Early this morning, a small NASA spacecraft about the size of a microwave embarked on the beginning of a four-month-long journey to the Moon, where it will eventually insert itself into a unique, elongated lunar orbit that no NASA mission has visited before. The spacecraft’s goal is simple: test out this particular orbit and see what it’s like. That’s because it’s the same orbit that lunar-bound astronauts could use in the coming decade.

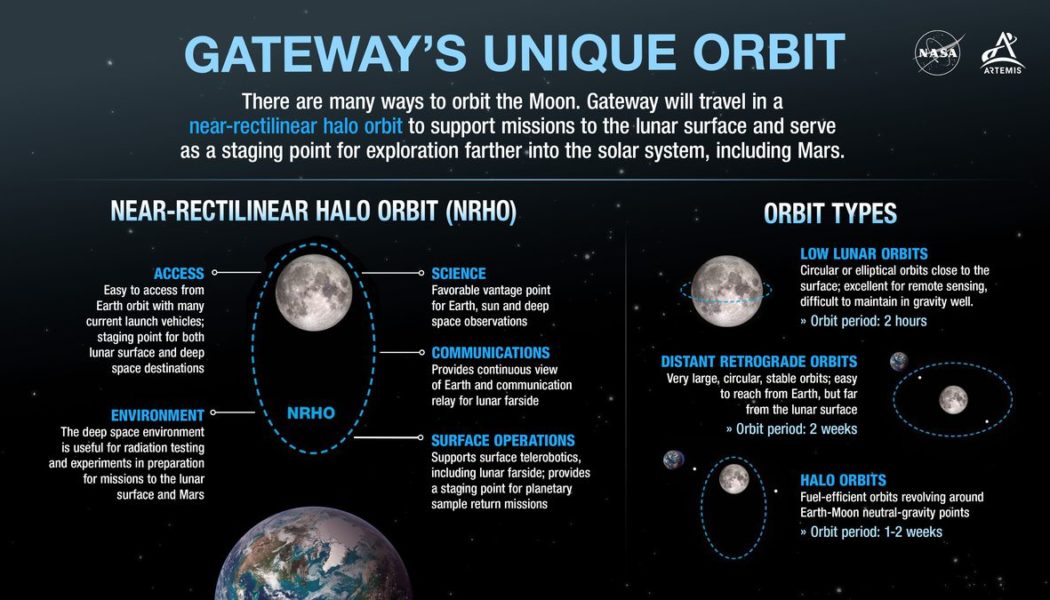

This distinctive orbit is called “near rectilinear halo orbit,” or NRHO for short. It’s a special seven-day path that spacecraft can take around the Moon, bringing vehicles relatively close to the lunar surface for one day before they swing out far from the Moon for the other six.

NASA is considering leveraging this orbit for its Artemis program — the agency’s effort to send the first woman and the first person of color to the surface of the Moon. Over the next decade, NASA wants to build a new space station around the Moon called the Gateway, a place that will serve as a training platform and living quarters for future astronauts headed to the lunar surface. And the space agency wants to park the Gateway on this loopy path around the Moon.

Since NASA hasn’t sent any spacecraft into this orbit before, the agency doesn’t have any experience with what it’s like to operate a vehicle there. This mission, called CAPSTONE, is meant to serve as a pathfinder. It can also be considered the first mission of the entire Artemis program, kicking off an intricately planned timeline that may culminate with people walking on the Moon again after more than half a century. “We view the CAPSTONE mission as a whole as a valuable precursor,” Nujoud Merancy, chief of the exploration mission planning office at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, said during a press conference.

When astronauts went to the Moon during Apollo, their path to the Moon was a more or less a straight shot on a massive rocket called the Saturn V. Once they arrived, they eventually put themselves into a relatively circular orbit around the Moon, one that brought them within 62 miles of the surface. That way, they could get down to the ground and back into lunar orbit relatively quickly.

This approach got them to the Moon fast but required a lot of resources. “One of the things that unfortunately you have to look at with respect to bringing spacecraft and equipment to the Moon using that typical approach is the significant amount of fuel that’s required,” Elwood Agasid, deputy program manager of the small spacecraft technology program at NASA’s Ames Research Center, tells The Verge.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23656327/nrho_infographic_may_2022.jpeg)

With Artemis, NASA wants to try some new approaches to lunar exploration. By parking the Gateway in NRHO, the future lunar space station will come within 1,000 miles of the South Pole of the Moon and swing out to 43,500 miles from the other pole each week. That close pass is a much larger distance than the Apollo astronauts had to cover to reach the ground. But NRHO provides other important benefits. Spacecraft in NRHO have a constant line of sight with Earth, allowing for continuous communication. That’s something that the Apollo astronauts didn’t have; when they were in lunar orbit, they passed on the far side of the Moon, blocking their signals with Earth for nearly an hour during each lap.

Perhaps the biggest advantage is that staying in NRHO doesn’t require as much fuel as it does to stay in a circular orbit around the Moon. That’s because this kind of path is known as a three-body orbit; spacecraft on this route are affected by the gravitational pull of the Earth, the Sun, and the Moon. As a result of this balancing act, this path is relatively stable for spacecraft to maintain, and they don’t need to expend much fuel to stay on track or to travel down to the surface.

“It has the net benefit of the low energy to get into and low energy to get out of,” Chris Baker, the program executive for NASA’s small spacecraft technology program, said during a press conference. Baker describes spacecraft in this orbit as “riding this balance point between the gravitational pull of the Earth and the gravitational pull of the Moon.”

Striking that balance is key, and NASA wants to verify when the Earth’s tug becomes greater on the orbit and when the Moon starts to step in. CAPSTONE will give the mission team real-time experience about what kind of maneuvers are needed and when fuel must be burned to properly keep a spacecraft on this path.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23656329/Screen_Shot_2022_06_28_at_4.44.21_AM.png)

With CAPSTONE, NASA is also going to test out a rather lengthy way of getting to the Moon. Since the vehicle is so small, it doesn’t have a lot of room for fuel, though it’s filled to the brim with what it could hold. “It’s a fairly dense package, mostly because the propulsion system takes up a lot of the mass, space, and volume of the spacecraft,” Agasid says. “It’s jam-packed. It’s a technological wonder.” The spacecraft also launched from New Zealand on a relatively tiny rocket called Electron, manufactured and operated by US aerospace company Rocket Lab. While Rocket Lab is providing extra thrust with an additional booster called Photon, it still doesn’t have a whole lot of fuel to burn compared to, say, a massive rocket like the Saturn V.

So over the next four months, CAPSTONE will get to the Moon through a route known as ballistic lunar transfer, or BLT. Using the gravitational effects of the Sun, CAPSTONE will loop out far from the Earth and Moon system, spiraling out farther and farther until it reaches the point it can insert itself into NRHO. It requires way less fuel to do but way more time to complete.

CAPSTONE is slated to reach NRHO on November 13th. Once in orbit, it’ll stay for at least six months, allowing NASA to capture critical data about this lunar path. The agency also plans to test out a new navigation capability, where the spacecraft will try to determine its own position and speed in space. That way, the vehicle requires less input from people on the ground, a capability that may prove to be useful for future interplanetary exploration.

When its mission is complete, NASA will send CAPSTONE on a crash course with the Moon, its historical job done. But for now, the mission team has to wait as the tiny satellite trucks along to lunar orbit. “The benefits of NRHO are clear, and we’re excited to see CAPSTONE test and validate this orbit for the first time,” Merancy said.