In the second-last match of continental football in Europe for the 2020/21 season, Villarreal and Manchester United prepared to square off for the UEFA Europa League trophy.

Ole Gunnar Solskjær was leading the Red Devils into his first-ever final as a manager, meaning that this was also his first chance to lift a trophy for the club, and it would also be United’s first major honour since 2017 when they won the same competition. Villarreal, meanwhile, were battling for their first-ever coveted piece of silverware barring the Tercera División and UEFA Intertoto Cup, as Unai Emery was eyeing his fourth Europa League success in five finals.

The Yellow Submarine had an additional incentive as this was a bonus shot for them to qualify for next season’s UEFA Champions League, as their seventh-placed finish in La Liga was only good for an inaugural UEFA Europa Conference League spot. United, meanwhile, had already secured a place in Europe’s premier club competition through their status as Premier League runners-up.

After a close and intense battle, the scoreline was locked at 1-1 winners thanks to Gerard Moreno’s first-half strike, with Manchester United equalising through Edinson Cavani a few minutes into the second period. The game went to penalties, and after each of the 10 outfielders on either side remained faultless, Gerónimo Rulli slotted his effort home before making a save off David de Gea’s effort to win the competition for Villarreal after setting a European competition record of 21 spot-kicks converted in the shootout.

In this analysis, we will explore how the Spanish side’s altered style of play proved vital to their success.

Manchester United’s initial high press

The main pre-match debate among analysts was centred around Manchester United’s pressing, with the question being whether they would go all out and press Villarreal all the way up the pitch or be a bit more conservative and sit in a mid-block. Within a few minutes of the match, the Red Devils delivered a firm answer.

