Apple stakes its reputation on privacy. The company has promoted encrypted messaging across its ecosystem, encouraged limits on how mobile apps can gather data, and fought law enforcement agencies looking for user records. For the past week, though, Apple has been fighting accusations that its upcoming iOS and iPadOS release will weaken user privacy.

The debate stems from an announcement Apple made on Thursday. In theory, the idea is pretty simple: Apple wants to fight child sexual abuse, and it’s taking more steps to find and stop it. But critics say Apple’s strategy could weaken users’ control over their own phones, leaving them reliant on Apple’s promise that it won’t abuse its power. And Apple’s response has highlighted just how complicated — and sometimes downright confounding — the conversation really is.

What did Apple announce last week?

Apple has announced three changes that will roll out later this year — all related to curbing child sexual abuse but targeting different apps with different feature sets.

The first change affects Apple’s Search app and Siri. If a user searches for topics related to child sexual abuse, Apple will direct them to resources for reporting it or getting help with an attraction to it. That’s rolling out later this year on iOS 15, watchOS 8, iPadOS 15, and macOS Monterey, and it’s largely uncontroversial.

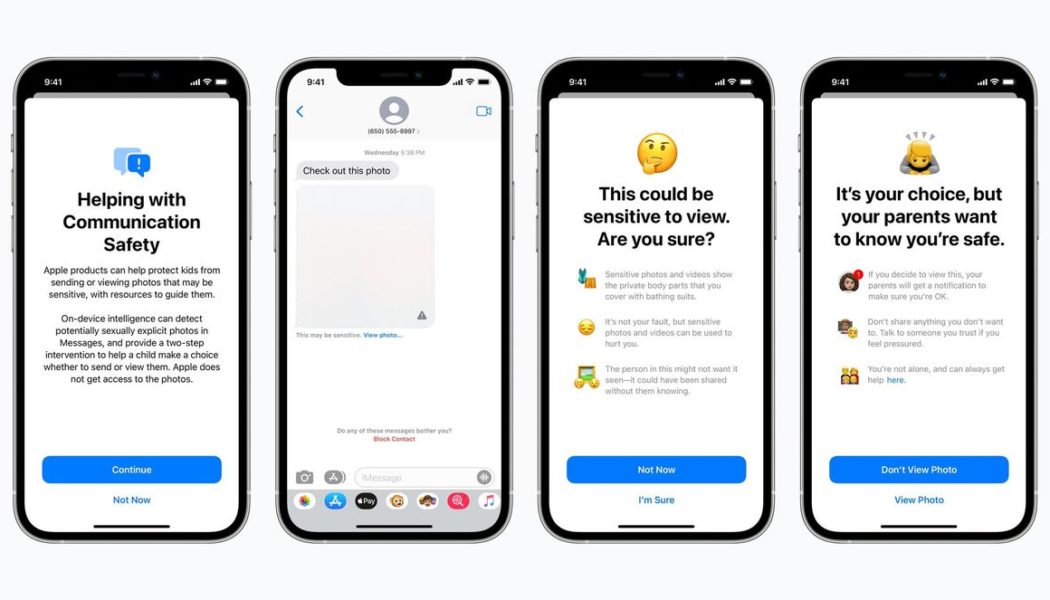

The other updates, however, have generated far more backlash. One of them adds a parental control option to Messages, obscuring sexually explicit pictures for users under 18 and sending parents an alert if a child 12 or under views or sends these pictures.

The final new feature scans iCloud Photos images to find child sexual abuse material, or CSAM, and reports it to Apple moderators — who can pass it on to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, or NCMEC. Apple says it’s designed this feature specifically to protect user privacy while finding illegal content. Critics say that same designs amounts to a security backdoor.

What is Apple doing with Messages?

Apple is introducing a Messages feature that’s meant to protect children from inappropriate images. If parents opt in, devices with users under 18 will scan incoming and outgoing pictures with an image classifier trained on pornography, looking for “sexually explicit” content. (Apple says it’s not technically limited to nudity but that a nudity filter is a fair description.) If the classifier detects this content, it obscures the picture in question and asks the user whether they really want to view or send it.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22774655/CCEA6371_9191_46CC_BDE4_B2DAB4CC4409.jpeg)

The update — coming to accounts set up as families in iCloud on iOS 15, iPadOS 15, and macOS Monterey — also includes an additional option. If a user taps through that warning and they’re under 13, Messages will be able to notify a parent that they’ve done it. Children will see a caption warning that their parents will receive the notification, and the parents won’t see the actual message. The system doesn’t report anything to Apple moderators or other parties.

The images are detected on-device, which Apple says protects privacy. And parents are notified if children actually confirm they want to see or send adult content, not if they simply receive it. At the same time, critics like Harvard Cyberlaw Clinic instructor Kendra Albert have raised concerns about the notifications — saying they could end up outing queer or transgender kids, for instance, by encouraging their parents to snoop on them.

What does Apple’s new iCloud Photos scanning system do?

