André 3000 was never a solitary genius. Not when he put on the pith helmet and shoulder pads. Not when he kicked off a song called “Int’l Players Anthem” with an ode to fidelity and true love. Not even when he put a dozen versions of himself on stage in the video for “Hey Ya!,” an all-time classic song that will be played at weddings until the heat death of the universe, and on which he played nearly every instrument. Even when he sounded like he was rapping from outer space, his Southern accent dragged him back down to Earth, back to his roots, back to Atlanta, and more specifically, back to his friends and family. “It gives you an opportunity and support system to be as free as you can be,” he recently told NPR, reflecting on where he came from and where he finds himself now, in 2023, a starman in a brand-new galaxy, one dot in a different kind of constellation.

So New Blue Sun isn’t really a solo record. It’s also not a bandleader record in the jazz sense, like Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue or John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, where the name on the sleeve indicates the leader in the studio. It’s not the work of one person surrounded by exceptional musicians to help execute his vision; in that sense, New Blue Sun is even less of a solo record than The Love Below, André’s half of OutKast’s 2003 double album. On the first full-length release to bear his name and his name only, André 3000—a man who once christened himself Possum Aloysius Jenkins, Dookie Blossom Gain III, Funk Crusader, and Love Pusher, all at once—is oftentimes barely visible. He is a stick of nag champa perfuming the room of this record. He is a happy contributor to its world, one among many. The man who brought Afrofuturism to TRL has a new trick up his sleeve: He’s blending in.

Like every OutKast record, New Blue Sun is the product of a community. Over the past decade or so, the worlds of ambient music, electronic music, jazz, beat music, free improv, and new age in Los Angeles have congealed to create a new and far-reaching style. It encompasses everything from the DIY dub jazz of Sam Wilkes and Sam Gendel to the harpscapes of Mary Lattimore to the fluid Ethio-funk of Dexter Story. Though there’s no real center to the scene, nearly everyone either has or is about to work with Carlos Niño—percussionist, producer, founding DJ of the influential internet radio station Dublab, and connective tissue in a city designed to discourage connection. You’d call him an instigator if his presence weren’t so gentle. The music he releases under the name Carlos Niño & Friends is technically complex and spiritually sincere. He invites a few people over, they improvise freely on whatever instruments are at hand, and Niño then chops, cuts, and shapes the jams into albums that swell with unspoken but easily understood feelings—André played flute on his album from earlier this year.

André and Carlos met at Erewhon, the grocery store whose, let’s say, exclusive prices and exceptional kombucha selection have made it the go-to shop for celebs and a highly memeable avatar of L.A. wellness culture. Niño invited André to an Alice Coltrane tribute concert he was hosting that evening, and they started jamming together soon after. Though he’d puffed a tenor sax on The Love Below’s “She Lives in My Lap,” André was turned on to the true power of woodwinds when he heard champion surfer Kassia Meador play her flute at a breathwork class in Venice. This is all intensely L.A., nearly to the point of parody—we haven’t gotten to the song inspired by an ayahuasca therapy session—but it’s also the everyday reality for plenty of people who live here. When Leaving Records’ Matthewdavid, who plays “mycelium electronics” on New Blue Sun, talks about how private-press new age music has opened him to more beautiful possibilities in his life, he means it.

That heritage means that New Blue Sun might be baffling and disappointing to anyone who didn’t have an opinion on Online Ceramics’ Alice Coltrane collection. There are, as the warning label on the vinyl sleeve promises, no bars—not a single word is spoken, sung, or rapped—but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have something to say. In spite—or maybe because—of its lack of language, New Blue Sun is the most emotionally direct music André has ever made. The methods might be oblique, the instrumentation often unclear, the man himself occasionally missing in action or off on his own pursuits, but the sense of intermixed sadness, loss, and peace that permeates this music is impossible to miss.

Together with a core ensemble of guitarist Nate Mercereau and keyboardist Surya Botofasina (both responsible for some incredible music on their own), André and Niño flood this record with a mood as blue and deep as the water off Catalina. You can hear it there in the opening moments of “I swear, I Really Wanted To Make A ‘Rap’ Album But This Is Literally The Way The Wind Blew Me This Time.” It’s in the clear-eyed regret that comes through Botofasina’s keys and sticks around as the group begins to build upon it; it’s the foundation of all eight of these songs.