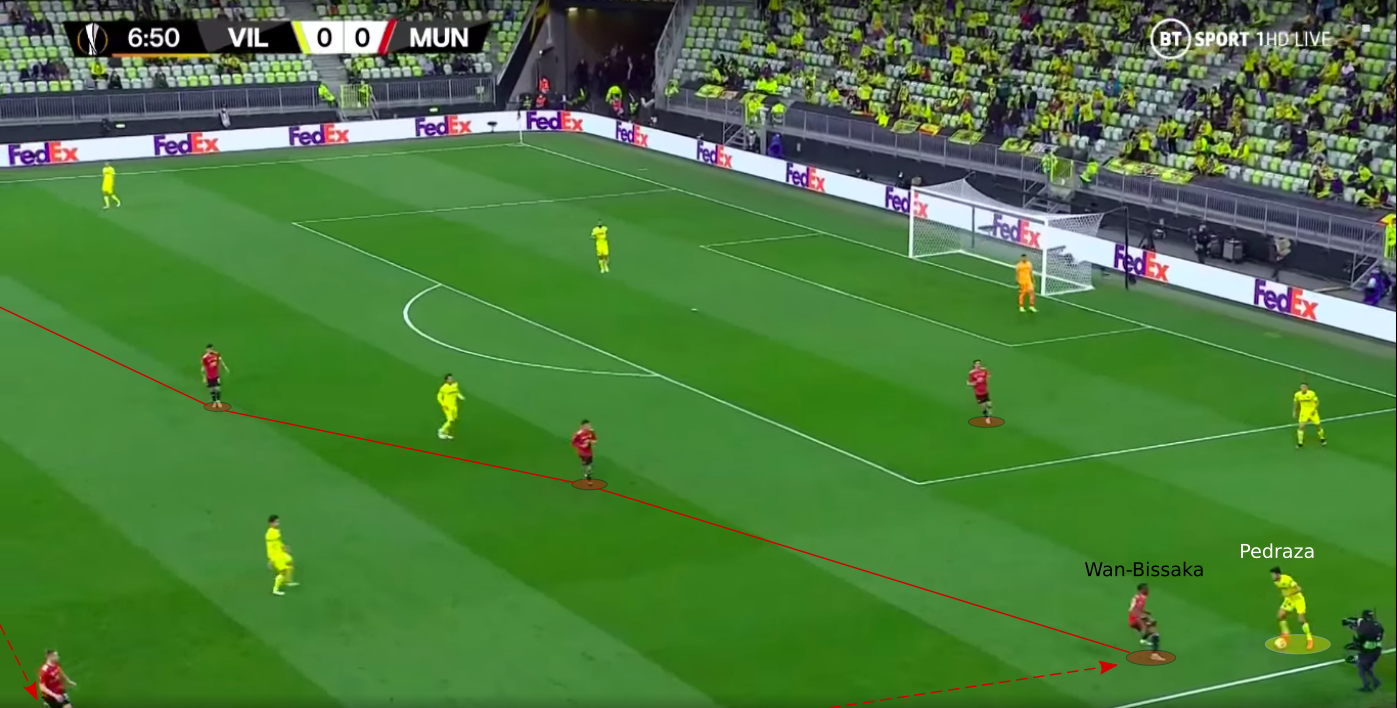

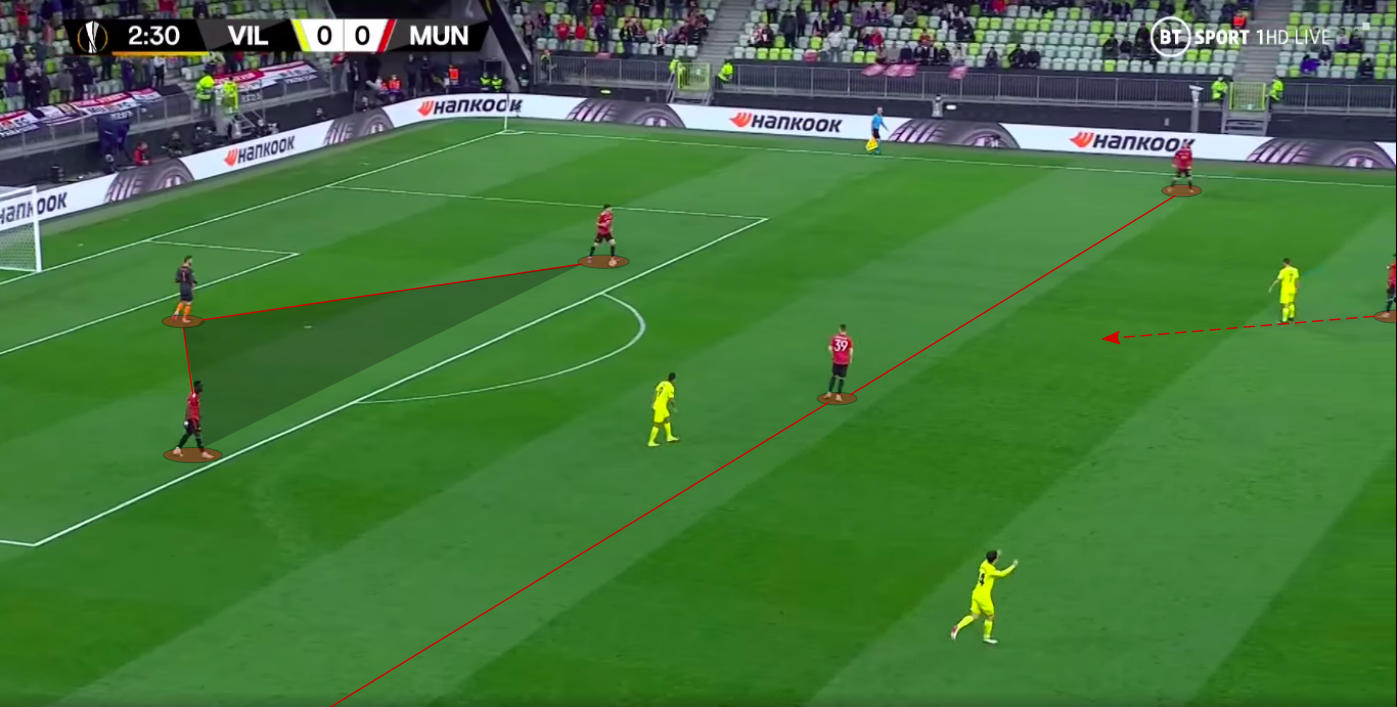

They pressed Villarreal very high up the pitch, especially from static positions such as goal-kicks. The Spanish side mainly tried to play out from the left (partly because they were forced into doing so as Juan Foyth spent a lot of time off the pitch receiving treatment for his head injury), so Aaron Wan-Bissaka pushed all the way up to meet Alfonso Pedraza and effectively create a line of four behind Cavani.

