NORTH ADAMS — How does a body dance oxygen? How does a body dance trees breathing out and people breathing in — the invisible balance that keeps us alive?

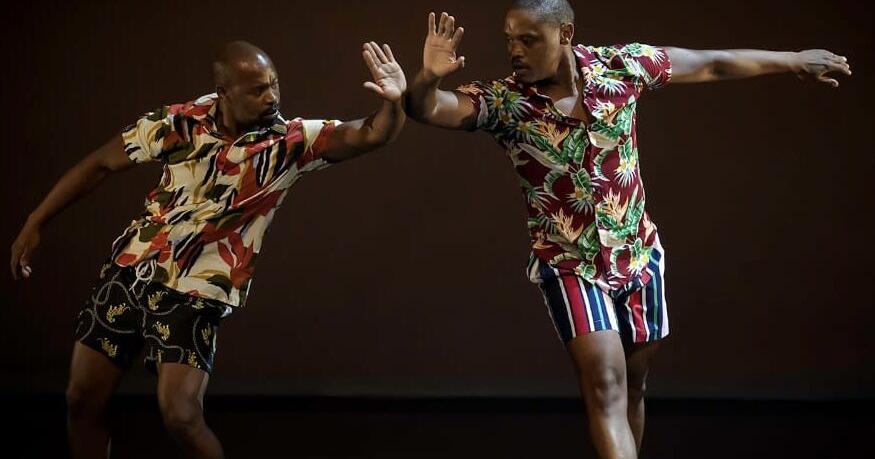

South African choreographers/dancers Thulani Chauke and Albert Fana Tshabalala will find out in North Adams as they improvise together.

They have performed with companies in Soweto and internationally — people in the Berkshires know Chauke as a principal dancer in William Kentridge’s “The Head and the Load,” which was developed at Mass MoCA in 2018, and Tshabalala is artistic director and Chauke’s co-founder of the Johannesburg collective, The Broken Borders Art Project.

Longtime partners in collaboration, they will come to the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art as artists-in-residence supported by Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, and perform a new work, “Eight Elements in Eight Hours,” March 9-11. And they mean the name literally, Chauke said. In this work they will go farther than they have gone before, performing across a full day.

He and Tshabalala will explore the elements of life, he said, speaking by phone from his home in South Africa — they will shape earth and air and water and fire, and shade into the more than 100 elements in the periodic table.

As they embody complex atomic structures, each one feeding from another, they probe the balance of the natural world and a broad perspective on human experience.

“Your pain and my pain may differ in circumstances,” he said, “and yet we can share similar [characteristics]. When we look at how we as human beings are messing up the ozone layer … it all becomes relative. Earth, air, water — nature is affected daily. Our bodies are affected.”

In this kind of improvisation, he and Tshabalala will begin with a substance like earth and a sense of surfaces and textures they imagine moving on and through, how rough or smooth they are, as hard as baked clay or soft as tidal mud.

And the elements can change. They can present more than one aspect. Fire burns, he said, and flames may look translucent and harmless or visceral and stronger than a human frame can stand.

“His movement vocabulary is so beautiful,” said Pamela Tatge, executive and artistic director of Jacob’s Pillow, “and I look forward to seeing how all of the elements will come together to create an immersive experience for audiences.”

She has come to know Thulane’s artistry from his work with Gregory Maqoma, director of Vuyani Dance Theatre, and through “The Head and the Load.”

“It’s exciting to have him in residence at Mass MoCA creating a new work,” she said, and we’re so grateful that he is opening up his process to museum visitors.”

Chauke roots the work in human connection to the natural world. He defines a relationship he feels is deeply important for everyone, he said and especially vital now.

“We are people of the soil,” he said, “and the minute that connection disappears, it’s the end of the human race.”

People need to take care of the earth as the earth takes care of people, he said, and taking care does not need to take much effort — natural cycles can replenish themselves, and natural systems can reproduce themselves, given space and time, as trees and plants breathe in the carbon dioxide people breathe out and give back oxygen to fuel mobile creatures.

Human relationships with the earth can form their own natural cycles, he said, like parents caring for children, and children respecting their parents and the rules of the house.

But people are testing the earth’s physical limits. And in a related vein, Chauke and Fana envision this longform improvisation as a test of their own bodies. They have not performed for eight hours nonstop before, Chauke said, but they have performed for four, in an earlier work called “0.1.”

At that pace, their choreography took on a kind of rhythm in its structure, he said. They found that they would cycle, beginning in one place, one set of movements, and returning to them over time, each time with different energy and intent.

Creating the work as they go, constantly changing, they keep moving onto unexpected ground, and Chauke enjoys the rawness of it.

“Fana and I — in how we treat creation, the creative processes are the performances,” he said. “You’re going to dive into it right there. We’re not rehearsing. … We go in and surprise ourselves. … I like being in vulnerable places, because the creative juice just flows.”

The body has the mind to rely on, and the mind has the body, he said, and this tool, his body, can surprise him in so many ways. He comes into this space to experiment, to play, to test his physical limits and let the performance unfold. Moving in a conscious and subconscious rhythm brings him into places he has never been before, places very different from the depth he can achieve in 90 minutes on stage.

“We started to realize things about ourselves,” he said, “about (the ways we have) bodies accompanying the soul — once we test the waters, cross the boundaries, the limits of what our bodies can carry. … It’s the best space I’ve ever been in, for our entire life.”

They are performing for an audience that can be fluid. At the museum, people can come and go any time, he said. But many people have stayed with them. The French audiences for “0.1” waited until the end.

People who came at the beginning stayed as the piece evolved and the dancers felt their way through, one beat at a time. They would heat up and sweat and cool and raise energy again. Sometimes it felt like being hypnotized, he said. People told him the experience raised questions about their own lives.

And he and and Tshabalala are responding to their audiences as they perform. They are responding to the space, the artwork around them, footsteps and conversations, and what they see and feel, smell and hear.

They are even improvising the music they move with throughout the day. Thulani creates the sound with a fiddle and an electric loop, he explained — he improvises music at home, and he brings his laptop to the performance, plays the music live and makes changes live, even while they are dancing.

The sound can become another surface to reflect the dancers, he said, harsh and rigid and strong when their movement becomes soft and mellow. Movement and sound have a relationship, and they can become intimately close.

“… In Africa, most especially in South Africa, we take our heartbeat as the beat,” he said, “so we always have song and dance and music, and they are always moving together. You can move with the sound created by your heart or the flow of the blood in your body. It depends how in tune your ear is, and how in tune you are with your body, the music playing on the inside.”

He remembers his time in North Adams five years ago, getting up early to call home to his son across the seven-hour time distance.

“In the Head and the Load,” he crossed the full length of the space with a companion — one man bearing pain, bearing weight beyond the limits of his body, almost collapsing, holding himself upright, falling into the man beside him who holds him upright, holding each other.

IF YOU GO

“Eight Elements in Eight Hours”

What: In conjunction with William Kentridge Studios,Thulani Chauke, will be in residence developing a new site-specific durational dance work set in a gallery space. Created in collaboration with Chauke’s fellow South African dancer, Albert Fana Tshabalala, and featuring improvised live music, museum visitors are welcome to come and go throughout the day.

Where: Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, 1040 Mass MoCA Way, North Adams

When: March 9-11

Performances: Daylong. Audience members can come and go as they please.

Museum Hours: 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., Wednesday through Monday.

Admission: Included with museum admission.

Information and tickets: 413-662-2111, massmoca.org