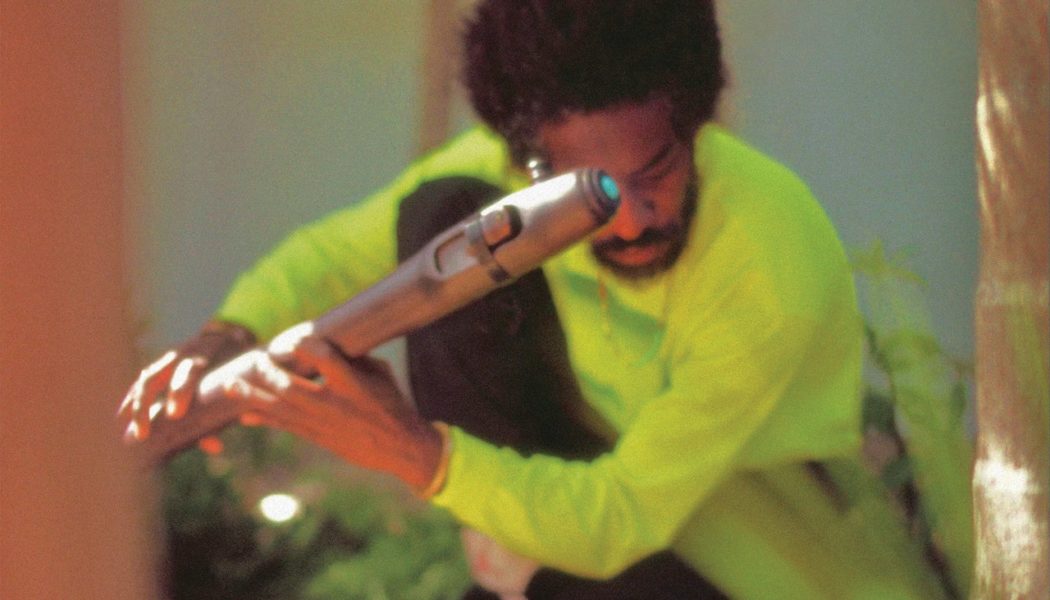

André has been playing handmade flutes for years, a devotion that has put his desire for anonymity in jeopardy. Like John Coltrane, who would invite over a friend and then spend the entire visit working out new ideas on his sax, André’s devotion to his instrument is nearly compulsive; maybe you saw him practicing at LAX. So it’s surprising that he recorded much of New Blue Sun with a digital wind instrument he’d never played before. Like a Fairlight synth set to “strings,” it makes a virtue of how little it sounds like the instrument it claims to sound like, producing a flat and buzzing tone that André learns how to manipulate over the course of the record.

The great Pharoah Sanders, whose influence is felt in the general tone of New Blue Sun more than in its actual playing, sits out the first five minutes of his classic Tauhid, allowing his band to develop the mood before he makes his entrance, piccolo in hand. André does the same on New Blue Sun, sitting back and allowing us to stare into “I swear”’s breezy darkness for three minutes before he picks up his instrument. The song yips and howls, Niño rattles his signature shells, Botofasina weaves a meshy wave of synths that swell without breaking. There’s a lot to hear and very little movement; imagine a spotlit meteorite on display in a gallery, rotating slowly so you have time to take in all its facets. Now imagine what that would make you think about.

When André does finally play, he picks his notes carefully, like he’s testing to see where he fits. The melody he dots out in “I swear” recalls Philip Glass in the nakedness of its notes, or even the writer Raymond Carver: He’s making simple gestures feel grand by virtue of their accumulation. Throughout New Blue Sun, this tends to be how he plays his instrument, whether he’s setting the theme or exploring its variations. The notation is minimal, and he repeats short and uncomfortable phrases until they begin to sound right: Listen as he dips, brushes, and dabs in “The Slang Word P(*)ssy Rolls Off The Tongue With Far Better Ease Than The Proper Word Vagina . Do You Agree?,” finally tracing a few fine, confident lines at the top of the canvas that pull the song into a new mode.

About those titles: Yes, they are long. They are playful. He misspells Gandhi’s name, yes. There is something to be said about how André can’t help but use language to both say and obfuscate what he’s feeling. It’s tempting to map some kind of narrative onto instrumental music, particularly something as gauzy and obviously personal as this. You can read the beatific sigh of New Blue Sun as a comment on the relief of anonymity André must feel, or how the safety of a group of like-minded people allows you to take a closer look at the darkness outside. If you don’t look at the tracklist, you can do that. But those song titles deflect your gaze, keep you from taking this stuff too seriously, from reading too much into it. Call it a feint, but it feels like a way of keeping the music light and exciting, of protecting the exploratory spirit that went into its creation.