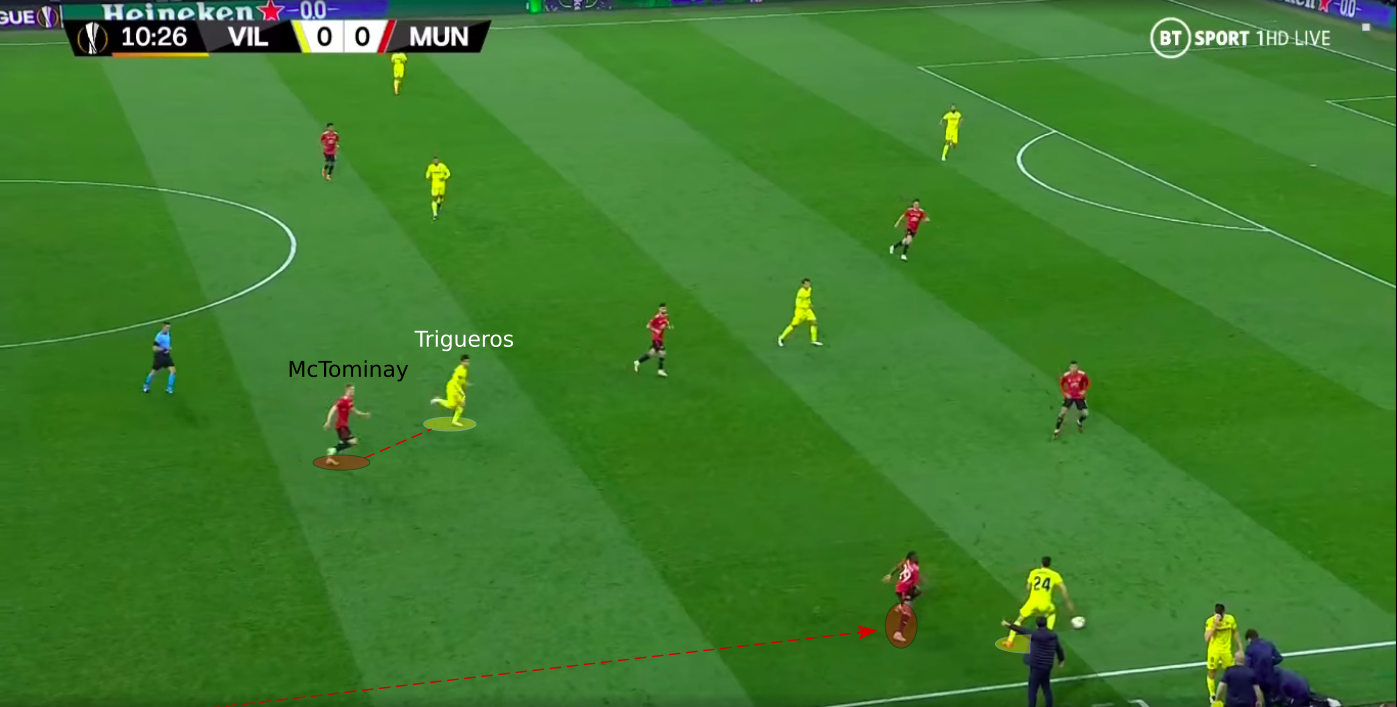

Naturally, this left Manu Trigueros (the Villarreal left midfielder) unmarked by a right-back, so Scott McTominay concerned himself with that responsibility.

This well-executed high press prevented Villarreal from keeping too much of the ball and passing around at the back, denying them an opportunity to play in the style that they usually like to. However, it wasn’t like their game plan set them out to do so anyway, so let us understand that next:

Villarreal’s compact defence

Villarreal have typically played an attractive brand of possession-based football under Emery, but pragmatism overrode that here as they preferred to maintain a very compact defensive structure. This was most likely done with the knowledge that Manchester United’s greatest strengths were in transition and that they struggled to break solid defences down. In fact, in their 11 defeats in all competitions this season, Solskjær’s side saw more of the ball on seven occasions.

