Dyson invited me to spend two days inside its hyper-clean universe to see what’s next and why it’s trying to scrub every hidden bit of filth from our homes.

Share this story

The Dyson Kool-Aid is powerful. For a week after touring Dyson’s Singapore headquarters, soaking up talks and presentations on filth and viruses, I can’t help but feel like my home isn’t clean enough. I’d always known that dust mites were an inevitable problem in all beds, but I’d never really had the urge to learn about how they defecate in the unreachable bowels of my mattress, filling our homes with allergy-causing poop. Thanks to Dyson, I now spend way too much time thinking about microscopic crap that cloaks my body as I sleep.

“Dust is a problem,” announces Zerline Lim, an associate principal engineer from Dyson’s Malaysian labs, during an hour-long presentation on dust and air science. For Dyson’s team, though, it’s less of a problem and more of a standing invitation — dust, to them, is a gateway into people’s lives.

You don’t need to tell me twice — I’m the sort of person who wakes up with watery eyes and pops a Zyrtec every day — and today, Dyson is unveiling a new range of cleaning products to address that sort of thing. It’s an unsurprisingly pricey set of gadgets that does more of the same robust cleaning and air filtering that the company has become known for. But this new set of toys is being introduced to a pandemic-driven world where our concerns around dust, air pollution, and germs have stoked interest in better and more powerful cleaning solutions.

It’s a sweltering Tuesday morning as I walk into the vast, cool interior of Dyson’s global headquarters in Singapore — an Edwardian-style brick behemoth that was once the St James Power Station, Singapore’s first power plant. After a stint as a warehouse, in 2006, the location became a sprawl of cheesy harborside nightclubs with flashy cars and obnoxious drunks. Now, it’s pristine and quiet, a serene corporate haven of concrete, glass, and open-plan office spaces nestled within the building’s original industrial steel skeleton. On the ground floor’s communal area is a small copse of trees, which I’m told contained some rather unhappy snakes when they first arrived.

Inside, I take a mini-tour of Dyson products on display in the cavernous reception area, which includes a functioning prototype of its canceled electric car — a hulking, boxy SUV that would have been manufactured in Singapore. There’s even a Recyclone, a vacuum cleaner made entirely of recycled plastic that apparently remains a real catch among vacuum cleaner enthusiasts due to how few were ever produced. The common thread between these failures, at least how they’re spun, is that Dyson was too ahead of its time. The Recyclone came out in 1995 when “there was a perception that because they were made out of recycled plastic, they weren’t as good,” says floorcare VP Charlie Park. The car project, which involved costly original designs, wasn’t commercially viable. It was the same story for Dyson’s short-lived Contrarotator washing machine. In 2023, things are different for the technologically bold and environmentally sustainable. Fast failures and clean green consumerism are positive selling points amid a climate crisis.

We’re here to learn about the “future of clean” and the company’s new slate of products. Although many Dyson products already have HEPA filters, the company has, understandably in the wake of the pandemic, leaned even harder into virus filtration and granular cleaning features for the place many of us were confined during the first year of covid and continue to spend most of our time.

After we take seats on a set of college quad-like steps in the former Turbine Hall, CEO Roland Krueger takes the stage to lay out James Dyson’s vision: to find solutions to problems that others cannot or will not solve. On the simplest level, the company is attempting to align cleanliness with relentless progress and a sense of personal and public good. To this end, Krueger explains, Dyson’s long-term plan for the “future of clean” asks customers — in an unmistakably polite, British way — to learn to “[disrupt] ourselves internally,” which largely means using the Dyson app to optimize their cleaning.

Even as the pandemic has amplified my most germaphobic qualities, it’s hard to imagine being so concerned about my home’s cleanliness that I’m willing to download yet another app and consider a new arsenal of pricey gadgets (least of all, the Bane mask-adjacent Dyson Zone). For the past few years, my housekeeping habits have revolved around a big weekly clean — I air my linens, scrub the bathroom and kitchen, dust shelves, vacuum with an old Dyson V10 Fluffy, and mop the floor. It’s been working just fine, though to be fair, a one-bedroom apartment (with a cat) is a far more intuitive and manageable cleaning situation than a house with children.

