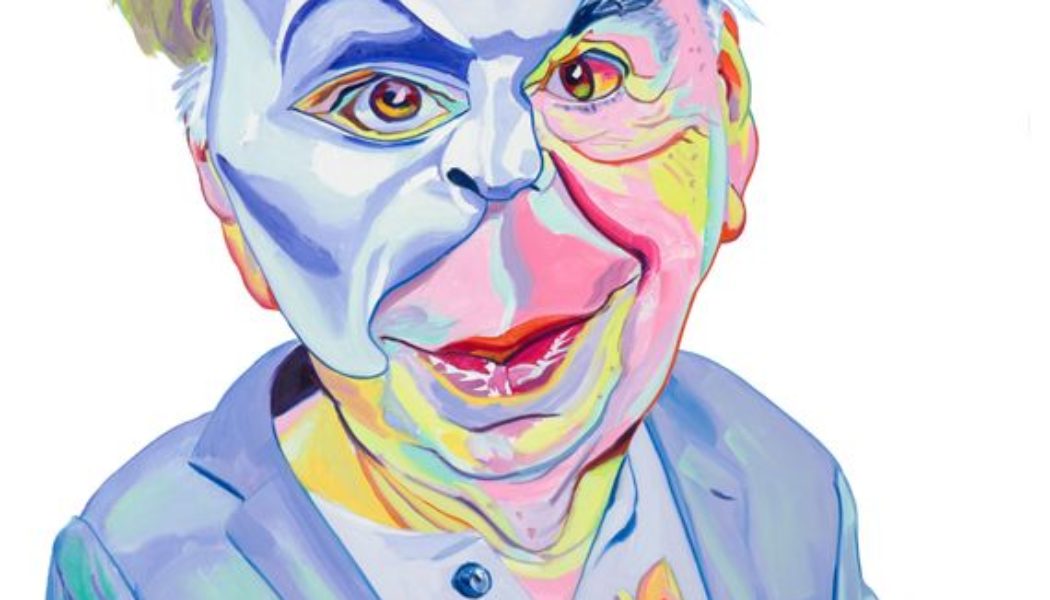

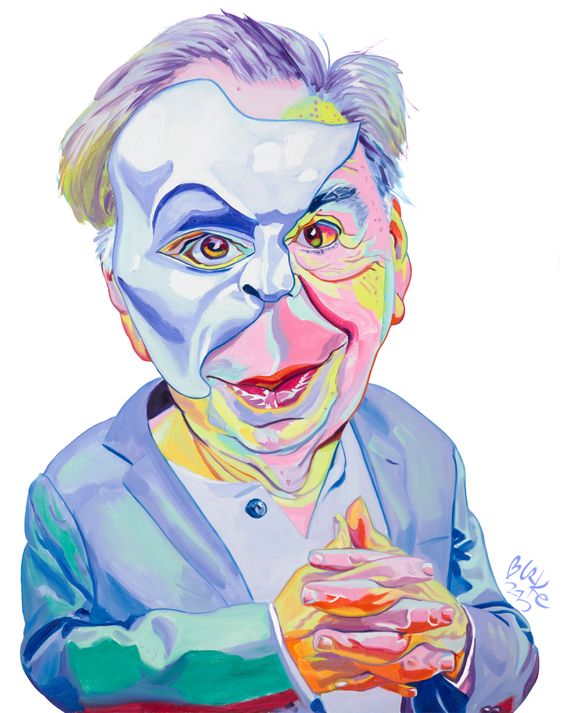

Illustration: Philip Burke

In 1988, New York magazine ran a cover story about the arrival of a new Broadway show. Described as an “old-fashioned, romantic musical that assaults the senses,” The Phantom of the Opera told the tale of a deformed composer — the masked Phantom — who falls tragically in love with a beautiful soprano. The actual composer, Andrew Lloyd Webber, had written it for his mistress turned wife, Sarah Brightman; their affair had been all over the tabloids back in London. Interviewed at the couple’s $5.5 million duplex in Trump Tower, Lloyd Webber called the show his “favorite” to date, all due respect to Evita, and, in any case, it was hard to argue with a record-breaking $17 million in advance tickets. Phantom might have been a British musical based on a French novel, but the show’s fin de siècle grandeur fit perfectly with the decadence of the Reagan years: opulent architecture, sexual nostalgia, rock-and-roll pyrotechnics. (Plans to release a flock of live pigeons had been scrapped before the London premiere.) Even the unforgiving Frank Rich, in an otherwise negative review for the New York Times, admitted, “It may be possible to have a terrible time at The Phantom of the Opera, but you’ll have to work at it.”

Now Phantom is finally closing. In its 35-year run, the longest in Broadway history, Phantom has grossed over $1.3 billion and exceeded 20 million viewers; two weeks ago, it brought in a record-setting $3 million from ticket holders eager to pay their respects. The official cause is the pandemic, but the fact is that having a terrible time at Phantom today takes no effort at all. The production is simply miserable, succumbing in its old age to anemic tempos and wretched acting; there is a shocking amount of dead air for a show in which the performers never stop singing. Emilie Kouatchou, marketed a little too proudly as the first Black actress to play Christine on Broadway, is a capable soprano doomed to a thankless role that often involves begging men to “guide” her. It is hard to ignore that Phantom has always been a classic rape fantasy; its appeal hinges entirely on the charisma of its titular bodice ripper, a self-described ugly virgin who plots violent attacks on the public from his basement. Fans have long speculated that the extravagant title song, in which the Phantom ferries Christine across a