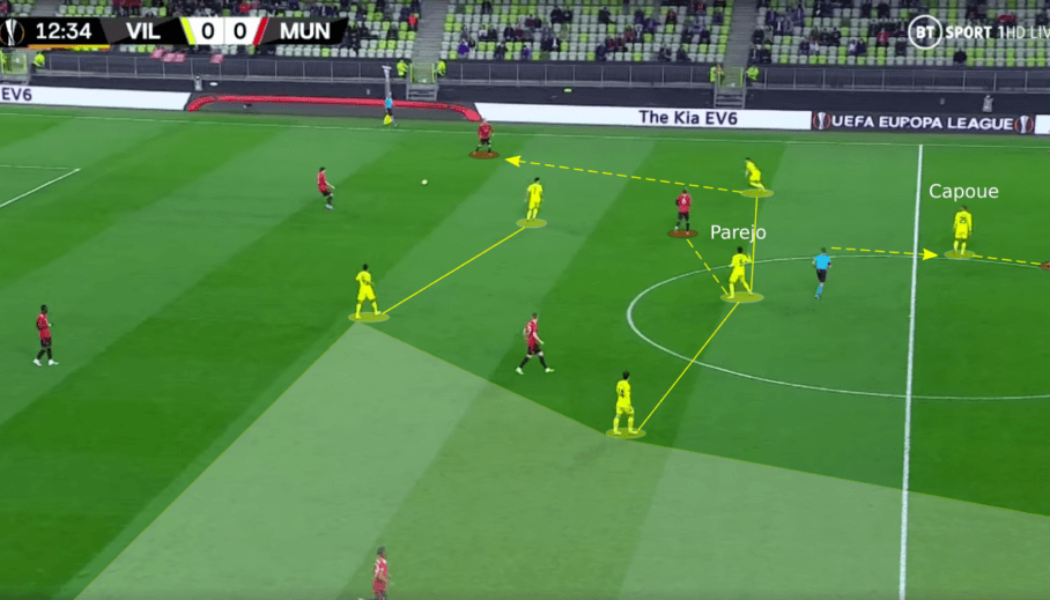

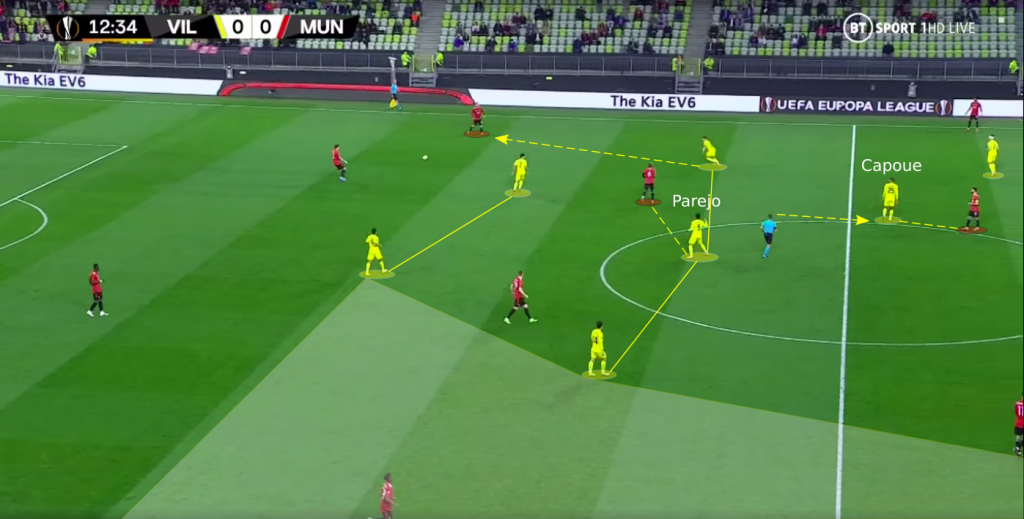

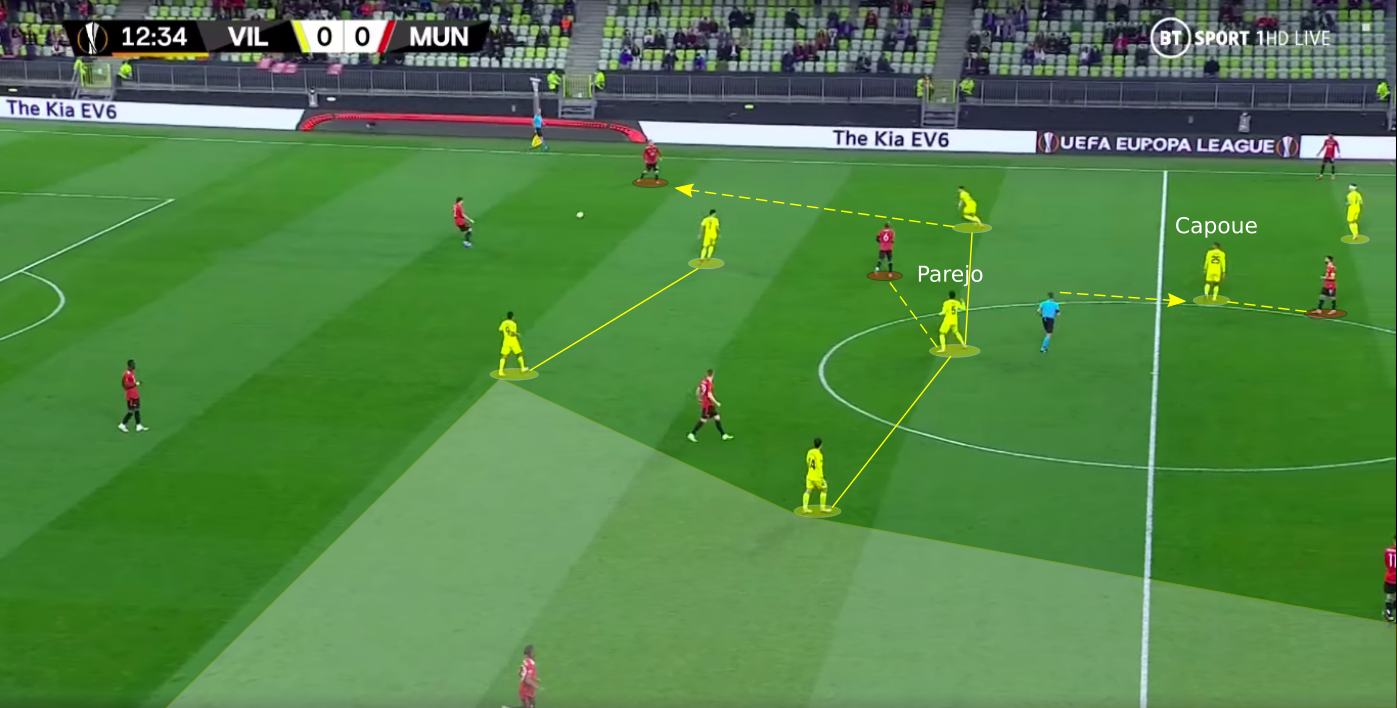

The Yellow Submarine did not drop right to the halfway line from the get-go, though, as they did have some presence in the opposition half in a 4-1-3-2 structure, as Étienne Capoue sat back to mark Bruno Fernandes while Dani Parejo kept an eye on one of the Manchester United double pivot (mostly Pogba). Their shape had a stronger presence on the right side to force Manchester United to progress through Wan-Bissaka and co. on the other flank, which is why Luke Shaw was the only man who was really pressed in possession, with Yeremi Pino doing that job.

To further enforce this, their light pressing from goal-kicks involved curved runs on the right, again forcing United to play the ball out to the opposite side.

This certainly worked, as 44% of Manchester United’s attacks came from their right flank. Wan-Bissaka topped the open-play crossing charts with seven while Mason Greenwood came a close second with six, but since only one of their deliveries found the head of a teammate, it is safe to say that Emery’s decision to let Manchester United progress down the right was smart.