The iCloud Photos scanning system is focused on finding child sexual abuse images, which are illegal to possess. If you’re a US-based iOS or iPadOS user and you sync pictures with iCloud Photos, your device will locally check these pictures against a list of known CSAM. If it detects enough matches, it will alert Apple’s moderators and reveal the details of the matches. If a moderator confirms the presence of CSAM, they’ll disable the account and report the images to legal authorities.

Is CSAM scanning a new idea?

Not at all. Facebook, Twitter, Reddit, and many other companies scan users’ files against hash libraries, often using a Microsoft-built tool called PhotoDNA. They’re also legally required to report CSAM to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), a nonprofit that works alongside law enforcement.

Apple has limited its efforts until now, though. The company has said previously that it uses image matching technology to find child exploitation. But in a call with reporters, it said it’s never scanned iCloud Photos data. (It confirmed that it already scanned iCloud Mail but didn’t offer any more detail about scanning other Apple services.)

Is Apple’s new system different from other companies’ scans?

A typical CSAM scan runs remotely and looks at files that are stored on a server. Apple’s system, by contrast, checks for matches locally on your iPhone or iPad.

The system works as follows. When iCloud Photos is enabled on a device, the device uses a tool called NeuralHash to break these pictures into hashes — basically strings of numbers that identify the unique characteristics of an image but can’t be reconstructed to reveal the image itself. Then, it compares these hashes against a stored list of hashes from NCMEC, which compiles millions of hashes corresponding to known CSAM content. (Again, as mentioned above, there are no actual pictures or videos.)

If Apple’s system finds a match, your phone generates a “safety voucher” that’s uploaded to iCloud Photos. Each safety voucher indicates that a match exists, but it doesn’t alert any moderators and it encrypts the details, so an Apple employee can’t look at it and see which photo matched. However, if your account generates a certain number of vouchers, the vouchers all get decrypted and flagged to Apple’s human moderators — who can then review the photos and see if they contain CSAM.

Apple emphasizes that it’s exclusively looking at photos you sync with iCloud, not ones that are only stored on your device. It tells reporters that disabling iCloud Photos will completely deactivate all parts of the scanning system, including the local hash generation. “If users are not using iCloud Photos, NeuralHash will not run and will not generate any vouchers,” Apple privacy head Erik Neuenschwander told TechCrunch in an interview.

Apple has used on-device processing to bolster its privacy credentials in the past. iOS can perform a lot of AI analysis without sending any of your data to cloud servers, for example, which means fewer chances for a third party to get their hands on it.

But the local / remote distinction here is hugely contentious, and following a backlash, Apple has spent the past several days drawing extremely subtle lines between the two.

Why are some people upset about these changes?

Before we get into the criticism, it’s worth saying: Apple has gotten praise for these updates from some privacy and security experts, including the prominent cryptographers and computer scientists Mihir Bellare, David Forsyth, and Dan Boneh. “This system will likely significantly increase the likelihood that people who own or traffic in [CSAM] are found,” said Forsyth in an endorsement provided by Apple. “Harmless users should experience minimal to no loss of privacy.”

But other experts and advocacy groups have come out against the changes. They say the iCloud and Messages updates have the same problem: they’re creating surveillance systems that work directly from your phone or tablet. That could provide a blueprint for breaking secure end-to-end encryption, and even if its use is limited right now, it could open the door to more troubling invasions of privacy.

An August 6th open letter outlines the complaints in more detail. Here’s its description of what’s going on:

While child exploitation is a serious problem, and while efforts to combat it are almost unquestionably well-intentioned, Apple’s proposal introduces a backdoor that threatens to undermine fundamental privacy protections for all users of Apple products.

Apple’s proposed technology works by continuously monitoring photos saved or shared on the user’s iPhone, iPad, or Mac. One system detects if a certain number of objectionable photos is detected in iCloud storage and alerts the authorities. Another notifies a child’s parents if iMessage is used to send or receive photos that a machine learning algorithm considers to contain nudity.

Because both checks are performed on the user’s device, they have the potential to bypass any end-to-end encryption that would otherwise safeguard the user’s privacy.

Apple has disputed the characterizations above, particularly the term “backdoor” and the description of monitoring photos saved on a user’s device. But as we’ll explain below, it’s asking users to put a lot of trust in Apple, while the company is facing government pressure around the world.

What’s end-to-end encryption, again?

To massively simplify, end-to-end encryption (or E2EE) makes data unreadable to anyone besides the sender and receiver; in other words, not even the company running the app can see it. Less secure systems can still be encrypted, but companies may hold keys to the data so they can scan files or grant access to law enforcement. Apple’s iMessages uses E2EE; iCloud Photos, like many cloud storage services, doesn’t.

While E2EE can be incredibly effective, it doesn’t necessarily stop people from seeing data on the phone itself. That leaves the door open for specific kinds of surveillance, including a system that Apple is now accused of adding: client-side scanning.

What is client-side scanning?

The Electronic Frontier Foundation has a detailed outline of client-side scanning. Basically, it involves analyzing files or messages in an app before they’re sent in encrypted form, often checking for objectionable content — and in the process, bypassing the protections of E2EE by targeting the device itself. In a phone call with The Verge, EFF senior staff technologist Erica Portnoy compared these systems to somebody looking over your shoulder while you’re sending a secure message on your phone.