fog-covered subterranean lake, relies on body doubles and prerecorded vocals. Only the famous chandelier still thrills: Its ominous ascent during the organ overture (also likely pretaped) remains a true coup de théâtre. It hangs menacingly over the orchestra section, a Chekhov’s light fixture; but at the act break, it will “fall” lightly back onto the stage like Peter visiting the Darlings. (To ensure brand continuity, Lloyd Webber’s first new Broadway show in almost a decade, Bad Cinderella, has opened around the block to poor reviews. Lloyd Webber himself missed the premiere to be with his son, who died over the weekend of gastric cancer.)

Why did anyone ever like this? To dismiss Phantom as just another spectacle for a spectacular age (one could just as easily praise it for this, and many did) would be to contradict the Phantom himself. Lloyd Webber’s previous work, such as the gaudy colossus Cats, had earned him the reputation of an opportunist with few principles beyond the British pound. By comparison, Phantom was an almost intellectual work, an artist’s statement from a man whom few had ever accused of artistry. The Phantom was no entertainer, preferring to compose in literal obscurity beneath the opera house rather than betray his belief in music as the highest expression of the human spirit; he stood for devotion, not diversion.

Through Phantom, Lloyd Webber presented an argument for the destiny of musical theater itself. The operatic tradition had always been divided over the relationship between music and drama, and this debate had reemerged in Lloyd Webber’s day. His contemporary Stephen Sondheim was a studied modernist who brought dramatic heft to musical theater in the 1970s. By contrast, Lloyd Webber had no ear for drama; his characters simply declaimed their emotions directly into the audience, as if by T-shirt cannon. What he offered was something different: an experience of sheer musical transcendence. This emphasis on the musical part of musical theater served as both a defense of his earlier endeavors, which by this reasoning could be considered serious works of art, and a vision for the future of Broadway. Night after night, the Phantom promised the audience that, for two and a half hours, nothing — neither plot nor character, not social issues, not even good taste — would be more important than what happened when that invisible beam of music shot across the darkened theater into their souls.