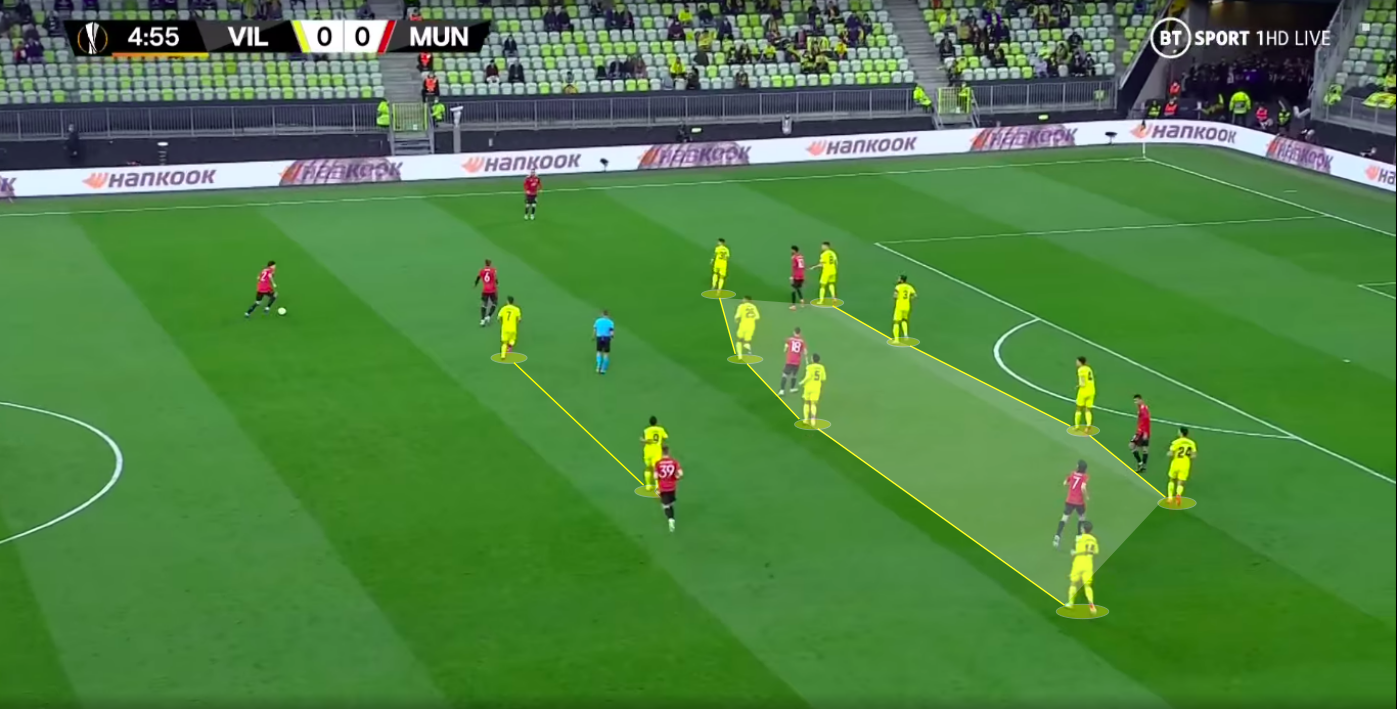

Further back, Villarreal had a very compact 4-4-2 low block, where their primary objective was to minimise the space between the lines and stay centrally compact.

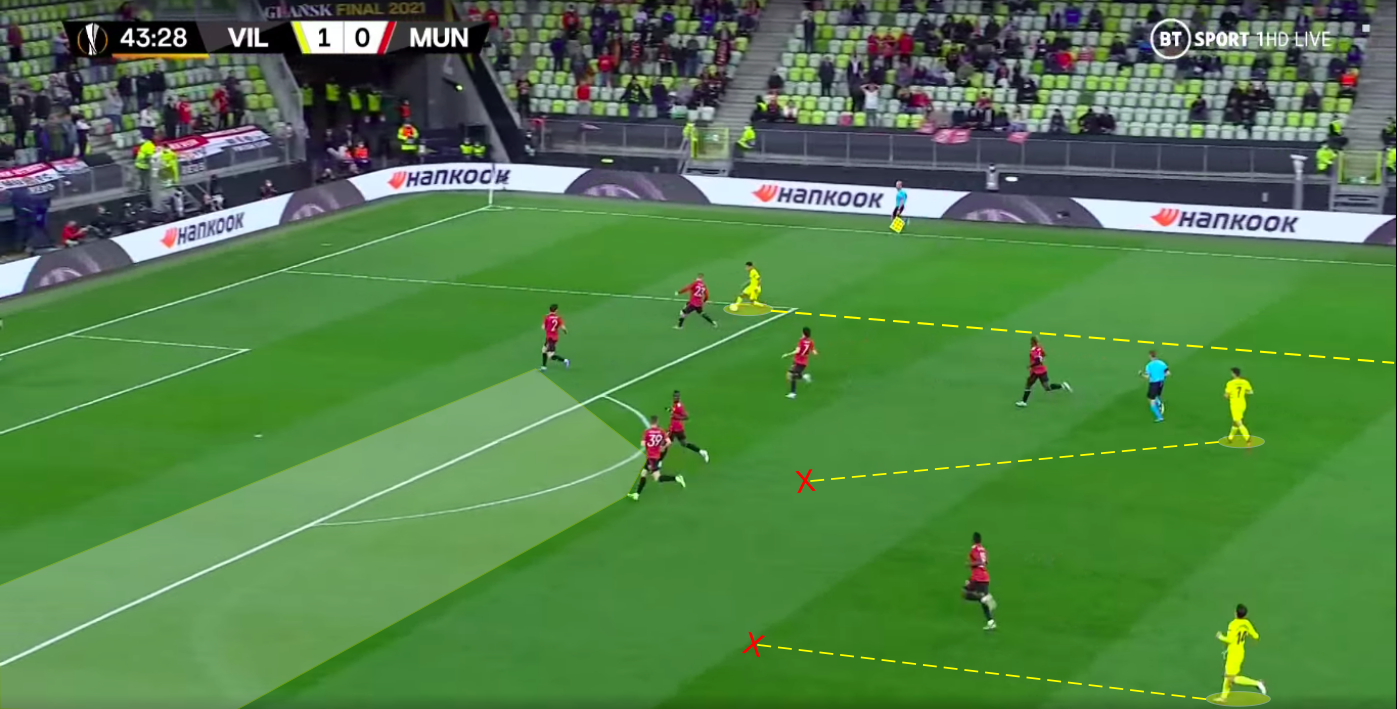

While they certainly did a good job of defending, the side from the east of Spain were absolutely dreadful in transition. Here is an instance from the first half where Pino entered the Manchester United box after carrying the ball forward from almost the halfway line but received no support whatsoever as two of his teammates in the frame showed no willingness to get forward.

