A Nigerian start-up takes on the problem of food spoilage at all steps of the production chain, one solar-powered cold room at a time.

OBINZE, Nigeria—

In the courtyard of Obinze Fruit & Vegetable market, haggling has peaked for the morning. Retailers, drawn from far-flung villages and suburbs of Imo state, southeast Nigeria and neighboring city of Port Harcourt, crowd the contours of the market hunting for bargains and fresh fruits. On a wood-framed table, under a trading booth made of stilts, rusty zinc, and leaky tarpaulin, dozens of vendors display lettuce, Chinese cabbage, purple cabbage, green beans, onions, cauliflower, strawberries, broccoli, and cauliflower.

Three women form a semicircle—their waists draped in multicolored Ankara fabric with tiny square patterns—in front of a half-dozen raffia baskets stacked with tomatoes, dripping with juice. In the soft soil, the juice leaves warped trails that become caked as the morning sun intensifies over the city’s 950,000 residents. Owerri’s strategic position and flashy hotels has helped it emerge as the region’s hospitality hotspot, attracting the affluent from the nearby commercial cities of Aba, Nnewi, and Onitsha as well as the oil city of Port Harcourt. However, thronging open-air green markets such as Obinze, key to feeding Owerri’s guests, still dominate the food economy.

Close to the exit gate at Obinze, a squad of loaders bring down sacks of cabbage from a semi-trailer in the open field. Thirty-two-year-old Muhammed Usman observes his stocks among the rising heaps. Before turning one of the sack’s over, he slashes the strings holding its rim together with a blade. The bruised cannonball cabbage that rolls out emits a strong and warm stench: its outer layers have become rotten, loose, and yellowish; no longer green and clutchy.

“Many have been damaged,” says Usman, as he lifts one of the cabbages. He speaks in hushed tones, but his apprentice picks up on the cue, takes out a pair of pen knives, and starts chopping, layer by layer. A pork farmer approaches, eyeing the heap of rotten cabbage.

“It’s now food for his pig,” says Usman.

Like the rest of the developing world, a large proportion of foods and fruits produced in Nigeria are lost before and after they reach the markets due to poor post harvest handling. Fruits and vegetables are particularly vulnerable. Experts estimate that farmers lose 3.5 trillion Naira (8.1 million Euros) per year to food spoilage. The loss is significant.

“Fruit-farming and trading is a high-risk venture,” says Usman, who was losing around 300,000 Naira (700 euros) worth of fruits and vegetables monthly before 2016.

Usman is hardly alone. Half a dozen farmers and fruit traders across visited markets and farm clusters recount various scales of their losses. Many have incurred heavy debts and losses that sent them out of business and farms.

As the losses festered, farmers and traders contemplated multiple remedies. Some settled for water sprinkling as a way of keeping the skin of the fruits fresh. But it was “midnight cooling” which became most popular. Overnight, leftover stocks were spread out on bare floors, rugs, mats, and tarpaulins at Obinze Fruit & Vegetable market and other outdoor markets. “This didn’t work out so well,” says Ibrahim Danladi, a fruit trader for six years.

Midnight cooling exposed the fruits to the moist night breeze, but the produce also attracted rodents, snakes, cockroaches and ants. Aside from feeding, poisoning and urinating on the fruits, these pests also defecate on them and burrow into the soft shells. As a result, the fruits and vegetables develop bad taste and odor, as well as discoloration and contamination. “There were a lot of complaints from customers,” says Danladi. “Many fruits perished, particularly green beans.”

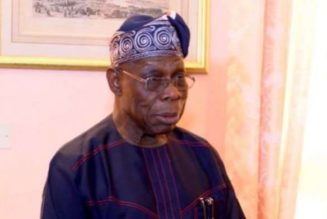

Twenty-five years ago, neither Usman nor Danladi knew Nnaemeka Ikegwuonu, Executive Director of The Smallholders Foundation, an NGO in Imo state focused on sustainable agricultural development for rural farmers. The world of smallholder farmers, particularly in rural communities, captivated Ikegwuonu, now the CEO and founder of ColdHubs.

In 2003, he established a community radio station, which he used to reach out to farmers with advice. He traveled from one community to another, learning farmers’ opinions, sharing their concerns, and listening to their stories. Each episode of his “bush radio” broadcasting discussed his findings. He believed tackling the problems he had witnessed in those markets and rural communities required unusual action. After obtaining his Master’s degree in Development and Cooperation at the Institute for Advanced Studies of the University of Pavia in Italy, with promising job offers from Europe in the pipeline, staying in Nigeria to pursue a career in clean-cooling in 2015 seemed an odd decision to some in his community. “Some felt I was running mad at that time. It didn’t make sense to my sister,” he recalls.

Ikegwuonu launched ColdHubs—solar-powered walk-in cold rooms—in 2015.

ColdHubs storage rooms extend the shelf life of fruits and vegetables to 21 days, up from around two days. The social enterprise operates on a ‘pay-as-you-store’ subscription model, where farmers or traders pay approximately 48 cents for each 20-kilogram (0.46 euros ) plastic crate of fruits and vegetables stored overnight. Its reusable plastic crates with built-in hands have perforated edges to improve ventilation. Meat and seafood cost $1.3 per night (1.2 euros).

Each storage cold room cabin has a three-ton capacity. The energy produced by its 120-mm insulating panels, which are mounted on the cold room’s roof, is stored in high-capacity batteries. These batteries, in turn, recharge an inverter, which powers the refrigeration unit.

