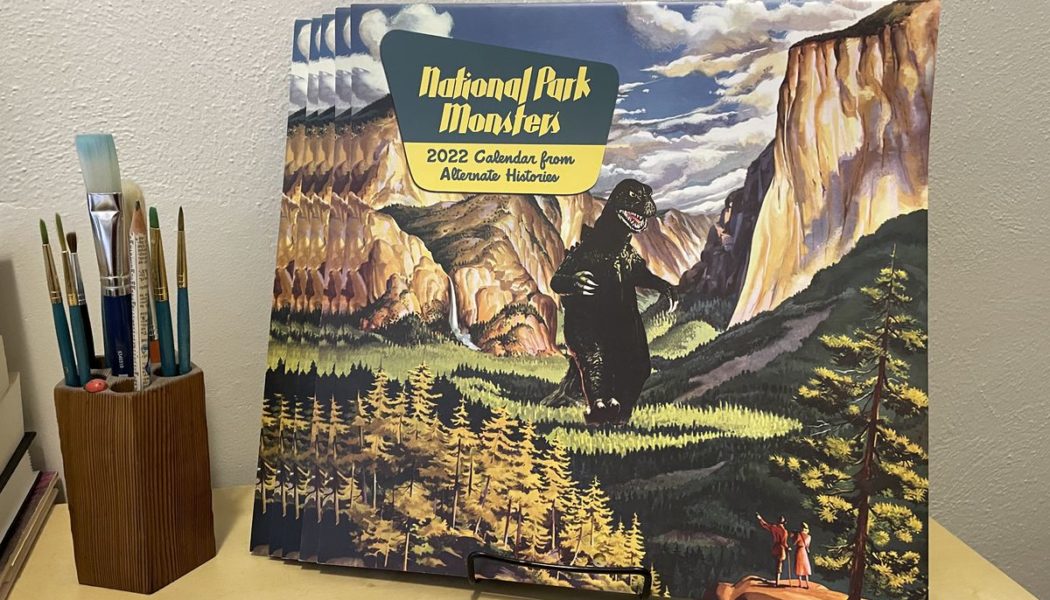

Matt Buchholz’s artwork is usually a hit during the holidays. Under the name Alternate Histories, he creates surreal landscapes of sci-fi staples — think Godzilla or flying saucers — appearing around major cities, which he prints on giftable items like postcards and calendars. But this year, Buchholz found himself with unexpected competitors: counterfeiters ripping off his designs and offering them for sale via Facebook ads.

“Someone sent me a screenshot and was like, ‘Hey, I just saw this ad on Facebook for your calendar’,” he said in an interview with The Verge. The ad had his 2022 calendar and even some of his marketing copy, but the shop wasn’t his. “It had tons of other products that a reverse image search on Google showed were stolen.”

Buchholz is one of the many small sellers overwhelmed with a flood of knockoff and counterfeit versions of their work appearing for sale online. Major platforms allow these fakes to quickly find an audience — he estimates dozens of his work on Facebook alone. And while there are ways to get them taken down, it’s time-consuming to chase down every fake to get it removed, and demoralizing to see ripoffs continue to proliferate across the internet.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23232223/IMG_9319.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23232253/Screen_Shot_2021_12_01_at_12.58.27_PM.png)

“I’m not sleeping well; I wake up to another person tagging me in a post with a new thing like, ‘Oh look, now they’re selling my Christmas card’,” Buchholz said. “It’s been really draining. I’ve really had to kind of push myself to keep going through it.”

To spread their fake goods on platforms like Facebook and Amazon, counterfeiters take advantage of a legal provision that protects those companies from user-generated copyright infringement. Under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), enacted by Congress in 1998, these companies have to cooperate with copyright owners to “expeditiously” remove infringing content posted to their platforms. But there’s often a gap of time between when a listing goes up and when the platform catches the infringement and takes it down. And that gap is often long enough to make the effort worth it for counterfeiters.

“It’s been a little like whack-a-mole,” says Aaron Reynolds, the artist behind Effin’ Birds, a comic series of swearing birds. Merchandising sites can be particularly bad, he said, willing to print anything a user uploads. “Some of the platforms are really scuzzy and they use the protections of the DMCA. They know they can sell bootleg content for like seven days without consequences, as long as they take down the image when a platform orders them to.”

Buchholz says that of the sites where he lists his work for sale, he’s found Etsy to be the most difficult to get infringement problems resolved on. “They use an automated form for complaints, and only allow 255 characters to describe your problem, and there’s no way to appeal their decision,” he said.

Corinne Pavlovic, vice president of trust and safety at Etsy, said in a statement that the platform is committed to protecting creative works. “We comply with applicable intellectual property laws by assessing all reports, removing items when we receive proper notices of infringement and terminating sellers who receive repeat notices of infringement,” Pavlovic told The Verge.

