Anyone who listens to Beethoven as much as Beyoncé knows it is basically impossible to find the perfect recording of your favorite violinist playing in the best concert hall with the ideal conductor.

Apple believes it has solved this problem.

The world’s richest company released a sleek new product this week that was years in the making and had to meet its exacting standards before it was ready to be used by millions of people. But it wasn’t a phone, a gadget or an AI chatbot. The latest innovation from Apple was a better way of listening to classical music.

The mere announcement of a stand-alone app for the genre was music to the ears of flummoxed artists and frustrated aficionados who were desperate for a major classical-music streaming platform that actually worked. That is the point of Apple Music Classical. It is a bespoke product for the Baroque period and beyond. It was designed to bring order to the chaos of information, the holy grail of many tech ventures, and simplify the unnecessarily complex.

And it only exists because of a curious failure by the most successful music-streaming services.

“We always had a problem,” said Jonathan Gruber, the head of Apple Music’s classical programming. “A big, big problem.”

The problem was the way that classical music is categorized. The structure of classical music is completely different from pop music’s, which makes it extremely difficult for it to function in the streaming era.

Even the most sophisticated algorithms from the most technologically advanced companies are too clumsy to handle composers like Mozart and Brahms. That’s because they were made for individual artists like Bad Bunny and Madonna. If you want to hear a Bad Bunny song, it will be in your ears within seconds. If you want to hear a Brahms piano concerto, good luck. Try sifting through hundreds of recordings without a standardized format to track down one movement from a particular soloist who has performed it several times. You could listen to an entire Madonna album in the time it takes to find the right Mozart.

It is a big, big problem. And it drives Bruce Kovner bananas.

“I’ve been working on solving this kind of problem for my own personal consumption for 20 years,” said Mr. Kovner, a retired hedge-fund manager and the chairman emeritus of the Juilliard School’s board.

In fact, it has vexed classical music for longer than two decades, as the problem goes back to “the establishment of recordings over a century ago,” said Jane Gottlieb, Juilliard’s vice president for library and information resources. But it is especially annoying that Apple Music and Spotify have turned our phones into jukeboxes and still can’t figure out Bach suites. The experience of classical music on major streaming platforms would make Yo-Yo Ma want to smash his cello.

Mr. Kovner hacked together his own system—ripping thousands of albums, tagging the recordings to make them searchable and subscribing to Spotify and niche services like Idagio and Qobuz to fill the holes in his collection—because he was so exasperated by the streaming options.

“They treat every piece as if it is the same,” said Mr. Kovner. “For classical-music nuts like me, that’s not the case. Every performance is interesting when it is unique.”

But you don’t have to be a nut to understand why classical music breaks the algorithms.

You could just compare Taylor Swift and Tchaikovsky. For a Taylor Swift pop song, the essential pieces of metadata, or the taxonomic labels that categorize information, are title, album and artist. The metadata for a Tchaikovsky track can include not just the name of the work, composer and artist, but also the nickname, movement, key, opus number, orchestra, soloist and conductor. “It gets really nerdy and very specific—and very complicated,” said Ms. Gottlieb.

Another way of thinking about classical music’s biggest problem is distinguishing repertoire from recordings. A pop star like Taylor Swift is the recording artist for her repertoire. But one piece of Tchaikovsky’s repertoire has many recordings, as if every Taylor Swift single had thousands of covers. The streaming platforms are optimized for Taylor Swift and not Tchaikovsky.

“We knew we needed to fix the product in terms of search and discovery,” said Mr. Gruber.

That required taking vast quantities of information and turning them into something digestible, then accessible, then consumable. This is one of the fundamental challenges in almost every industry today. There has never been so much available data, but it can become too much data without the proper metadata. For any business that depends on search— Netflix, Google, ChatGPT and even this very newspaper—metadata is one of the secrets to organizing the universe.

It is why this app that brings the past into the present also happens to be a peek at the future.

But the problem of classical music turned out to be so big that not even a company worth $2.5 trillion could solve it alone.