Lloyd Webber was born in postwar London to a family of music lovers. His father, an accomplished organist and little-known composer, taught composition at the Royal College of Music in London, while his mother was a successful piano teacher frustrated with her husband’s professional complacency. As a teenager, Lloyd Webber wept with emotion upon hearing a radio broadcast of Tosca, the 1900 opera by Puccini. “This was truly theatre music that I never dreamed possible,” he writes in his 2018 memoir, Unmasked. The young man was under considerable pressure to distinguish himself musically. His mother became so morbidly obsessed with a piano prodigy that she effectively adopted him into the family; meanwhile, her actual son planned a halfhearted suicide attempt. Lloyd Webber still vividly remembers the time his father played him a recording of “Some Enchanted Evening,” a love song from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific. “Andrew,” his father told him, “if you ever write a tune half as good as this, I shall be very, very proud of you.”

Let no one say he didn’t try. Lloyd Webber’s first produced musical, Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat, sounded like a Sunday-school pantomime written by a teenager, because it was. But by his father’s death in 1982, Lloyd Webber had several smash hits under his belt: Jesus Christ Superstar, a rock opera; Evita, a sympathetic look at fascism in Argentina; and, of course, Cats. He had practically defined the British megamusical of the 1980s: breathtaking visuals, timeless themes, and above all a fully sung-through structure, usually with a strong pop influence. His work divided critics, but Lloyd Webber himself, a merry populist with a growing Pre-Raphaelite art collection, saw no contradiction between artistic integrity and commercial appeal. Early on, he had learned to promote his music by releasing concept albums and lead singles — “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” from Evita reached No. 1 on the U.K. singles charts in 1977 — and his shows were so profitable that Margaret Thatcher, when challenged on her government’s cuts to public funding for the theater, replied, “Look at Andrew Lloyd Webber!” Indeed, given the huge moving sets and live sound mixing — a practice Lloyd Webber pioneered for the theater — it was hard to look away. His next hit, Starlight Express, was a synth-pop nightmare about racing trains that featured androidlike actors who zoomed around the audience on roller skates. That production’s director, Trevor Nunn, who had also worked on Cats, told the press it was like going to Disneyland: “Here is my money. Hit me with the experience.”

Still, Lloyd Webber longed to be thought of as a serious composer. He was proud that Cats was built around a fugue, and, like Rachmaninoff before him, he wrote variations on Paganini’s Caprice No. 24. He had become obsessed with the “mesmeric possibilities” of the unusual 7/8 time signature after hearing it in one of Prokofiev’s piano sonatas as a youth, and he would make a self-impressed point of putting a juddering 7/8 section into every score. Yet there was something labored and prosaic about Lloyd Webber’s music. His father is said to have asked his composition pupils, “Why write six pages when six bars will do?” But the younger Lloyd Webber, a self-described “maximalist,” preferred to elongate his melodic lines far beyond their natural conclusions, and he was slavishly devoted to the downbeat.

This schoolboy approach did make Lloyd Webber a passable writer of pastiche: rock and pop mostly, without a hint of jazz, and the classical music his father had schooled him in. The tune for “Memory” from Cats was originally ersatz Puccini, intended for a show about a cut song from the opera La Bohème. The elder Lloyd Webber, an “acknowledged expert on Puccini,” loved it — though the song also recalled Ravel’s Boléro, slowed down and played in a maudlin 12/8 time. Critics noticed this sort of thing a lot. The favorite ballad from Superstar, “I Don’t Know How to Love Him,” appeared to take its plaintive melody from the second movement of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, and underneath “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina,” one could hear the Paraguayan harp plucking something like Bach’s Prelude in C major. The most puzzling thing about these borrowings was their apparent insouciance: The composer simply did not seem to care. Lloyd Webber’s longtime orchestrator would defend him on the grounds that there simply “aren’t that many notes.” But as the drama critic John Simon put it for New York, “It’s not so much that Lloyd Webber lacks an ear for melody as that he has too much of one for other people’s melodies.”