Admittedly, they were leading at the time and probably tired after nearly a half’s worth of defending, but such reluctance to commit even two or three men forward meant that they had next to no chance of scoring from open play. Unsurprisingly, therefore, six of their eight shots in the 90 minutes of normal time came from set-pieces, as Manchester United’s biggest defensive weakness was exploited yet again after being magnified due to the absence of Harry Maguire.

Manchester United in possession

With almost 65% of possession in the 90 minutes of normal time and a compact defence against them, Manchester United had a lot of time on the ball to fashion any openings in the Villarreal block.

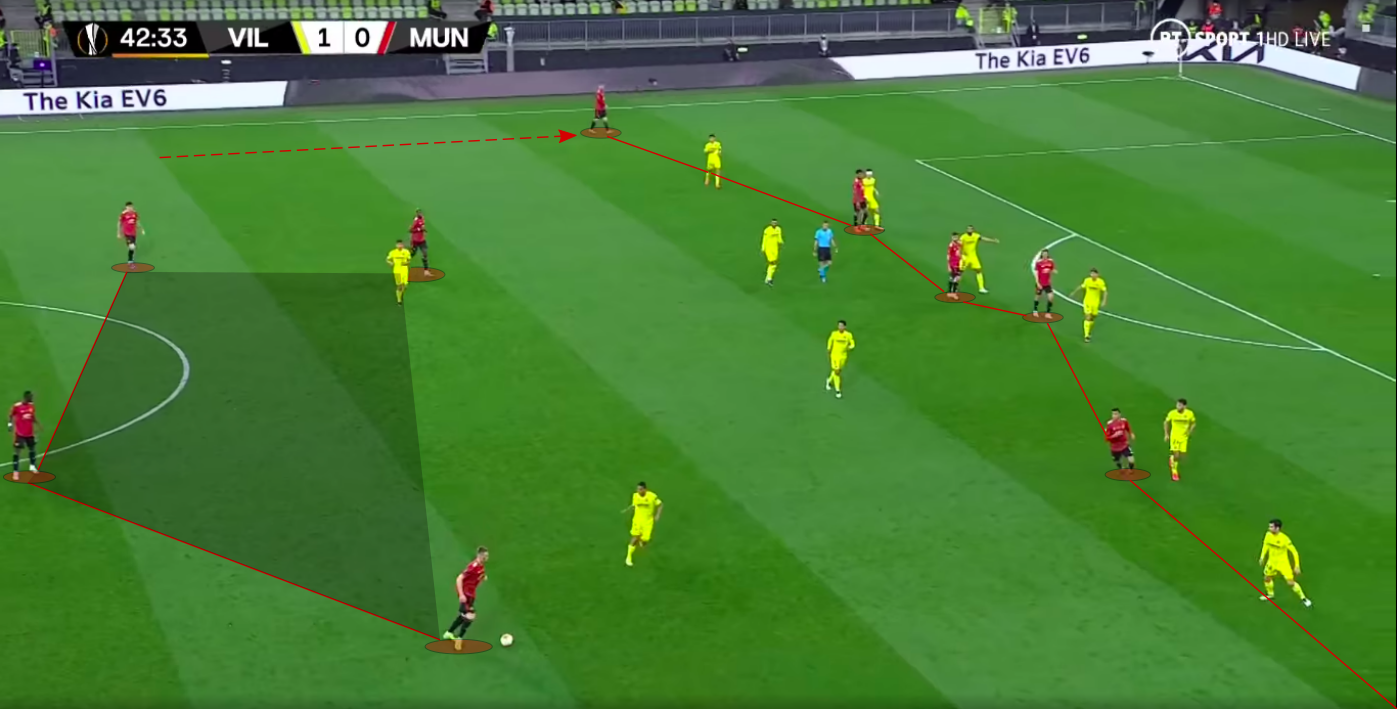

Building from the back inside their own penalty area, United had a 3-3 shape where the centre-backs formed a triangle with the keeper while the full-backs pushed slightly forward and held their width in line with McTominay, who provided a central ball progression option. Paul Pogba was free to drop deep and serve as an additional passing option, but he often stayed slightly forward.

Since Villarreal did not really make ball progression too difficult with their pressing, Manchester United’s next concern was on the other side of the halfway line. They pretty much operated in a 3-1-6, as the full-backs pushed high alongside the narrow front-four, while McTominay dropped to the right centre-back position as he typically does, with Pogba playing the role at the tip of the kite formed using the back-three in midfield.