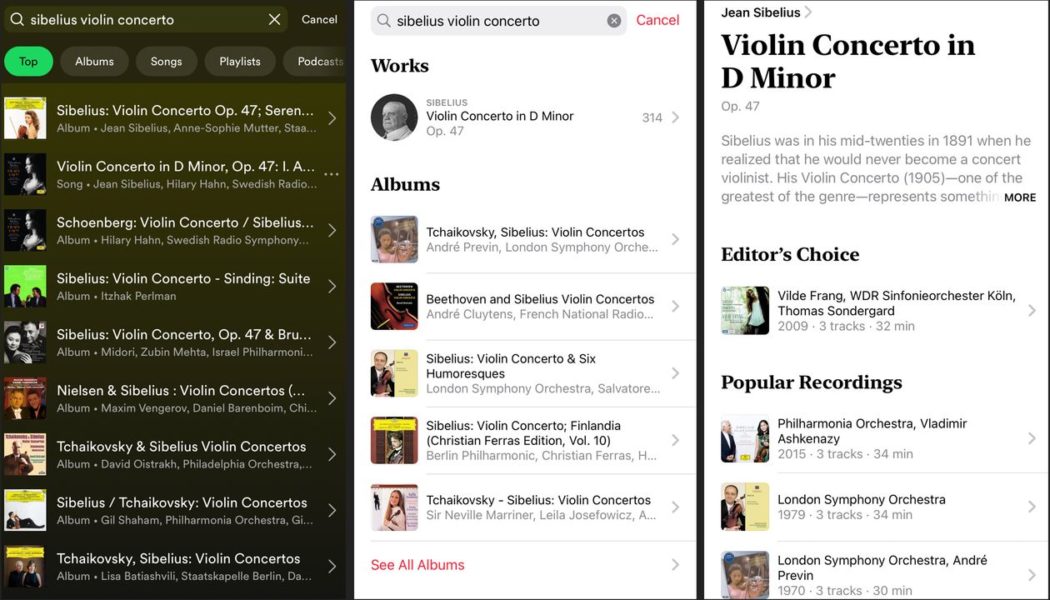

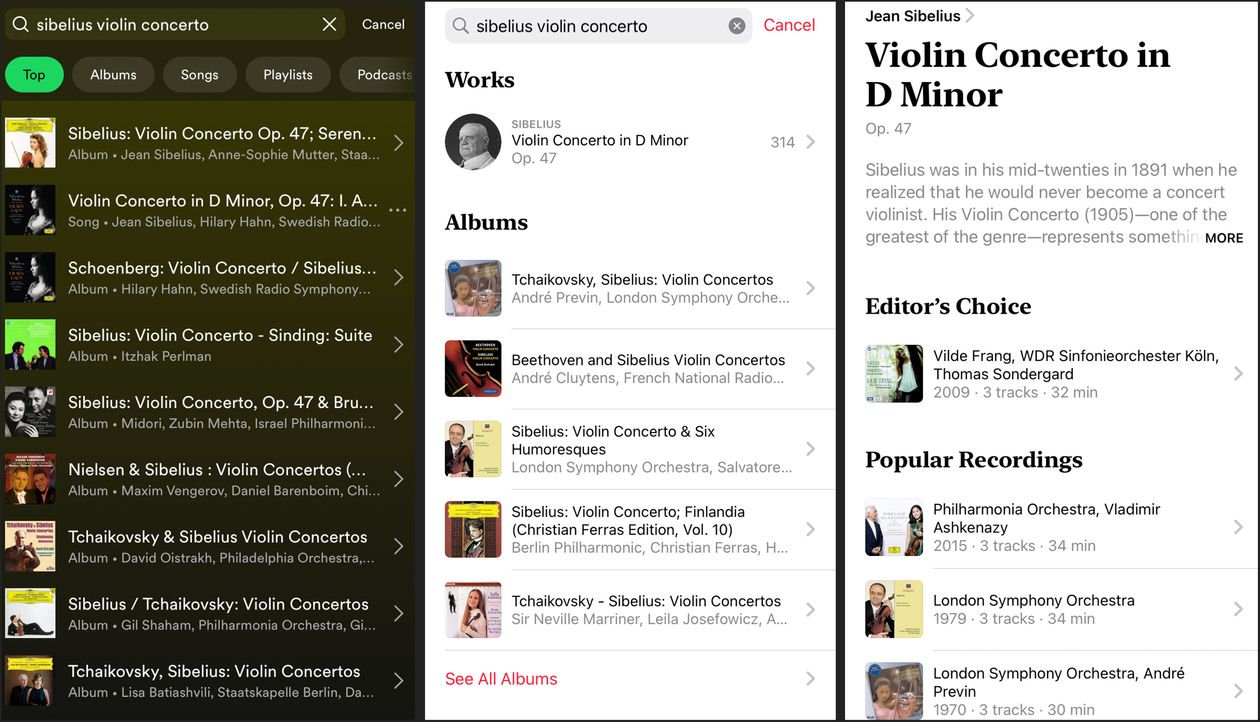

A search for the Sibelius violin concerto on Spotify (left) returns a list of recordings. On Apple Music Classical (center), subscribers can sort through hundreds of results that have been curated by editors (right).

Instead, Apple studied the market for classical-only products and orchestrated a takeover of Primephonic, a startup based in Amsterdam with a few dozen employees. As conservatory-trained musicians fluent in code, they were uniquely qualified for this line of infrastructural work.

“What we have done over the years is design and build a classical-music database that consists of every data attribute of all composed and recorded work,” said Primephonic co-founder Veronica Neo, who now leads Apple Music Classical’s data operations.

This better data created by the Dutch company’s opera singers and clarinetists was the key to dragging classical music into the 21st century. To be more specific, it was the better metadata.

Any tech product that looks and feels just right is probably because of something hiding underneath that you cannot see. In music, that invisible metadata is the information embedded in each track, the atomized bits that let people type a few letters and find what they are looking for. The only way to solve the big, big problem was to focus on the smallest details.

Apple acquired Primephonic for an undisclosed price in 2021 and inherited that precious metadata. Now it is the engine behind Apple Music Classical, which comes included with an Apple Music subscription.

A flaw of one product became the defining feature of another.

