PARIS — Pharrell Williams didn’t get here by chance. Becoming the creative director of Louis Vuitton menswear, he said, was an act of divine intervention. “When God comes through and blindsides you with a blessing that you didn’t see coming, it does something to you,” he said, just a few hours before his debut show in Paris on Tuesday. He was feeling “electrified by excitement,” he said. “Shock and awe.”

Wearing a blue blazer over a white T-shirt and jeans in a pixelated version of Vuitton’s famous damier check that resembled camouflage (which he has deemed “damoflage”), Williams underscored that he is humble. Grateful. And just as surprised to find himself here as the rest of the fashion industry.

After the death in November 2021 of Virgil Abloh, the creative director who permanently recharted the contours of aspiration in luxury fashion, bringing legions of teenage boys along the way, many names popped up in the press as candidates to lead Vuitton. The brand is the crown jewel of the LVMH empire, bringing in a record 20 billion euros (about $22 billion) in revenue last year, and while womenswear, overseen by Nicolas Ghesquière, dominates its sales, its menswear is an influential pop culture force. Williams wasn’t speculated as a candidate, and while he had a longtime relationship with Chanel, and started the streetwear label Icecream in 2003, his appointment was met with ambivalence that a celebrity, no matter how admired his taste, was entering the exclusive realm of fashion designer.

Instead, he was plucked via text by Alexandre Arnault, the 31-year-old son of LVMH kingpin Bernard Arnault who is helping to remake Tiffany & Co. as a cornerstone of millennial culture with Supreme and Nike collabs and a campaign fronted by Jay-Z and Beyoncé. Williams’s appointment speaks not only to the celebrity-fication of fashion, but how the millennial generation thinks about reinvention, creativity, luxury and aspiration.

Williams, 50, talks with a strange and intoxicating mix of pragmatism — speaking fluently and intuitively about the Vuitton customers’ lifestyle and needs — and mysticism. When asked by one reporter whether the show would pay tribute to Abloh, Williams’s answer was lofty yet shrewd. “I collaborated with him on a couple things spiritually,” he began. “He’s up with the stars now, but his energy is still very much… here. There’s a couple SKUs in there where absolutely I have to nod to my brother” — employing the abbreviation for “stock keeping units” that is generally used in nitty-gritty conversations about retail, not runway concepts.

In other words, Williams thinks like a consumer, but one who dreams wildly, the kind of person who walks into a store and says, “But why can’t I have that?” Brands used to rely on celebrities to interpret their wildest fantasies — to make them digestible on the red carpet or concert stage. Williams collapses those two roles into one, as the ultimate evolution of the notion that the customer is always right: The customer is, ultimately, the designer.

Every few years, a show happens that recharts the value system of the fashion world. Its impact is so large that other brands and creative directors copy the textures for seasons to come; it can shift what clothing looks like (down to the goods on Amazon and Shein, where its knockoffs appear), or what 20- or 30-somethings care about. Louis Vuitton, under the creative direction of current Dior menswear head Kim Jones, collaborated with Supreme in 2017, for example, and while that may seem parochial even to casual fashion fans now, this melding of a secretive streetwear brand with the rarefied world of French artisanship was unprecedented, ushering us into an era of collaboration mania.

Then there was the debut of Abloh in the role that Williams now holds, in 2018. That moment was the toppling of fashion as a suite of concepts overseen by White executives who at once looked to the tastes of Black culture for ideas while only begrudgingly acknowledging its people as consumers. Abloh’s show made the runway a yellow brick road and the designer a wowed and mischievous student in a surreal world, asserting that the muse and maker could be one in fashion. That position became a full-throated promotion of the tastes, whims and dreams of Black men in 2020 when Abloh began working with Sierra Leone-born London-based stylist Ib Kamara, who now leads Abloh’s brand Off-White.

Balenciaga’s first couture show, in July 2021, was probably the last such show; since then, runway designers from Prada to Tory Burch have echoed (knowingly or otherwise) its ladylike, mid-century panache.

Williams’s Vuitton debut was just such a show. There were rumors that the Obamas would show up, that Rihanna would perform. The reality wasn’t far from the gossip: We all boarded a boat in the Seine, looking out at a massive billboard outside the Musée d’Orsay featuring Rihanna in Williams’s debut ad for the house . The singer looked like the Statue of Liberty with her coffee cup hoisted in the air like Lady Liberty’s golden lantern. Williams was leading us to a new world of fashion, and Rihanna would light the way!

The boat took us to the Pont Neuf, one of Paris’s most storybook bridges, which was slathered in a honey-gold damier check. The sun began its pink descent, casting the city with a rosy glow as folksy accordion renditions of such Paris classics as “Sous le ciel de Paris” played. It was so vividly, cartoonishly Paris that it almost looked like AI.

Celebrities from Beyoncé and Jay-Z to Rihanna and A$AP Rocky to Zendaya to LeBron James to Tyler, the Creator to Kim Kardashian poured onto the bridge. After the runway show wrapped, I watched Jay-Z perform his biggest hits sandwiched between former British Vogue editor in chief Edward Enninful, Leonardo DiCaprio and Tobey Maguire. It felt more like Graydon Carter’s Oscar party than a fashion show — an experience impossible to merely stream. (Though one can imagine the Arnault family might have a big streaming concept in the cards.) Williams came onstage to accompany Jay-Z for “I Just Wanna Love U,” hitting the falsetto notes with ease.