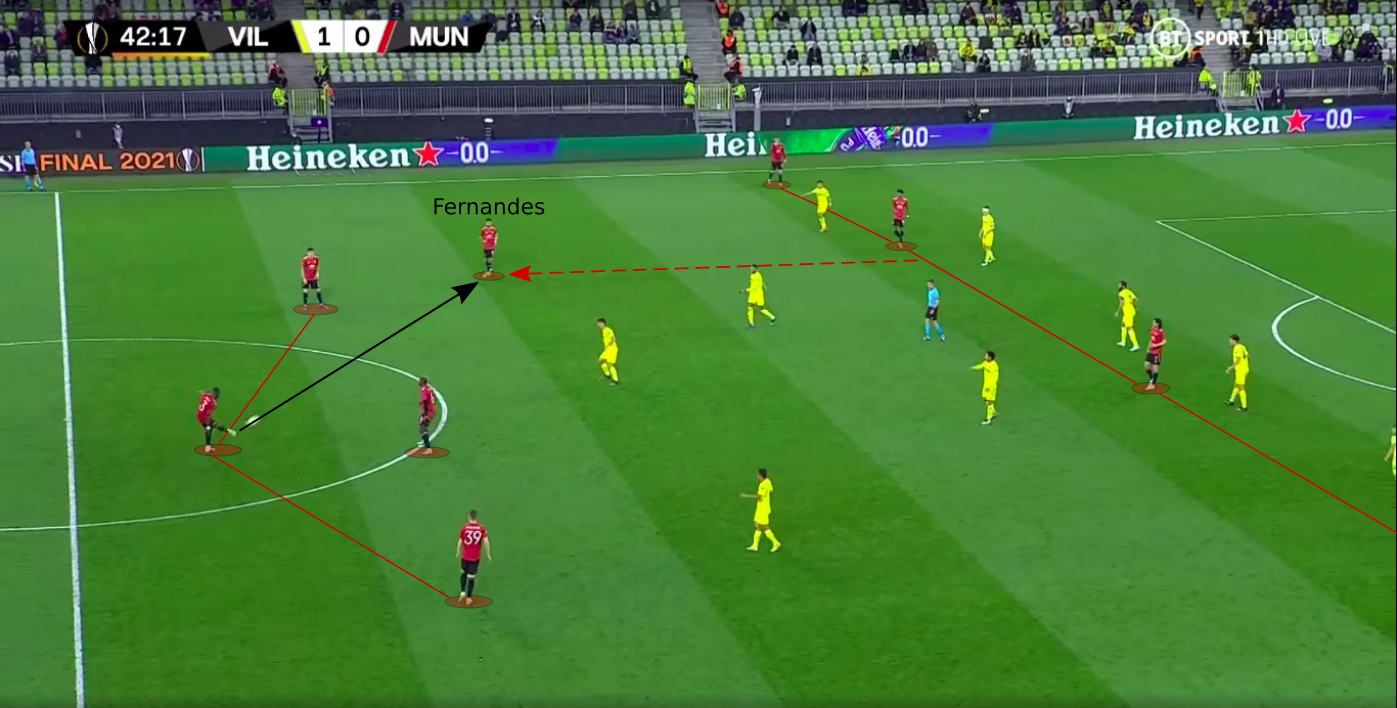

Of course, a six-man front line could easily cause difficulties in ball progression, so Fernandes often dropped back on the left to receive passes and try to take the ball forward.

In the end, though, Manchester United’s goal came as a result of a wayward shot from the second phase of a set-piece, so you have to say that they once again struggled to break down a low block with the lion’s share of possession.

Conclusion

Villarreal and Emery deserve a lot of credit for their clever game plan which played away from Manchester United’s strengths, but another area where the Spanish tactician excelled was in his use of substitutions.

The ex-Arsenal manager made five changes to Solskjær’s zero in the 90 minutes of normal time, with his decisions to bolster the midfield, refreshen the front line and substitute both of his full-backs ultimately proving enough to help his side hold on against a tiring opposition. Ironically, United utilised most of their substitutions to put penalty-takers on the pitch for the shootout, but they didn’t replace a keeper who had failed to stop a spot-kick since 2016, and we all know how that ended.

So, the lack of invention with possession cost Manchester United this trophy, as Villarreal’s shrewd and adaptable tactics saw them lift their first-ever trophy. The Red Devils were, of course, not at their best, but the Yellow Submarine knew exactly how to trouble them, and in the end, just about got the job done.

Stats courtesy Fbref and WhoScored.