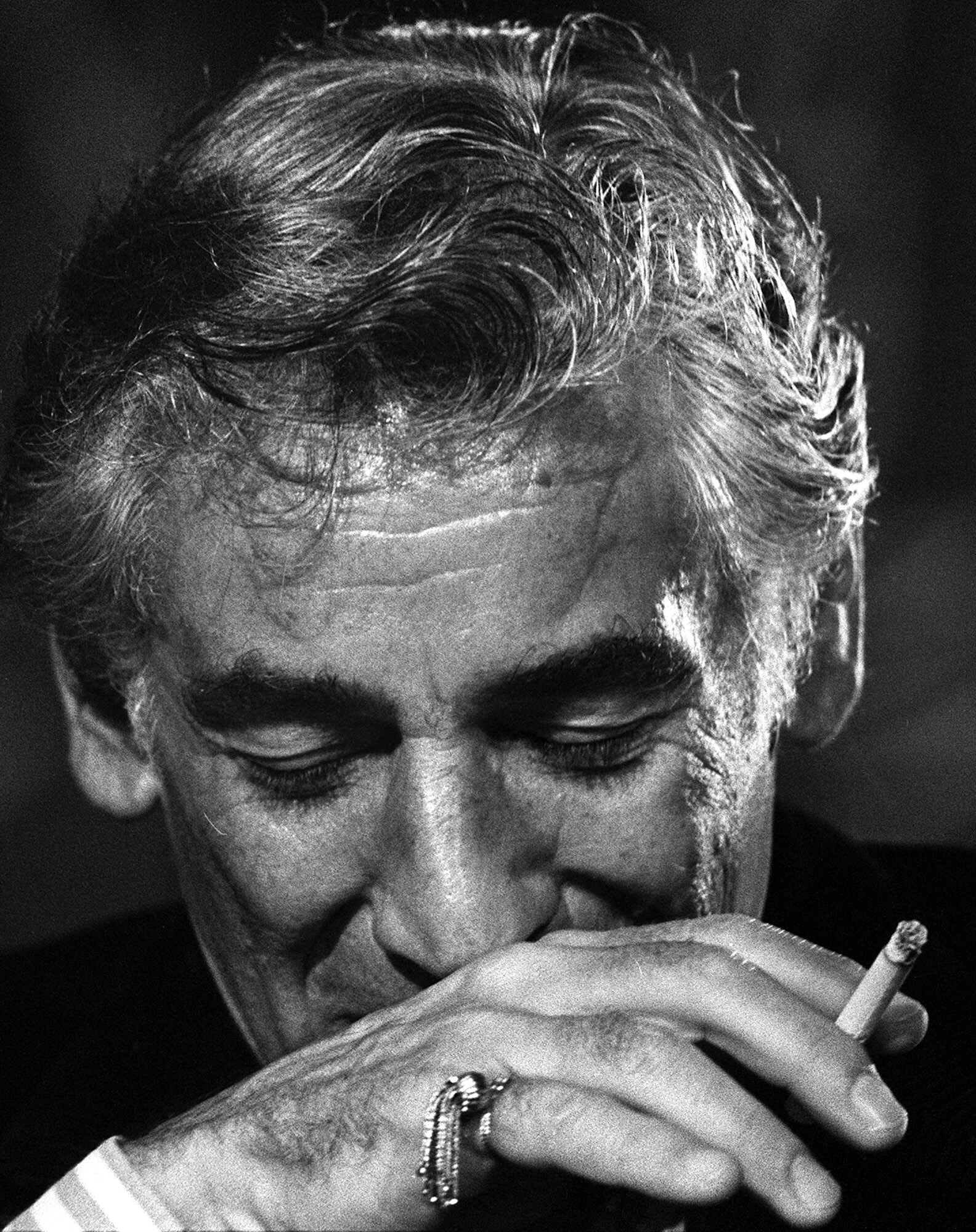

Leonard Bernstein, the acclaimed director and dynamo conductor, is back in the limelight – cast by the recent Netflix biographical film “Maestro,” directed by and starring Bradley Cooper.

Immortalized as the composer of the musical “West Side Story,” Bernstein, who died in 1990 at age 72, was also the best-known conductor in the mid-20th century. Starting in 1958, he was the first American-born and trained conductor of the New York Philharmonic, and he led performances of orchestras around the world – including in Cincinnati.

Some longtime May Festival Chorus members might remember when Bernstein conducted part of the festival’s centennial season in 1973.

At the time, he was one of the most famous classical music figures in the world.

It took two years for Enquirer music critic Gail Stockholm to land an interview with Bernstein. The request came even before controversy arose from the May Festival Chorus performing Bernstein’s “Mass” the year before. (More on that later.)

The reporter and maestro kept missing connections due to his busy schedule. She finally caught up to him in between rehearsals at the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music in May 1973, where he was preparing to conduct Beethoven’s “Missa Solemnis” with the May Festival Chorus and CCM Chamber Choir and Chorale.

Stockholm did her research in The Enquirer archives and found that Bernstein had conducted in Cincinnati three times before in the 1940s.

So, let’s dig in ourselves and see what The Enquirer and Post reported about those earlier concerts.

What Cincinnati said about Leonard Bernstein

Much was written about Bernstein’s rise to fame a few years earlier.