Dyson claims that people have become more house-proud in the covid era, though we’re far from being truly clean: “only 41 percent” of people have a regular cleaning schedule and 60 percent “admit to only cleaning when they see visible dust or dirt,” according to the company. It makes sense, then, that Dyson’s flagship invention, the clear bagless vacuum, lets you see exactly how much dirt is being removed from your floors — a constant reminder that you ought to be using it more or a gentle suggestion to upgrade to its new line of laser-enabled stick vacuums.

But there’s always room for improvement. Like the Six Million Dollar Man, Dyson has the technology to improve its cleaning tools beyond what they once were: better, stronger, and more suctiony. And so, we meet Dyson’s new lineup of cleaning products. There’s the Dyson 360 Vis Nav, a D-shaped smart robot vacuum that can hug corners, and the Dyson Purifier Big + Quiet Formaldehyde, a HEPA-standard, CO2-sensing air filter for large spaces that mimics the feel of outdoor breezes by employing a scaled-up version of the same Coandă effect used in the Dyson Airwrap. (It’s a bit upsetting to see “Formaldehyde” in a fan name since it’s usually associated with dead people, but formaldehyde is, apparently, something we should all be aware of in our homes, and this model filters it out.)

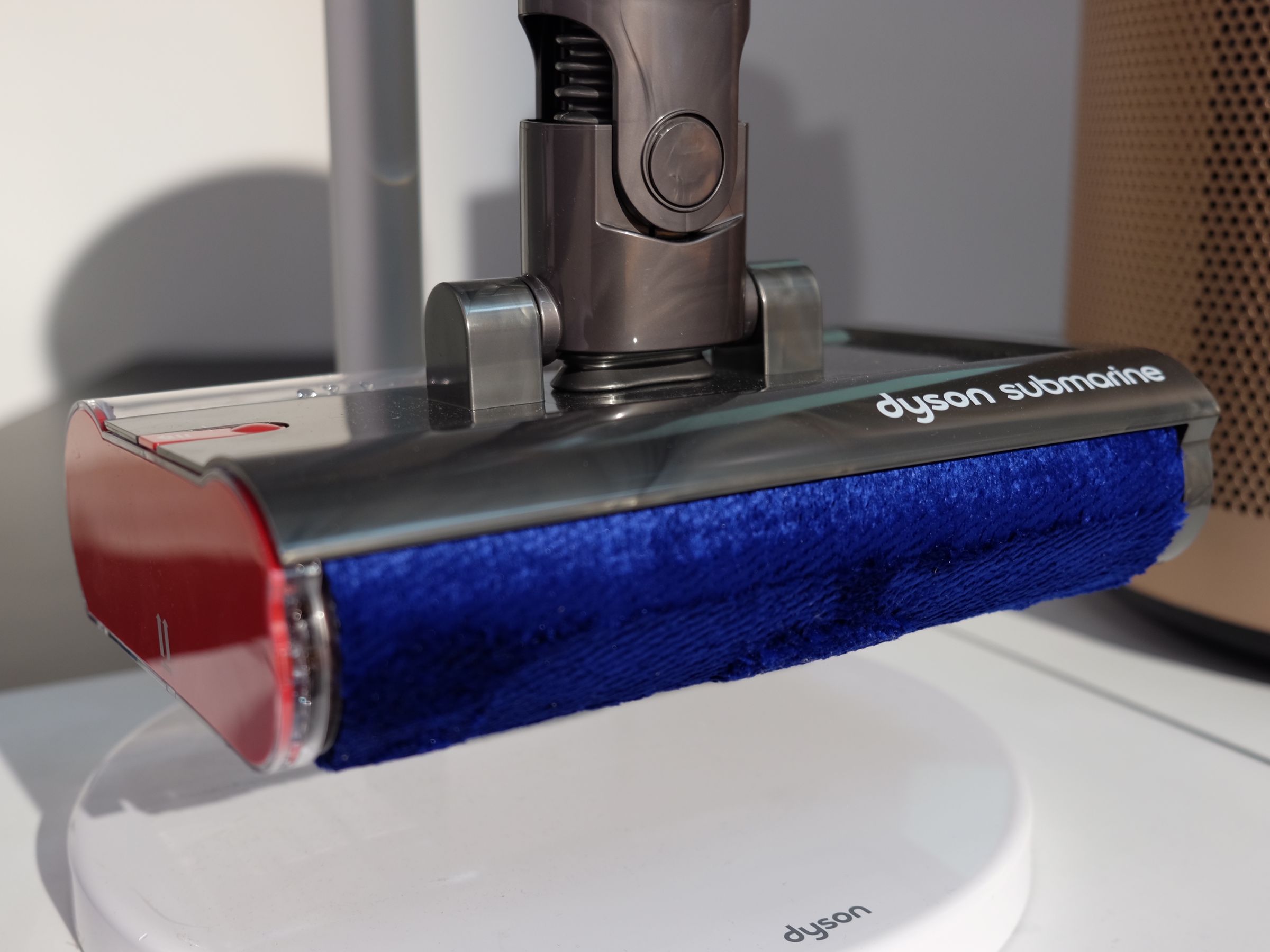

There’s also some new tech for stick vacuums. Dyson shows us the Submarine, an admittedly impressive wet roller head attachment — only available on the company’s new vacuum models — that effortlessly sucks up a blotch of ketchup on a swatch of rug liner. And finally, there’s a new crop of Gen5detect stick vacuums, which supposedly mark the first time Dyson can make a virus filtration claim on its products thanks to a “whole-machine HEPA” filtration system that captures germs and dirt and prevents them from escaping back into the home. Pricing and availability is TBD on most of these new products, but the new Gen5detect models will start at $949. The company’s demo of the new vacuums becomes a source of deep personal horror for me: we’re shown how it sucks up a grainy pile of dust (an analog for dust mite feces) through six layers of fabric. It’s all a logical continuation of Dyson’s pursuit of engineering perfection in the commodity-driven world of home care.