In truth, Lloyd Webber was borrowing more than music. At 21, he had fallen in love with a “deliciously open-faced” 16-year-old girl named Sarah Hugill, marrying her just weeks after her 18th birthday; now he was leaving her for Brightman, a former Cats actress 12 years his junior whom the tabloids dubbed “Sarah II.” Guilty over the divorce and eager to challenge himself artistically, Lloyd Webber landed on the idea of Requiem, a Requiem Mass dedicated to his late father — with a soloist part that would show off Brightman’s three-octave lyric soprano, which was clearly in demand. On a hot summer’s night in 1984, Lloyd Webber went with his new wife to see a fledgling musical by the director Ken Hill, who wanted Brightman for his female lead. The production, which concerned a pretty soprano and the tortured composer who is in love with her, featured classic opera arias with new lyrics by Hill. Brightman, then eyeing actual opera, was unconvinced, but Lloyd Webber thought the show had potential as a “Rocky Horror Picture–type musical” and agreed to produce it and compose an original title song. It was called The Phantom of the Opera.

In his memoir, Lloyd Webber is at pains to minimize the role played by Hill’s Phantom in the genesis of his own, though he briskly acknowledges that the demo he recorded for Hill was an early version of the song “The Phantom of the Opera,” down to the iconic organ chords. His preferred origin story is that, during rehearsals for Requiem, he happened to pick up a 50-cent copy of Gaston Leroux’s original 1910 novel Le Fantôme de l’Opéra on Fifth Avenue, suddenly realizing that it could furnish the “high romance” he wanted to write for Brightman. The novel, set at the Opéra Garnier in 1880s Paris, is about an ingénue named Christine Daaé who believes she is being tutored by an unseen angel sent by her dead father; in fact, her teacher is the rumored Opera Ghost, a disfigured but very human composer named Erik who has fallen dangerously in love with her. The story had already been adapted many times, including as a classic 1925 silent film starring Lon Chaney; later films depicted the Phantom as (ironically) an enraged victim of musical plagiarism. But Lloyd Webber saw something else: a man in love with a voice. His Phantom would be an inverted Orpheus, beckoning his beloved to the underworld with music; here was an opportunity for passion, for real gravity. Indeed, for the first time in his career, it seemed to Lloyd Webber that he might have something to say.

The Phantom of the Opera opened on the West End in 1986. To an extent, it did what Cole Porter’s Kiss Me, Kate had done for Shakespeare: It provided a night at the opera for people who, as a rule, did not go to the opera. In the English-speaking world, opera is kept alive by an elite donor class whose tastes rarely venture beyond the 19th century. (The composer Pierre Boulez once remarked that the best way to modernize opera would be to “blow the opera houses up.”) What Lloyd Webber offered, alternatively, was a pleasing impression of opera — continuous singing, throbbing vibrato, very high notes — without the infamous longueurs or unintelligible vowels. Critics agreed that the score was his most mature, incorporating modest experiments alongside the opera pastiche; here and there, one caught a glimpse of genuine musical intelligence. But the true star of Phantom was music itself; there was simply so much of it. It was the first show for which Lloyd Webber shared a book credit, and his characters discussed music incessantly: who should sing it, how to market it, what gave it value. In essence, Lloyd Webber had written a reply to critics who saw him (positively or not) as a purveyor of theatrical delights, countering that the experience of listening to music was a matter of grave artistic importance.