Is Apple doing client-side scanning?

Apple vehemently denies it. In a frequently asked questions document, it says Messages is still end-to-end encrypted and absolutely no details about specific message content are being released to anybody, including parents. “Apple never gains access to communications as a result of this feature in Messages,” it promises.

It also rejects the framing that it’s scanning photos on your device for CSAM. “By design, this feature only applies to photos that the user chooses to upload to iCloud,” its FAQ says. “The system does not work for users who have iCloud Photos disabled. This feature does not work on your private iPhone photo library on the device.” The company later clarified to reporters that Apple could scan iCloud Photos images synced via third-party services as well as its own apps.

As Apple acknowledges, iCloud Photos doesn’t even have any E2EE to break, so it could easily run these scans on its servers — just like lots of other companies. Apple argues its system is actually more secure. Most users are unlikely to to have CSAM on their phone, and Apple claims only around 1 in 1 trillion accounts could be incorrectly flagged. With this local scanning system, Apple says it won’t expose any information about anybody else’s photos, which wouldn’t be true if it scanned its servers.

Are Apple’s arguments convincing?

Not to a lot of its critics. As Ben Thompson writes at Stratechery, the issue isn’t whether Apple is only sending notifications to parents or restricting its searches to specific categories of content. It’s that the company is searching through data before it leaves your phone.

Instead of adding CSAM scanning to iCloud Photos in the cloud that they own and operate, Apple is compromising the phone that you and I own and operate, without any of us having a say in the matter. Yes, you can turn off iCloud Photos to disable Apple’s scanning, but that is a policy decision; the capability to reach into a user’s phone now exists, and there is nothing an iPhone user can do to get rid of it.

CSAM is illegal and abhorrent. But as the open letter to Apple notes, many countries have pushed to compromise encryption in the name of fighting terrorism, misinformation, and other objectionable content. Now that Apple has set this precedent, it will almost certainly face calls to expand it. And if Apple later rolls out end-to-end encryption for iCloud — something it’s reportedly considered doing, albeit never implemented — it’s laid out a possible roadmap for getting around E2EE’s protections.

Apple says it will refuse any calls to abuse its systems. And it boasts a lot of safeguards: the fact that parents can’t enable alerts for older teens in Messages, that iCloud’s safety vouchers are encrypted, that it sets a threshold for alerting moderators, and that its searches are US-only and strictly limited to NCMEC’s database.

Apple’s CSAM detection capability is built solely to detect known CSAM images stored in iCloud Photos that have been identified by experts at NCMEC and other child safety groups. We have faced demands to build and deploy government-mandated changes that degrade the privacy of users before, and have steadfastly refused those demands. We will continue to refuse them in the future. Let us be clear, this technology is limited to detecting CSAM stored in iCloud and we will not accede to any government’s request to expand it.

The issue is, Apple has the power to modify these safeguards. “Half the problem is that the system is so easy to change,” says Portnoy. Apple has stuck to its guns in some clashes with governments; it famously defied a Federal Bureau of Investigation demand for data from a mass shooter’s iPhone. But it’s acceded to other requests like storing Chinese iCloud data locally, even if it insists it hasn’t compromised user security by doing so.

Stanford Internet Observatory professor Alex Stamos also questioned how well Apple had worked with the larger encryption expert community, saying that the company had declined to participate in a series of discussions about safety, privacy, and encryption. “With this announcement they just busted into the balancing debate and pushed everybody into the furthest corners with no public consultation or debate,” he tweeted.

How do the benefits of Apple’s new features stack up against the risks?

As usual, it’s complicated — and it depends partly on whether you see this change as a limited exception or an opening door.

Apple has legitimate reasons to step up its child protection efforts. In late 2019, The New York Times published reports of an “epidemic” in online child sexual abuse. It blasted American tech companies for failing to address the spread of CSAM, and in a later article, NCMEC singled out Apple for its low reporting rates compared to peers like Facebook, something the Times attributed partly to the company not scanning iCloud files.

Meanwhile, internal Apple documents have said that iMessage has a sexual predator problem. In documents revealed by the recent Epic v. Apple trial, an Apple department head listed “child predator grooming” as an under-resourced “active threat” for the platform. Grooming often includes sending children (or asking children to send) sexually explicit images, which is exactly what Apple’s new Messages feature is trying to disrupt.

At the same time, Apple itself has called privacy a “human right.” Phones are intimate devices full of sensitive information. With its Messages and iCloud changes, Apple has demonstrated two ways to search or analyze content directly on the hardware rather than after you’ve sent data to a third party, even if it’s analyzing data that you have consented to send, like iCloud photos.

Apple has acknowledged the objections to its updates. But so far, it hasn’t indicated plans to modify or abandon them. On Friday, an internal memo acknowledged “misunderstandings” but praised the changes. “What we announced today is the product of this incredible collaboration, one that delivers tools to protect children, but also maintain Apple’s deep commitment to user privacy,” it reads. “We know some people have misunderstandings, and more than a few are worried about the implications, but we will continue to explain and detail the features so people understand what we’ve built.”