Apple Music Classical offers access to more than 20,000 composers, 115,000 works and five million tracks. If you search for Sibelius’s famous violin concerto, one tap brings you to a page with 314 options, including the five most popular recordings and one that Apple’s editors selected as their favorite, plus related pieces of repertoire chosen by classical specialists. It is the kind of smart human curation that shows how people can have a role in a world being conquered by generative artificial intelligence. Some of those recordings can be heard in high-resolution lossless and spatial audio, which is meant to re-create the sound quality of sitting in Carnegie Hall.

Not every problem is solved just yet. When I tried sorting the Sibelius offerings by artist name, some were listed by orchestra and others by violinist, which was confusing. But it was surprisingly easy to search those 314 recordings by soloist, ensemble and even conductor. The interface could also be more intuitive. After fiddling with the app for a few hours, Mr. Kovner provided a note of skepticism. “I will keep using it for a while to get a better feel for what it can do,” he said in an email.

Mr. Gruber says he’s confident that Apple Music Classical will improve with time: “The search for perfection in classical music is the longest piece of string imaginable. This is just the beginning.”

In the meantime, Apple is still looking up at Spotify, the giant of the streaming business. But it might have to squint to see another rival.

Idagio is a classical-music service that was founded in 2015 by Till Janczukowicz, who set out to solve the problem of metadata in a similar way and found a receptive audience. On the morning Apple Music Classical went live, I asked him about competing against the most valuable company on the planet. He didn’t seem too intimidated. He sounded like someone who had been listening to a nocturne all day.

“I think it is great that one of the key players is paying attention to this,” he said. “Finally.”

Write to Ben Cohen at ben.cohen@wsj.com