Opera had a significant conceptual role to play in Phantom. Act One began with a lumbering rehearsal for Hannibal, a fictional caricature of 19th-century grand opéra complete with dancing slave girls and a large fake elephant. Lloyd Webber’s stated target of parody was the hugely successful Giacomo Meyerbeer, remembered today for his elaborate stage effects. The direct parallels between the two men — Meyerbeer’s Le Prophète had even featured roller skates back in 1849 — might not have escaped Lloyd Webber himself. This, Phantom assured its audience, was opera at its most tedious, and it was perfectly natural to dislike it. A great deal of the plot was devoted to the Phantom’s attempts to replace Carlotta, a fussy coloratura soprano with a thick Italian accent, with his beloved Christine. “We smile because she represents the old way with opera, but she is not a figure of fun,” Lloyd Webber writes of Carlotta, whose interpretation of a Hannibal aria is turgid and self-indulgent. By contrast, Christine’s rendition has a clearer, poppier quality, helped along by the fact that the melody bears more resemblance to a Linda Ronstadt ballad than a Meyerbeer aria. For the Phantom, only Christine’s voice offers a way out of opera and into “a new sound” — even if that sound happens to be 1980s pop.

There was a touch of history in this. In late-19th-century Paris, the true phantom was grand opéra itself, treading the boards even as successors emerged both at home and across the Atlantic. French and English operettas were becoming wildly popular in America — a parody of opera for a nation with little native operatic tradition — and by the early 20th century, comic opera had come together with minstrelsy and vaudeville to form the basis of what today we call musical theater. At first, the musical comedy resembled a plotless revue — until the arrival of Show Boat in 1927, a melodrama about miscegenation with lofty aspirations. “Is there a form of musical play tucked away somewhere in the realm of possibilities which could attain the heights of grand opera and still keep sufficiently human to be entertaining?” wondered its playwright and lyricist, Oscar Hammerstein II. In his later “book musicals” with composer Richard Rodgers, resurrecting opera came to mean something very specific: smoothly integrating the music into the play to produce a single dramatic whole. “Some Enchanted Evening” might have sounded like a sweeping love song when played in one’s sitting room, but in the context of South Pacific, it was a widower’s tongue-tied expression of affection for a woman he barely knew.

For Lloyd Webber, the benefit of drama was to give definite shape to the abstract emotionality of music: A melody might sound sad, but only a lament could be tragic. But for this very reason, the music in Phantom rarely served a dramatic end — rather, it strutted around the stage like it owned the place. As lyricist Charles Hart reported, director Hal Prince was so focused on making Phantom into a crowd-pleaser that “any actor looking for motivation had to look elsewhere as far as Prince was concerned.” Lloyd Webber evidently felt the same about Hart’s lyrics, recalling with amusement how the beleaguered lyricist ended up tossing the word somehow into “Wishing You Were Somehow Here Again” to sop up the extra notes. But Lloyd Webber preferred for the music to talk over the words, as when the Phantom showed up at the masquerade ball; the revelers, having just got done singing about how good masks are at hiding faces, nevertheless recognize him instantly thanks to the massive organ chords that introduce him — which, diegetically speaking, they cannot hear.

The debate over these competing priorities — music and drama — was as old as opera itself. “In an opera, the poetry simply has to be the obedient daughter of the music,” Mozart wrote in 1781, arguing that Italian opera had overcome its “miserable librettos” by ensuring that “music reigns supreme and everything else is forgotten.” Other composers, like the imperious Richard Wagner, saw music as a powerful organ of expression with no inherent content — that is, music was very good at saying things but had nothing to say. In his 1851 polemic Opera and Drama, Wagner contended that the worst opera composers used music to produce “effects without causes,” forgoing dramatic action to send impressions of feeling straight into the listener’s ears. In the American musical-theater tradition, this tension would be borne out by Rodgers’s own career as a composer. In his earlier partnership with the lyricist Lorenz Hart, Rodgers had written the melodies first, crafting sparkling tunes for forgettable plays, whereas with Hammerstein, the words came first, requiring a more mature Rodgers to compose music with a clear dramatic purpose in mind. (The former duo produced classic songs; only the latter produced classic musicals.)

