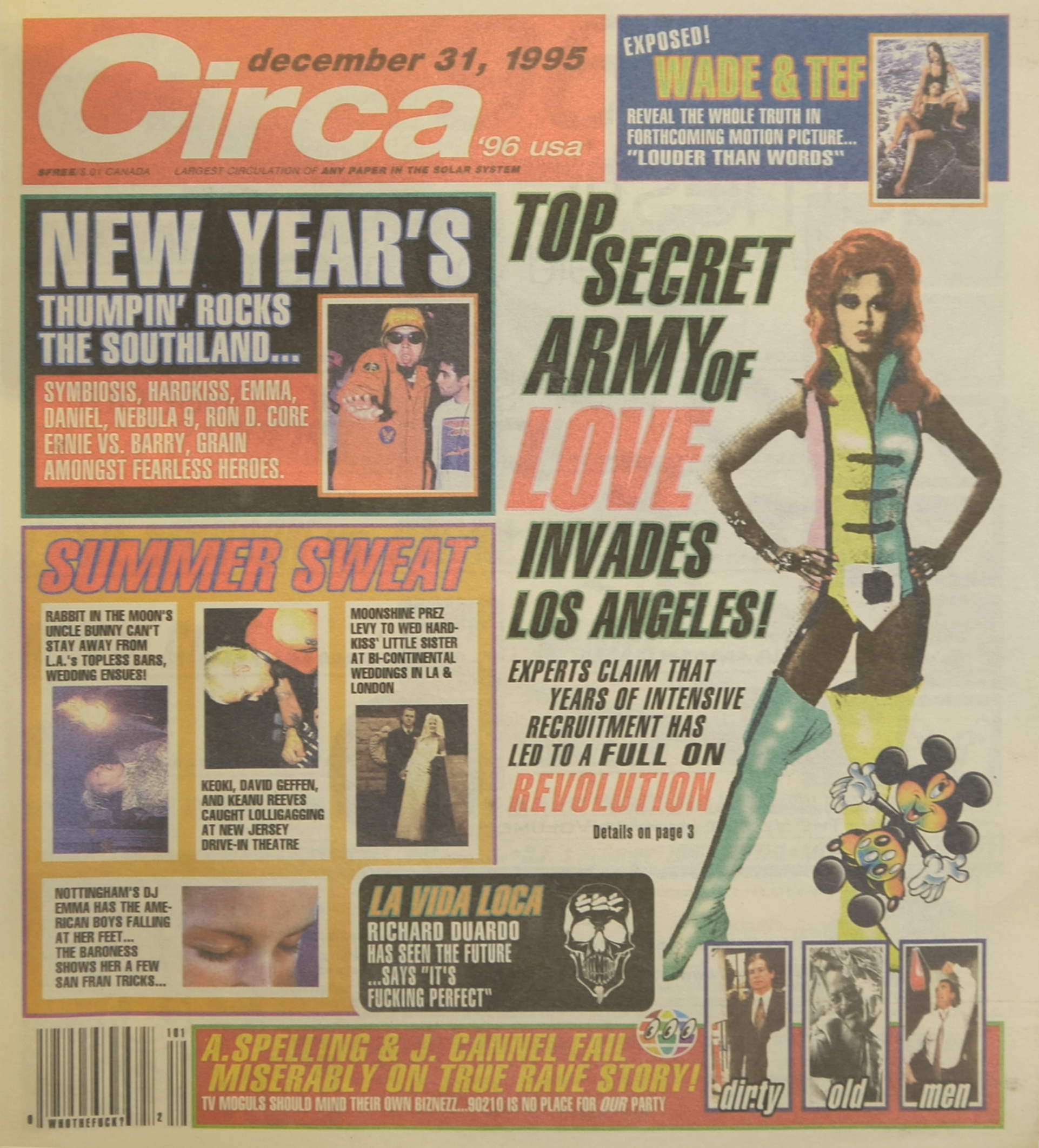

Wade Randolph Hampton and Tef Foo’s “Seventh Heaven” party hadn’t even gotten to midnight when the shit hit the fan. It was New Year’s Eve 1996. They had booked the Grand Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles, and expected 17,000 people to attend. They’d promoted the show with an elaborate tabloid-style flyer and booked artists like Hardkiss, Symbiosis, and Hampton himself to play. But they hadn’t counted on a bad batch of energy drinks.

“Around 9:15, 9:30, it’s like, ‘What’s going on?’ And our manager says, ‘Well, some people are getting sick,’” says Foo of when he first heard about the drink, called Liquid FX and distributed by a man named Daniel Bricker for free to fans waiting in line. “Then around 10 o’clock I’m like, fuck, I have to get on the mic to tell them don’t drink that fucking thing.” It was already too late: At least 30 people had fallen ill, 23 of whom had been rushed to the hospital. Within the hour, the show had to be shut down. “The fire marshal’s like, ‘Guys, I’m gonna run out of ambulances,’” says Foo.