How many other creative directors of fashion brands can do that? Over the past two decades, fashion and popular culture have come to feel interchangeable, but this was a new degree of closeness. An idea or designer no longer toils as a niche fascination, with a famous musician or powerful editor sometimes making them a star. Everything is for everyone, right away. The celebrity is no longer the person reflecting a culture’s values but creating them.

“The philosophical question that we posed to everyone is, man, when the sun is shining on you, what will you do?” Williams pondered earlier in the day. “I chose to show my appreciation and my love for this opportunity and the idea that someone who looks like me gets to do this again.”

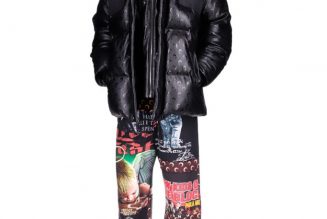

Does Williams have the chops to lead a fashion house? With an atelier as talented as Vuitton’s, it was nearly impossible for him to fail. Still, his clothes were straightforward and commercial, suiting and sportswear that mostly played with the damier check, a print that has made Vuitton a Canal Street mainstay. Like Abloh, Williams’s models looked like archetypes — the banker, the hustler, the student, the fashion nerd — but his buzzed with more obvious desirability than his predecessor’s. He knows his garments and bags are all products. (He spoke effusively about bags, which remain the driver of the luxury business.) His soundtrack, including a cinematic score and a song by Clipse (the brothers Pusha T and No Malice, who also walked the runway) and a gospel song, articulated the Williams approach: a sweeping Hollywood ambition, an appreciation of hip-hop culture, and then “joy, joy, joy.”

He saw the LV logo as “love,” he said. “And the question is, are you a lover of life or are you a lover of details? Are you a lover of expeditions, excursions? And if you are, we’re going to design for that.”

As packed as the show was with celebrities, it was also crammed with clients, the kinds of shoppers whose extravagant purchasing habits are rewarded with an invitation. “You look tired. But you look expensive,” said one woman in a Yayoi Kusama dotted Vuitton bag and pants to another in a pale blue Abloh-designed suit. Another woman kept accidentally thwacking fellow showgoers with an enormous Vuitton bag shaped like an airplane. “We’re all here for the same person!” cried a woman in a Vuitton crop top and gold skirt, as her husband, in a fur Vuitton monogram-print vest, took a selfie. It’s not hard to see a near-future in which the runway clothes are like merch for a fabulous fashion show experience.

Stepping into this new role, Williams feels responsible, he said, to emphasize Black culture, “from pushing the damier all the way to working with a Black American artist, a painter by the name of Henry Taylor.” He embroidered pieces with Taylor’s portraits, replacing some of the LV monograms’ stars and flowers with the faces of Taylor’s friends. “Seeing black faces on here lined up like the monogram — that’s a gift to be able to do that.” But it’s also possible that it’s not so precious — that he is untroubled by commodification of people or identities so long as it is the right identities being commodified by the right creator.

Similar complications arise in the aforementioned ad he released last week featuring Rihanna, her belly exposed alongside an armful of Speedy handbags (the house’s hit bag for nearly two decades). “To have a campaign with one of the biggest icons on the planet who happens to be a Black woman with child, Rihanna,” he said, “it’s not lost on me that I’m afforded this opportunity to tell these stories.”

Ultimately, what Williams’s arrival solidifies is the shift in fashion away from risk-taking to empowerment and affirmation. His own fame was shaped as much by his producing and performing talents as it was by his ability to wear crazy stuff, like an enormous Vivienne Westwood hat or pearls or painted nails. One working definition of fashion is taking a risk over and over, insistently or even obnoxiously, until everyone else gives in and takes the risk too. For Williams, it is about suggesting that a huge corporation respects you and thinks you are powerful.

Is that ominous, or fabulous? Maybe both. As I watched all these dandies and slick travelers and lanky tastemakers, I thought of Wes Anderson — the director whose new film, “Asteroid City,” has been warmly received but whose mannered, gently absurdist style has recently become a TikTok meme.

Anderson is often accused of being too twee, too White, but his films also argue that a well-articulated aesthetic, and a respect for it, is the backbone of humanism. It isn’t that everyone and everything should look the same, but that everyone should be lovely. Beauty is a sign of respect, both for oneself and those around you. (Enemies included.)

As I watched the models flood the runway for the finale — Pusha T and No Malice in coordinating luxe versions of souvenir jackets, designer Stefano Pilati in a white cardigan jacket, men in leather logo-print jogging suits and pearl-encrusted track jackets — it occurred to me that Williams is suggesting that the Louis Vuitton logo is a symbol of civility and gentleness. To wear it, to clad yourself in Williams’s exquisite taste, is to mark yourself as a member of a club committed to graciousness.

The question is not whether Williams can design clothes or make covetable products. He knows better than anyone in the world what to buy and why you should buy it.

Instead, the question is whether Williams can convince the world that a corporate symbol really can mean all that he says it does. Can good taste change the world?

A previous version of this article misstated the song Pharrell Williams performed with Jay-Z. It was “I Just Wanna Love U.” The article has been corrected.