In one telling, Hammerstein’s vision won out. For the 1957 musical West Side Story, the classically trained Leonard Bernstein wrote a complex, often operatic score around a recurring musical interval — the tritone, as immortalized in the melody for “Maria.” But when it came time to write a “mad aria” for Maria to sing over her lover’s dead body, Bernstein recalled that he “never got past six bars,” realizing that the tragic climax called for precisely no music at all. To be clear, drama didn’t have to be Shakespearean in order to have structural priority: Meredith Willson’s The Music Man, also from 1957, was a fully integrated musical with a corn-fed plot. Nor did a show have to be full of action in order to be dramatic, as with the thematically linked vignettes of Sondheim’s Company. The point is simply that, in all these cases, music served at drama’s pleasure. Sondheim, himself a protégé of Hammerstein, took this to extremes in the ’70s, veering away from the traditional song form in favor of accretive harmonic shapes that provided rich subtext for his lyrics — so much so that critics began complaining of having nothing to hum. The prickly composer seemed to mock this criticism in his 1979 masterpiece, Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, in which a flamboyant Italian barber is so distracted by his own melodiousness that he loses a shaving contest to Sweeney, who remains perfectly silent.

At the same time, musical theater had always grappled with a kind of royalist impulse, one that aspired to set music atop its rightful throne. By the ’80s, it was as if Lloyd Webber, ever the Tory, had sent the megamusical to America to reclaim the colonies for the crown, armed with terroristically hummable tunes. Wagner had long ago despaired of the effects of the “naked, ear-delighting, absolute-melodic melody” on the opera-going public — what we would call an earworm. (Sure enough, as soon as South Pacific opened in 1949, Frank Sinatra and Perry Como had both released covers of “Some Enchanted Evening.”) Bernstein agreed: “An F sharp doesn’t have to be considered in the mind; it is a direct hit.” Even Sondheim, who admitted to being “not a huge fan of the human voice,” wrote a pretty aria for his silly barber. Later in the original Sweeney Todd score, the triumphant orchestral blast that ended Sweeney’s murderous “Epiphany” was abruptly undercut by a soft, sickly chord, thus tingeing his elation with moral uncertainty. But for the national tour, the sickly chord would be omitted — not for dramatic reasons but presumably because this allowed the singer, who had just pulled off a musical tour de force, to be rewarded with applause.

This is what The Phantom of the Opera stood for: not opera itself, for which it had limited patience, but rather what it imagined to be operatic values, in particular the elevation of melody over everything else. If Hammerstein had wanted to dig up opera’s bones, Lloyd Webber, whose hero had always been Rodgers anyway, wanted to raise its spirit. But he was so focused on musical effects that he seemed to cut corners when it came to the actual music. For all the banging on about it, the Phantom never even bothered to clarify what his “music of the night” actually was. He cannot have meant his pallid avant-garde opera, which better resembled a children’s piano exercise than a work of French modernism. “If the Phantom is supposed to be such a brilliant musician,” a woman once asked Lloyd Webber, “why does he write such horrible music?” As for “The Music of the Night” itself, no single Lloyd Webber melody has been more accused of plagiarism: Its opening notes recall both Tosca and Lerner and Loewe’s Brigadoon, followed by a long, indisputable borrowing from Puccini’s La Fanciulla del West. This means that, even as he demanded that Christine submit to his music, the Phantom was singing someone else’s.

But if the Puccini operas he admired had placed music over drama, it was Lloyd Webber’s innovation to install music loving over music itself. The Phantom was not a musical genius but an aficionado. “Close your eyes and surrender to your darkest dreams!” he urged the audience, pontificating on the virtues of music appreciation. That’s what the music of the night really meant: music as heard in the dark, such that its sole quality became its effect on the listener. This conveniently obviated the need for music that was actually good, as far as the critics were concerned. After all, the Phantom himself was hideous; what mattered was that his music had irresistible emotional power over a practically orgasmic Christine. “You cannot win her love by making her your prisoner!” Christine’s aristocratic lover cried out to the Phantom. Yet this had always been Lloyd Webber’s strategy as a composer: not to persuade but to overwhelm. In this way, Lloyd Webber was musical theater’s irrepressible id, emerging from the orchestra pit to insist that at the form’s core lay pure musical enthusiasm.