That’s when all hell broke loose. The thousands of fans who either had to leave the party or had never gotten inside in the first place — estimated by the Los Angeles Times to be over 10,000 — took to the streets to vent their frustrations. Police responded in force, in full riot gear, throwing tear gas, and shooting bean bags and rubber bullets. Helicopters circled overhead. Rioters smashed a squad car with a piece of concrete dropped from atop a parking garage, and attempted to flip over a city bus.

“I just remember hearing the crowd stopping at midnight and doing this countdown, and feeling how loud it was,” says Hampton. “There was nothing in the ’92 riots that even came close to that emotion. It was like, ‘Holy shit. They are going at it right now.’”

Such scenes are a rarity in the generally peaceful dance music world, but for a time in the 1990s such unrest was common among the raves of Los Angeles. The city was home to a unique confluence of history, culture, and politics that had explosive repercussions. “There were great promoters, in a creative sense, but there needed to be more planning and infrastructure,” says Philip Blaine, who back then operated his own company, Philip Blaine Presents. Nearly 25 years after “Seventh Heaven,” those riots continue to resonate, with riots and police brutality thrust into the spotlight in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests and the siege of the US Capitol in January.

Simon Rust Lamb was a journalist in L.A. during the ’90s, serving as editor-in-chief for ‘zines like Lotus, Fix, and BPM, and contributing to Urb. “I was definitely at shows where the riot police showed up and they just don’t stand out to me, because that was what was fun,” he says. After becoming a lawyer, Lamb worked as COO and general counsel to Insomniac Events and dealt first hand with city government and the police. “You had an overbearing police department, which still to this day hasn’t been fixed, and basically this idea that dance music and ‘drug supermarkets’ were intertwined,” he says.

Hampton puts things more bluntly: “The L.A.P.D. showed its ass again and again and again,” he says.

Raves were a predominantly underground phenomenon in the U.S. during the early ’90s, with events like Gilligan’s Island on Catalina Island in 1991 (the self-proclaimed “Summer of Love” among L.A. ravers) giving them an early platform in the public eye in Southern California. It garnered coverage on MTV. Hampton and Foo, together with visual artist Richard Duardo, who later called themselves CPU101, held an Olympic Games-themed party called “Circa 92″ at a sold-out Shrine Auditorium, which held 6,000 people, in March 1992. “We had one East side Chicano, one Asian, one Caucasian boy from Chicago. That’s a perfect mix to me,” says Foo of him and his partners. That diversity was reflected in the audience make up, which was heavily Latino. Foo refers fondly to show-goers of the era as the “Benetton generation.”

A week after “Circa 92,” the L.A. Riots erupted over the outcome of the Rodney King trial. Sam “XL” Robson was in Melrose at the time, and later founded the Pure Filth Soundsystem record label. He was convinced that “Circa 92″ would be a “blueprint” for other promoters, but things changed thereafter. “It did quiet down. It fragmented into very small, after-hours [shows],” Robson says. Despite the idealistic attitudes of people like Foo, gang activity helped contribute to the unrest. “This building where you’re about to do this party is actually controlled by a pretty ruthless gang, and if you do not pay that gang off in some way, pay respect to them…then you will have those people showing up and disrupting and causing problems,” Robson says.

DJ Jon Williams, who’d moved to L.A. from the UK after performing at Gilligan’s Island, helped put together a show headlined by Rozalla, then riding high on her No. 1 U.S. dance single “Everybody’s Free (To Feel Good)”. It was scheduled to be held the weekend of the riots. The gig was canceled due to the city’s prolonged curfews, with a later makeup date held over the summer. But the subsequent show, which Rozalla backed out of, was beset by its own trouble when the door money went missing, allegedly due to a robbery backstage. “Events in L.A. could be pretty sketchy across the board,” Williams says. That sketchiness sometimes had to do with the people who put the events on. “Behind the promoter in L.A., there was always an investor. And you never wanted to look too closely at that side of things,” adds Williams.

At the end of 1992, Gary Richards, better known as DJ Destructo and later the mastermind of the HARD cruise and festival franchises, threw a New Year’s Eve party called “Rave America” at the Knot’s Berry Farm amusement park in Buena Park. An estimated 17,000 people showed up and rushed the gate, leading the fire marshal to intervene and shut things down. Fans rioted. Keoki was scheduled to be the headliner that night. “It was crazy. It seemed like there was a lot of tension in the air around that time,” he says. “It felt like the end of the good times.”

Part of the problem, according to Blaine, was that the show was cross-promoted to hip-hop station Power 106 rather than KROQ, which usually catered to more electronic music fans. “I think a lot of that was pushing the expansion a little too fast, too quick, to a group of people that didn’t really understand [the culture]. That made for more of a rough and tumble crowd than what would normally happen at a larger rave,” Blaine says.

The following year, fans rioted again when “Circa 93,” held at a warehouse in Marina del Rey, was shut down by the fire marshal over code violations. “We go outside and there are helicopters flying over. There’s fucking smoke. It’s bad,” says Hampton.