It’s especially interesting to see Dyson unveil the Vis Nav in Singapore, where robot vacuums with mop functions have been common for several years. This mop-less robot is the first robovac that Dyson will be selling in the US in years, which I’m repeatedly told has prohibitively different cleaning requirements than other countries. Besides the larger home sizes, American complications are mostly stairs and rugs, which are features of many British homes, too (though that didn’t stop Dyson from releasing the tall layer cake-like 360 Heurist in the UK). Vis Nav improves on the formula with its corner-hugging ability and powerful suction. But it still feels more like a bonus luxury than a must-buy staple. According to principal robotics engineer Antony Waldock, the robot is a great complement to regular vacuuming rather than a full-fledged replacement. At Dyson prices, that’s a lot to ask from the average homeowner.

The world of Dyson, at least what we’ve been allowed to see with an exquisitely prepared cohort of engineers, is exactly what you would expect from the Rolls-Royce of vacuum cleaning companies. Its language is extremely fixated on the degree of cleanliness people need, a valid concern in a post-pandemic world. But for a company so obsessed with eradicating germs and dust, it might have had better precautions for a close contact global press event where I could count the number of masked people on two hands. During a dust and air science presentation, we’re told that despite having “come out of the pandemic,” there are still large concerns about viruses indoors and in the home. Yet the Big + Quiets remain relegated to their designated corner, rather than being employed to ventilate the masses of international visitors sitting together indoors.

When it comes to cleanliness anxiety, CTO John Churchill believes that customers can make up their own minds about how dirt or germ-free they want to be. He says Dyson’s focus on fact-based research balances out a “world with lots of information” so that customers feel empowered to make up their own minds about how much energy (and money) they need to devote to cleaning. “If you look at really the core of our company, that engineering culture is around people looking for information, researching, making their own minds up. I think we would say our position from an education perspective is to inform people,” he says.