He wasn’t entirely wrong. For centuries, people had come to the theater out of a desire to be overpowered by music; even American plots to dethrone the mega-musical could not change this. The grungy social realism of Jonathan Larson’s 1996 rock opera, Rent, was largely a feint; if anything, Rent was good evidence that theater music may be even less suited to political statements than to drama. The show wore its Puccini influences on its tattoo sleeve, and its AIDS-era anti-Establishment message sounded as generic as that of the alt-rock genre from which it borrowed; at a certain point, one wished the crazy kids would stop trying to say something and just sing. A more artful approach would arrive in Jason Robert Brown’s 1998 score for Parade, in which an unjust guilty verdict is read over a jaunty cakewalk and a Confederate march, played simultaneously and at different tempos. Even then, as my colleague Jackson McHenry noted of the recent revival, one left the theater humming the “wrong” tune: a pretty hymn to the antebellum South. A few years later, ABBA’s Mamma Mia! arrived on Broadway, unleashing the ongoing torrent of jukebox musicals that have forgone the hard labor of plagiarism in favor of stringing together the exact songs into which people actually do break out in real life.

The past decade has seen an even stranger heir to Phantom: the message musical. Atop the form, like a mad king, sits Lin-Manuel Miranda’s 2015 hip-hop opera, Hamilton; its much-discussed decision to cast actors of color as the Founding Fathers concealed the fact that its cantatalike structure and R&B pastiche brought it closer to Cats than to Company. (Lloyd Webber, horribly, credits the first rap in musical theater to Starlight Express, which is practically a work of minstrelsy.) But at least Cats was about cats; the message musical has taken Lloyd Webber’s philosophy and affixed it, with the dramatic equivalent of spirit gum, to its earnest social causes. The British musical Six, a girl-power pop concert presented by the wives of Henry VIII, should be a simple excuse to hear decent impressions of Beyoncé and Adele; its needless gesture at feminist historiography is so limp that the characters openly admit it. At the logical end of this trend lies the current jukebox musical & Juliet, an excruciating retelling of Romeo and Juliet in which a trans-feminine character is made to tearfully croak Britney Spears’s “I’m Not a Girl, Not Yet a Woman.” It is enough to make one long for the music of the night; at least the Phantom’s message was that music shouldn’t have one.

Today, it is clear that Phantom succeeded in remaking the musical in its own image. Not only did Lloyd Webber set Broadway on its current path of chintzy commercial nihilism, but he also reminded us, through his peculiar naïveté, that the greatest obstacle to musical theater as a dramatic art is music itself. Perhaps this is why we love it. Yet Lloyd Webber himself has rarely brought a hit to Broadway since. (His 500-page memoir peters out in 1986, sparing him the embarrassment of flops like the execrable Love Never Dies, a sequel to Phantom.) Curiously, his new Broadway show, Bad Cinderella, is a message musical; the classic story has been carved, like a step-sister’s heel, into a deeply misogynistic satire of beauty standards. The title song contains an almost note-for-note quotation from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “In My Own Little Corner” — from their own Cinderella. It is as if, having finally accepted that he will never write a tune half as good as Rodgers, Lloyd Webber has settled for writing a tune half-composed by him. But what’s really notable about Bad Cinderella is its lack of ambition: It is an old-fashioned book musical with plenty of dialogue and a forgettable score. It is not a train wreck, just a train. There is something pitiful about this. It’s odd to be lectured on beauty by a man who has spent his entire career blindly devoted to it. The Phantom, at least, had the courage of his convictions; he was an enlightened philistine, willing to murder in the name of beautiful music while lacking a single opinion about what made a piece of music beautiful. In the twilight of his career, Lloyd Webber has sent the ghost back to his underground lagoon, and the theater feels small and empty now. It could use a little opera.