Despite his lyrical virtuosity, André has always sought out what a song needs; consider the way the back half of “B.O.B” is given over to gospel rave, or how “SpottieOttieDopaliscious”’ ineffable hook is a wordless trumpet line. Here, he’s doing the same thing, moving carefully and only asserting himself when it feels right. He tests “The Slang Word” out for vulnerabilities, teasing at its fabric with his flute, picking lightly lest he rip the seam. Armed with his contrabass flute in “That Night In Hawaii When I Turned Into A Panther And Started Making These Low Register Purring Tones That I Couldn’t Control … Sh¥t Was Wild,” he’s much more confident. He slurs like Rahsaan Roland Kirk, tweets like Eric Dolphy, sets up a melody, then liquidates it and lets it simmer against the muted vibration of Deantoni Parks’ drum.

Parks, like the rest of the ensemble, is a full participant in the creation of this music, and throughout New Blue Sun, the other instrumentalists show off their ability to spontaneously birth new sounds. In “Ninety Three ’Til Infinity and Beyoncé,” Matthewdavid scrapes and smears crusty grains of noise thick as wheatpaste across the track and Botofasina brings to mind Laraaji’s Vision Songs, Vol. 1 with his homey basement organ in “The Slang Word.” Then there’s Diego Gaeta, whose slowly turning piano runs in “Ghandi, Dalai Lama, Your Lord & Savior J.C. / Bundy, Jeffrey Dahmer, And John Wayne Gacy” are the rotator in the gyroscope, a counterweight that keeps everything from tumbling. He flirts with dreamy realization, pumps a bit of gospel, then slides into a resigned darkness, barely touching the keys; the way his playing sits like a glass turned over the buzzing fly of André’s melody brings New Blue Sun closer to the tragic experiments of Tim Hecker’s Ravedeath, 1972 than jazz or new age.

Niño is a great architect of audio space, but his touch here is more subtle than it is on his Carlos Niño & Friends records. He layers carefully, letting you peek through windows into adjacent rooms, teasing you with the possibility of a party going on but keeping it just out of reach. In the album’s best song, “BuyPoloDisorder’s Daughter Wears A 3000™ Shirt Embroidered,” he sets his own drums deep in the distance and cloaks them in mist, then keeps André halfway between the drums and the foreground, lightly dipping the his flute in distortion. It has the strange effect of making the background of the song more intriguing than the foreground, a sensation deepened by André’s melody. While Mercereau and Botofasina lacquer a sexy, tuxedoed duet for guitar and synth in the front of the song only to be overtaken by a wall of brass, André’s peppy, questioning melody disappears and returns at strange intervals behind it all, blurring out of view and occasionally getting lost in the noise. Even when it’s not there, you feel its presence in the haze; like a Magic Eye piece, “BuyPoloDisorder” is a song whose chaos resolves into unstable patterns over and over again. It’s among the best music anyone on this record has ever created.

Still, the instincts of André and Niño, who produced the album together, occasionally get the better of them. New Blue Sun is patient in a way that Niño’s work often isn’t, and the performances here develop so slowly they sometimes stall out. The stillness of the scene often aims for the muted drama of Hiroshi Yoshimura’s environmental music, but on repeated spins its dramatic tension collapses and can feel tedious at times. On “The Slang Word,” the ensemble struggles to break out of its mutual deference, and the gentleness of André’s prodding starts to feel like time-killing foot-tapping. When it does finally break free, letting out slurry little lines before hopping back into a jittery theme, the song is already beginning its (strangely lengthy) fadeout. This kind of music is built on the relationship between tone, texture, and personality, and as the pieces begin to dilate, it becomes harder to track their development; there are no truly dull moments, but there are dull stretches.

Asking people who have only ever shaken it like a Polaroid picture to clear their minds for 90 minutes of spacey new-age music might be a tall order. Even in the context of the world that birthed it, New Blue Sun is a demanding listen. For all its considerable bright moments, this is a frequently ponderous record, one that suggests a surprising amount of potential but that still demands a lot even from seasoned ears. It’s more successful as a symbol than as an album: It can be incredibly moving to witness one of the most self-assured musicians of all time put himself in vulnerable artistic situations and enjoy figuring out how to navigate them. Even on his handmade flutes, he never lets out the kind of fluid, cocksure flow that sold over 25 million records.

The album’s greatest triumph, then, is its normalcy. It reveals André 3000 to be nothing more than a guy with solid taste in outré music, another Angeleno in deceptively expensive workwear who’s probably been listening to Midori Takada since the YouTube rip. His ability to fit in and play along on New Blue Sun suggests he could easily spend the next 30 years making insular but genuinely interesting records for a small pool of devotees, riding off into well-earned obscurity like Laraaji in a Cadillac. Few stars of his caliber have managed an artistically and personally fulfilling post-fame career without repudiating what they did to become famous—or, worse, rehashing it. That he’s made such a thing possible is a significant achievement.

All products featured on Pitchfork are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.