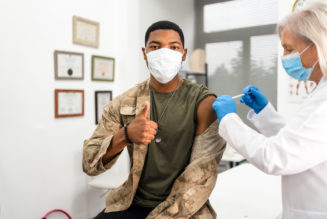

- New research shows high levels of lean muscle might help protect against Alzheimer’s disease.

- However, further research is necessary to understand if this connection is causal.

- To achieve lean muscle mass, experts recommend resistance exercises and a healthy dose of dietary protein.

Previous research demonstrates the connection between

According to a study recently published in BMJ Medicine, high levels of lean muscle could help ward off Alzheimer’s disease. However, the study authors noted that more research is needed to understand the biological processes behind it.

In this study, researchers collected information on the genetic data, lean muscle mass, cognition and health data of 450,243 participants from the U.K. Biobank. They then looked for genetic associations between lean muscle mass and genetic variants using a technique known as Mendelian randomization.

Researchers used bioimpedance, an electric current that flows through the body at different rates to measure the amount of lean muscle and fat tissue in the arms and legs. They then found 584 genetic variants linked to lean muscle mass, although none of these were on a region of the genome known to code for a gene associated with increased Alzheimer’s disease risk.

However, researchers did find that those people who had high levels of lean muscle mass and associated genetic variants, the more the individual’s Alzheimer’s risk decreased.

These findings were verified in another cohort of 7,329 people with Alzheimer’s disease and 252,879 people without, researchers measured the amount of lean muscle mass and fat tissue in the torso and whole body.

Results showed that lean mass was linked with improved performance on cognitive tasks, but this connection didn’t explain the protective impact of lean mass on the development of Alzheimer’s.

“This study supports current recommendations to maintain a healthy lifestyle to prevent dementia. It is a hopeful finding which gives patients agency in their neurologic health,” Iyas Daghlas, one of the study authors, told Medical News Today.

For the next steps, “clinical intervention studies are needed to confirm this effect,” Daghlas added.

“This study is well aligned with other recently published research that showed in the years before an Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis there is a significant decline in lean muscle mass and strength,” said Karen D. Sullivan, Ph.D., ABPP, board certified neuropsychologist.

“Wanting to go beyond just a correlation relationship, these researchers wanted to understand cause and effect between Alzheimer’s risk and muscle mass,” she added.

“The diseased brain cells in all dementias, including Alzheimer’s, show severe mitochondria dysfunction; this is what happens when neurons can’t produce enough energy to function or stay viable due to whatever disease is causing dementia,” Dr. Sullivan said.

“Mitochondrial dysfunction is the common denominator, a shared characteristic of all diseased biological systems, so it’s likely not just an Alzheimer’s-specific finding.”

Mitochondria dysfunction is also seen in skeletal muscle loss, as those muscle cells cannot take in enough, and in several chronic diseases, like cancer, deconditioning, sepsis, etc. Lean muscle mass is an indicator of healthy mitochondria functioning, Dr. Sullivan explained.

When muscle cells or brain cells have healthy powerhouse mitochondria supporting their function, they thrive. When the opposite is true, they die. We know that reduced muscle mass reduces the quality of life, risk of falls and fractures, and mortality, Dr. Sullivan added. We can now likely add cognition to that list.

Proteins, known as myokines, may play a role.

“We speculate that the association we describe could be mediated by the effect of myokines,” Daghlas explained.

“Myokines are proteins released by muscles that affect other tissues. They have been shown in experimental studies to be induced by exercise and to positively influence brain function,” he said.

Aside from the potential brain benefits, there are many health advantages of having lean muscle mass.

Dr. Joseph C. Maroon, clinical professor, vice chairman, and Heindl scholar in neuroscience at the Department of Neurosurgery at the University of Pittsburg, recommends resistance exercises with weights, bands, and pleiomorphic exercises.

He also suggests a healthy source of dietary protein, supplementation with B-hydroxy B-methylbutyrate (myHMB).

“This is a naturally occurring substance that helps the body build lean muscle mass and manage a healthy weight. B-hydroxy aids in muscle recovery after strenuous exercise, increases athletic performance, and builds muscle and strength,” he said.

The main drivers of muscle mass are the right diet, the right type and frequency of exercise, the proper amount of rest, and stress management, Dr. Sullivan noted.

Here are the guidelines she recommends:

Exercise: 4-5 short sessions of strength training per week. This will result in more lean muscle mass than 2-3 longer cardio workouts per week.

Diet: Focus on reducing insulin resistance by lowering carbs and increasing protein, the build block of muscle.

Sleep: 8-9 hours per night if continuous or near continuous sleep is needed to properly recover from this type of training.

Stress management: Chronically high stress can derail any self-improvement plan, with the increase in inflammation and blood sugar caused by stress hormones like cortisol. High levels of cortisol over time also cause prolonged muscle tension and a build-up of lactic acid that can limit muscle growth. The easiest way to reduce chronic stress is to move your body more, get outside, eat more whole foods, be an assertive communicator, and connect with your purpose.

For this study, researchers only looked at lean muscle mass. But there are other factors to take into consideration.

“The researchers did NOT measure inflammation markers and insulin resistance, which have higher levels in fat tissue of the protein harmful to brain health, amyloid β,” said Maroon. “This likely reduces the significance of their conclusions.”

Additionally, “while their positive finding was statistically significant, the effect size was modest in lean muscle mass reducing the dementia risk and only explained 10% of the variance,” said Dr. Sullivan.

There’s still more research to be done to determine the connection between higher lean muscle mass and a lower risk of Alzheimer’s.

“For now, people with lower muscle mass tend to be obese, which is a risk factor for type 2 diabetes,” said Nancy Mitchell, a registered nurse.

“We call Alzheimer’s diabetes of the brain because high blood glucose is suggested to damage the nerve endings in the areas of the brain most affected by cognitive decline. So, it’s possible that the connection is really between a lower risk of obesity and diabetes. This, in itself, might be a limitation to the study because there’s still room for more specificity. Correlation doesn’t always mean causation.”

— Nancy Mitchell, registered nurse