The night before, lighting gear had been stolen from the venue. The show was supposed to be part of a package tour including Aphex Twin, Moby, and Orbital. Paul Hartnoll, one half of sibling duo Orbital, hid in his tour bus with brother Phillip. “We were literally lying on the floor because we didn’t want to get a brick in the head,” says Hartnoll. When he did peek out of the window, he says he saw pandemonium. “It just looked like a scene from some ’80s cult movie.”

He says he’s never seen anything like it elsewhere. He admits that the Marina del Rey riot played into the reputation for “gang warfare” he’d heard about L.A. “It’s one of the very few places in the world where, people like bus drivers and tour managers and people at the venue say, ‘Oh, yeah, don’t leave the building. Do not go in the park over there.”

Party promoters were at least in part responsible for some the troubles. Gerry Gerard, Nine Inch Nails’ manager, attended some area raves. “They’d just take over a factory or warehouse, just go in and do the event — before the police even found out it was going on, sometimes,” Gerard says. As someone accustomed to traditional concerts, the environments came as a shock. “It was kind of terrifying,” he admits. “You’d end up walking along a gangway and then you come to the end up in the air, looking down at nowhere.” Hartnoll saw similar hazards at “Circa 93,” where he says the stage consisted of two flatbed trucks full of gasoline. “It was always the fire marshals that people were concerned about,” insists Williams. “They were the ones with the capability to shut it down.”

Enterprising promoters often had little choice but to book shows in shady venues, as they struggled to get clearance for conventional locations. “From a police perspective it’s like, ‘oh, well, these events are happening in unsafe places’, but they weren’t allowed to happen in safe places,” says Lamb, whose specialty at the time was reporting on desert parties. “Event management in that scene was a novel skill. People were learning on the go,” he adds. For that reason, Blaine felt it was key to go outside dance circles to help the industry grow and become more legitimate. “The majority of my staff were from the concert and traditional festival scene,” he says.

Still, by the time CPU101 organized “Seventh Heaven” at the end of 1996, electronic music had gained a much stronger foothold in the city. Hampton and Foo shifted focus after “Circa 93″ and moved towards its New Year’s Eve format in 1995, then aimed to go bigger with headliner Hardkiss riding high on the release of their highly influential compilation Delusions of Grandeur. “I did a lot of town hall meetings with police and ambulance personnel to get permits,” says Foo of the enhanced preparation that went into these later shows. “But as far as people getting sick off smart drinks? I didn’t have a protocol for that.”

Confusion took over as fans continued to arrive for “Seventh Heaven” only to discover it had been called off. “A lot of people didn’t know what happened by the time it gets shut down…” says Hampton. While the rioting took place, Blaine recalls sick fans were laid out in a nearby parking lot, with color-coded toe tags used to indicate the severity of the patients’ conditions. Meanwhile, some people — “ambitious hustlers,” as Hampton puts it — handed out hastily made fliers for pop-up parties held in nearby hotels at the rear of the conflict.

Dance music was by now moving in a different direction. In June 1996, Organic was held at a ski resort in San Bernardino, and is now recognized as the first major festival for dance music in the L.A. area. It attracted 6,500 people and went off without any notable disruption. Gerard, Blaine, and Insomniac Events founder Pasquale Rotella joined forces to help organize it. “Back then it was just chaos. Which was part of the fun, I think — like, the fact that it was just so unpredictable what could happen on any given night,” says Lamb. But Organic represented a change of direction that foreshadowed the EDM festival behemoth that emerged in the 2000s.

“One of the reasons Organic worked was it was bands. It wasn’t a DJ lineup. So, the pitch was a little different,” says Lamb. But, he adds, “it was a rave for anybody that was in the rave scene.”

In the years that followed, Blaine took on senior roles with Coachella, which was split almost evenly between electronic acts and live bands in its early years, and Insomniac Events. (Hampton now works for Coachella as well.) In fact, Insomniac, which launched its marquee Electric Daisy Carnival at the Shrine in 1997, took over CPU101’s NYE slot at the Grand Olympic in the aftermath of “Seventh Heaven.” “I did the right thing. I handed over the keys,” says Foo.

But the rioting wasn’t out of the blood system for L.A. fans. In the summer of 1998, riot police were deployed to the site of Insomniac’s Nocturnal Wonderland, held in San Bernardino. James “Disco Donnie” Estopinal Jr. was a co-promoter of the event. “There wasn’t necessarily a riot, per se,” he says. Based out of New Orleans, this was his first venture into L.A. “We only had like one gate open and all of a sudden 20,000 people were out in the parking lot trying to get in and buy tickets. It was just mayhem. I mean, they literally had to tear gas the line.”

“It’s not really that they want to destroy things,” Hamptons says of L.A. ravers, equating the confrontations with riots that took place at punk shows on the Sunset Strip in the ’70s and ’80s. “They’re not mad. They’re there to dance and party. And in this town, if they’re told they can’t do that, they have a tradition of tearing the neighborhood up.”

He adds encouragingly: “They don’t necessarily want to hurt anyone.”