On Nov. 14, 1943, Bernstein was called in on 24 hours’ notice to pinch-hit for conductor Bruno Walter, who had the flu, to conduct the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall with no rehearsal. His debut was broadcast live on the radio across America. At 25 years old, he was the youngest conductor ever to direct the Philharmonic, and he was an overnight sensation.

The much-in-demand Bernstein was invited to be the guest conductor for two concerts of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra on Nov. 2-3, 1945.

Described by The Enquirer as a “triple-threat man of music” – conductor, composer and musician – he clearly impressed the reporters.

Interviews with Bernstein were easier to get in 1945. Enquirer reporter Mary Leighton spoke with him in the auditorium during rehearsal intermission at Music Hall preparing for the performance.

“He had on a sack coat and his hair was tousled,” Leighton wrote. “He has a natural friendliness, but also a business-like manner that makes you know he’s not going to waste any time getting to a pinnacle place in the musical picture.”

About his first concert, she wrote: “Leonard Bernstein created a stir that had something near a cataclysmic effect on yesterday afternoon’s audience at Music Hall …

“Proximity to Mr. Bernstein’s prodigious talent, so amazing in a 27-year-old youth, is almost frightening. And too, his conductorial informality and boyishly modest reception of applause served to heighten enthusiasm for his accomplishments. … He makes listening to music a thrilling experience.”

Bernstein conducted Mozart’s Symphony No. 39 in E Flat and Brahms’ First Symphony, and also performed the piano solo on Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G Minor while directing the orchestra from the keyboard.

Eleanor Bell of the Post wrote: “He played the concerto, one of the more adult compositions for the piano, brilliantly, all the time giving orchestra cues with his head, his eyes and a free hand whenever possible. It was done incredibly well and Mr. Bernstein was too sincere and too able for it to be passed off as a mere stunt.”

Bernstein was even more dynamic on the podium.

“As a conductor Mr. Bernstein was a compelling figure,” Bell added. “He waved no baton, he scarcely glanced at his score. His eyes were everywhere and there were no ‘forgotten men’ … no section of the orchestra went unguided. He literally told each section what he wanted and he got it.”

Bernstein’s popularity was on par with Hollywood movie stars. Bell noted, “The bobby soxers, armed with pencils, swarmed the back-door at the close of the concert.”

The maestro returned Jan. 26-27, 1946, to conduct the CSO in Bach’s “Brandenburg” Concerto No. 5 and Debussy’s “La Mer (The Sea),” while soloing on the piano on Second Symphony in C Major by Robert Schumann.

For his third visit on Jan. 4-5, 1947, Bernstein conducted the “Egmont” Overture by Beethoven and Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony and performed Beethoven’s First Piano Concerto.

According to reviews, the audience brought Bernstein back for six bows after the Beethoven concerto, then five bows after Shostakovich.

What Leonard Bernstein said about the CSO and May Festival

When Bernstein returned to Cincinnati 26 years later, his legend as a conductor was already secure. In his career, he spent 32 years as music director and laureate conductor leading the New York Philharmonic and made more than 400 recordings. His opinion held some weight.

“The Cincinnati Symphony is a whole different orchestra by now, with many new members since I was here last,” he told Gail Stockholm in 1973. “Both the CSO and Music Hall are just wonderful. Members of the orchestra have been extremely co-operative, courteous and perfectly disciplined at rehearsals. It’s a first-class orchestra.”

He had equal praise for the “extraordinary” May Festival Chorus and CCM choirs.

“What I like about the May Festival Chorus is its unique mixture of young and adult sound,” Bernstein said. “When you conduct a university choral group, you usually get an enthusiastic sound lacking the weight of mature voices. When you conduct adult choruses, you usually have the weight without the youthful enthusiasm.

“This chorus combines both of these qualities. The singers are very bright; they assimilate things quickly, and I really gave them a lot, starting with the first rehearsal.

“I can’t help it. It’s a kind of disease with me. If I have a mediocre chorus, possibly I have to make it do. But if I smell the possibility (of) a great performance – as I do here – I get trapped into really working it out.”

Archbishop offended by Bernstein’s ‘Mass’

A year earlier, a warm reception for Bernstein may have been in doubt if he had been on hand when the May Festival Chorus performed Bernstein’s “Mass” in 1972. Some Catholic officials were offended by the work.

Based on the Roman Catholic Tridentine Mass, the theatrical work was composed by Bernstein (along with Broadway composer Stephen Schwartz) at the request of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, the former first lady, for the opening of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C., in September 1971.

According to Brandeis University, “In Bernstein’s setting, he seeks to challenge and question the meaning of the original prayers by inserting tropes, or commentaries, between each movement. The tropes build dramatic tension throughout the work by questioning authority, and by commenting on contemporary issues, in particular the Vietnam War.”

Cincinnati Archbishop Paul F. Leibold wrote a letter to the clergy of the Cincinnati Archdiocese expressing his opinion that Bernstein’s “Mass” was “offensive” because of its use of the sacred elements. “For me, and for most Catholics, his handling of an element that is evidently taken from our most sacred act of worship is in extremely bad taste and offensive to what we hold in great reverence,” Leibold wrote.

Leibold had not seen the production yet, since this was the first performance since the Kennedy Center premiere, but he had read the script.

Cincinnati audiences went anyway. Both May Festival performances at Music Hall were sold out, standing room only. And the audience gave the production an eight-minute ovation.