The next day, we visit Singapore Advanced Manufacturing, Dyson’s fully automated, minimally staffed motor manufacturing facility where production runs 24/7 with the help of mobile Omron robots. As we inch between rows of glass-cased machine lines, the engineers’ basic explanations are drowned out by the relentless drone of balancing stations, magnetizers, and conveyor belts. Next, we tour a second Dyson facility, including a semi-anechoic chamber to perform sound tests, a glimpse at how Dyson tests human hair for the Supersonic and Airwrap (which I’m emphatically told is ethically sourced from the UK), and a disappointing look at a laser in a fluid dynamics lab that isn’t allowed to be turned on. When another journalist asks if it’s true that people will lose balance and fall over in a darkened anechoic chamber, we’re told yes, but nobody takes my request to try this seriously.

One of Dyson’s most understated yet critical selling points is its lean engineering approach, which, according to the company, is an intrinsically sustainable process to “do more with less.” To create a sense of moral desirability for something as mundane as a vacuum cleaner is, whether you like it or not, tremendously clever; it’s a highly effective way to extrapolate personal household cleanliness into a much broader global concern about environmental purity. At the same time, Dyson labs use specially prepared dust flown in from Germany to keep its tests consistent, gathers 64 products from around the world — like Japanese cat food and UK cereal — for use in “pick-up” tests for their vacuums, and brings together around 30 different resins for a single vacuum body. Commercial and industrial sustainability is a far cry from the kind of individual responsibility we’re trained to think of; as a result, when I think of the “right” vacuum to buy, more often than not, I’ve historically always thought of the right choice as a Dyson not just for their perceived effectiveness but also for the company’s “better, cleaner living through engineering” image.

“[Sustainability] is a very thoughtful space, which is why we don’t communicate it a lot, because it’s very complicated,” Churchill says. “We’ve got loads of examples of little things we’re doing. The ultimate thing for us now is to bring that all together for Dyson to have a more comprehensive position on sustainability that people can understand.” Fortunately for Dyson, no one seems to care if the company can’t communicate it well enough because the Dyson name already commands the right sort of attention from an enthusiastic design-minded demographic. That Dyson also seems to be eco-friendly — or at least as close to eco-friendly as you can be in the appliance business — is more of an ambient, reassuring vibe.

What I do understand is that cleaning products today, environmentally conscious or not, aren’t built like they were in my parents’ generation, and seeing the amount of work and resources that go into Dyson products is at once inspiring and exhausting. Park, the floorcare VP, believes that the expectations and perceptions of “acceptable lifespans” aren’t just generational but also location-based. “If you go to Germany, for example, the general behavior there is to invest more and a lot less regularly, compared to America, which is the exact opposite extreme where people will generally pay for something cheaper but are happy to replace it more regularly,” he says. Somewhere along the way, advertising succeeded in conflating newness with cleanliness — that the idea of an old but well-maintained and functional machine pales in comparison to a shinier but less robust one.

So, what is the future of clean for Dyson? It seems more of the same, except with a 30-year plan to connect all its products together under a centralized MyDyson app to gather data and offer tips. I can’t help but feel a little disappointed, even if I found myself enthralled by the Submarine demo or marveling at how far the Big + Quiet Formaldehyde (what a mouthful) seemed to project its jet of air. This is not my beautiful house. This is not my beautiful Jetsons wife. This is not something I can imagine myself needing, at least not for my cleaning purposes.

When it’s all over, I come home to my relatively clean apartment. Not being able to see every speck of Schrödinger’s dirt makes me question my own relationship with cleanliness, anxiety about recycling efficacy, and Dyson’s outwardly spotless reputation as the go-to company for quality home care. Do I need a new vacuum? Absolutely not, but it doesn’t stop me from thinking about the security of a HEPA-standard replacement. When asked about potential conflict between robot vacuums and Dyson’s stick vacuums, Park poses a simple question that inadvertently sums up what Dyson is really trying to sell: “when you roll it right back, the key question is ‘do you want to vacuum-clean your home or would you rather it just happen magically?’” My answer to that, with the image of the fabric-wrapped layers of dust mite feces still burned into my retinas, is simple: I’ll choose magic, if only it didn’t come at such costs.

Photography by Alexis Ong for The Verge