Even people who should be experts in copyright matters can struggle to contend with takedown policies. One semester, Sandra Aistars, director of the Arts and Entertainment Advocacy Clinic at George Mason University, had law students do takedown notices for artists and nonprofits and tracked their interactions. Ideally, websites would take down infringing content as soon as they’ve ascertained it’s fraudulent — but proving something is counterfeit can be a daunting process.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23232287/Amazon_Canada_Effin__Birds_search.jpg)

“The students had all these interactions that are not supposed to happen under the DMCA, with the site operators,” Aistars said in an interview with The Verge. “The site operators would come back at them with, ‘Well, are you really entitled to take this work down? Prove that you are the owner or the agent,’ or whatever, after they’ve presented an affidavit under penalty of perjury to do this.”

The exercise made it easy to understand why an artist or creator without legal training would be intimidated out of sending their own takedown notices — she says even law students were rattled by the pushback. “There are all sorts of obstacles that are thrown up in front of artists who are trying to use the minimal tools afforded to them under the act.”

It’s hard to get a handle on just how much money and content is siphoned away from artists by scam artists online. The Wall Street Journal reported in November that a 2018 internal Facebook analysis found 40 percent of its pages traffic went to pages that stole or recycled most of their content. And that’s just Facebook.

Beyond the lost revenue, Buchholz says he’s worried about damage to his reputation as well. During a recent sweep of Amazon for fakes in late January, he found yet another egregious example of a counterfeit of his work, along with several one-star reviews from angry and disappointed customers. They thought they were buying the authentic Alternate Histories calendars, rather than the knockoffs. One reviewer called the calendar “terrible quality. The printed photos look nothing like the picture advertised and the words are spelled wrong in the text descriptions. The pictures of the creatures are just blobs on a vague, blurred background.” The reviewer encouraged others not to buy the calendars.

People who buy the knockoff calendars often contact Buchholz to complain about the quality, and there’s nothing he can do for them, much to his consternation. “I can’t help but think about how this is irreparably harming my brand,” he said.

Reynolds has also found that bootleg copies of his work often sell at higher prices; a recent fake of one of his T-shirt designs was selling for $30, when he normally sells it for $19. He offers a discount code for people who buy direct from him: FUCKBOOTLEGGERS.

The bigger problem is not the one-off fakes, but the broken system that allows counterfeited works to proliferate with ease on the internet, says University of Akron School of Law professor Mark Schultz. The DMCA, he says, was made for a different era

“One of the big problems with our copyright infrastructure on the internet is it was really designed around what was happening in the mid- to late ’90s, before Napster,” Schultz said in an interview with The Verge. In the olden days of the 1990s, it took a long time to download a file, and the internet was more like a new social network with a small audience, he says.

“The reality at the time was that content didn’t spread fast. So infringement was more like an infection people hoped to quarantine.” But now, Schultz adds, infringement is an endemic problem. “It’s a condition we need to learn to alleviate and reduce, but we’re never going to get rid of it.”

Facebook spokesperson Jen Ridings said the platform has a “robust” takedown program and has invested in “proactive” detection features to support creators’ IP rights. “These measures aren’t perfect, and we know that those who try to abuse our platform will continue to change tactics in their determination to violate the rights of others, which is why we also rely on rights holders to report content they believe infringes their IP rights,” she said.

Amazon didn’t reply to questions from The Verge about how it handles counterfeited products on its platform.

Unofficial Alternate Histories calendars advertised on Facebook. Images: Matt Buchholz

Schultz says he’s testified before Congress twice on copyright issues, once in 2014 before the House and again in 2020 before the Senate. He said he and his colleagues marveled at how little had changed between the two hearings. But, he added, there’s been a greater understanding in recent years of the power imbalance between big tech and the rest of society. “DMCA reform is very tough,” he said.

Aistars said she’s encouraged by a discussion draft that Sen. Thom Tillis (R-NC) introduced in late 2020, seeking to reform the DMCA. “The copyright act is already terribly unwieldy, and you can’t legislate as quickly as people can innovate,” she said. “The things that have held up over time are when you take a technology-neutral approach, and enact provisions based on higher principles, and find ways to get parties to collaborate.”

That’s why Schultz favors a notice and stay-down requirement, meaning once a site has been notified that a work is copyrighted, it has to remove all instances of the work — not just individual files, but all present and future versions. He acknowledges such a system would work better for large entities than for indie creators or smaller platforms. And the Electronic Frontier Foundation has argued that this approach would be more like a “filter-everything” system, and would be too costly for smaller platforms to enforce. But Schultz notes that the European Union made notice and stay-down rules part of its copyright directive, and exempted smaller startups to prevent the rule from being too onerous.

For his part, Buchholz says he thinks there are a few simple things platforms can do to reduce the amount of counterfeiting they are unintentionally supporting, like offering systems to verify sellers as genuine. And Aistars says platforms should make the tools they already offer to more powerful entities like the NFL, which can get pirated football game footage taken down quickly from major sites, more readily available to other creators.

“The tech is there to police these things,” Buchholz said. “It’s just a matter of making it available to anyone who posts work on the internet. But I don’t know if they ever will.”