ColdHubs now manages 54 cold-room facilities across the country, a 12-fold increase since 2018. ColdHubs says it has reached over 5,000 outdoor food market traders and created jobs. In 2021 alone, 2,390 431 crates of fruits and vegetables were stored in 54 company-run cold rooms as well as 18 cold rooms built for and managed by small and medium-sized enterprises over 3,655 days. Each crate holds up to 2o kilograms (50 pounds) of food (multiplied by the number of crates and days to obtain the figures for saved food). Ikegwuonu estimates that approximately 62,700 tons of fruits and vegetables were saved from spoiling in 2021. The increased shelf life enables farmers to make more profits from sales and resist panic and cheap sales. “It’s a great help at a reasonable price,” says Usman.

Ikegwuonu and his team knew from their days in radio broadcasting that getting the technology ready would be a struggle.

However, driving mass adoption, the lifeblood of ColdHubs, required even more delicate measures: Farmers had their own rigid ideas about fruit and vegetable storage, some of which were deeply rooted in culture and experience. Spiritual beliefs, linked to the goddess of fertility and fortune, makes farmers accept post-harvest losses as fate.

“There is already a culture in place,” says Terrence Isebe, ColdHub’s chief financial officer. “It takes a lot of effort and credibility to move them away from that culture. It takes a lot of convincing and practical evidence to win their hearts. It happens gradually.”

Farmers in northern Nigeria, for example, have long preferred sun-drying tomatoes, despite this practice posing a significant health risk. Farmers slice ripe tomatoes and spread them out in the sun or on a smoking hearth to dry after harvest. The dried carcasses are stacked and sold at markets in baskets, nylons, and sacks.

While ColdHubs set out to improve the longevity of fruits and vegetables, they soon discovered that consumers had a strong addiction to spoiled fruits and vegetables, or at least to their lower price. Spoiled fruits can be easier to sell than fresh ones. “It is usually much cheaper. But cheap is not the same as healthy,” says Augustine Okoruwa, a food technologist with the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN).

Okoruwa believes that thousands of Nigerians die each year from food poisoning linked to eating spoiled fruits, vegetables and other food, though more research is needed to establish definitive facts and figures. Around 420,000 people die each year from eating food spoiled by heat. “Our dream is to provide people with fresh, safe, hygienic, and nutritious food. Foods without discoloration. Foods without water loss. Food without the loss of taste. Food without wrinkles,” says Ikegwuonu.

As a result, the ColdHubs team made educating traders and farmers on post-harvest handling of fruits and vegetables, as well as food hygiene, a core part of their awareness programs. They staged practical scenarios to supplement seminars. ColdHubs stored fruits for free in some new locations for the first few days to demonstrate the efficacy of their remedies.

Users gradually began to leave positive reviews. In early July, Abdullahi Albert, a carrot and tomato farmer in Jos, in central Nigeria, requested additional cold rooms to meet the needs of the Farin Gada market there. “A single farmer can fill the existing cold room. More cold rooms are required,” says Albert, speaking by phone call. Similar appeals were made in Owerri’s Relief Market and Lagos’ Mile 12 Market. “We made certain that our solutions were unquestionable,” Ikegwuonu says.

ColdHubs isn’t Nigeria’s first foray into cooling stations. However, its model and success, according to Dr Muhammad Imran, a lecturer in Mechanical and Design Engineering at Aston University in England, remain unique: “ColdHubs offered a pathway and a model for commercializing cold storage.” Its reliance on solar power made it clean and sustainable, while also lowering its operating costs.

The lifewire of cooling is energy. Cooling services account for approximately 17% of global electricity consumption. Nigeria’s outdated power grids, which are prone to frequent outages, are barely enough to meet the country’s energy demands. This year alone, the country’s national grid, which generates less than 4,000 megawatts of electricity for its 200 million population, has collapsed six times. In comparison, New York, a city of about 20 million people, generates twice as much electricity as Nigeria.

By using solar-powered cool rooms instead of fossil fuels, ColdHubs estimates that it has avoided emitting 1,040,688 kilograms (2,294,324 pounds) of carbon dioxide. Tackling the cooling deficit with fossil-fuel-powered cooling technologies also generates more heat and accelerates the climate crisis. But as more fruits are kept from spoiling, emissions from methane—a powerful greenhouse gas emitted by burning fossil fuels, raising livestock, and landfill waste, but also by rotting fruits and foods—are reduced. Some studies estimate that food waste accounts for about 7% of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions.

Renewable energy projects in Nigeria, like those in many other developing countries, are underfunded.

Furthermore, ColdHubs addressed their solutions to smallholder farmers and small-to-medium scale traders. This group has been largely priced out of the expensive fossil-fuel-powered cool-storage systems. More than 80 percent of Nigeria’s farmers are smallholder farmers, largely restricted to rural communities where they lack access to storage technologies that can extend the shelf lives of their products. Only 8% of West African rural residents have access to electricity.

While many businesses want to emulate ColdHubs’ clean energy models, the road ahead is difficult. Renewable energy projects in Nigeria, like those in many other developing countries, are underfunded. Imran estimates that the start-up capital is at least ten times that of a fossil-fuel cooling station, which discourages “short-term and profit-driven” investors.

The state government is not encouraging innovations in sustainable and clean cooling. Importing key components for ColdHubs operations, for example, has been subject to high customs duties and delays. “The sector is neglected,” says Ogheneruona Diemuodeke, a renewable energy expert and lecturer at the University of Port Harcourt in Rivers State, Nigeria.

Reversing the trends, according to Diemuodeke, will require capacity building, intensive research, and increased funding support for clean-cooling initiatives such as ColdHubs. Businesses that emit few or no emissions should be rewarded with tax breaks, carbon credits, and additional funding from the government.

ColdHubs survived Nigeria’s difficult business terrain for seven years, during which many others have failed. It all started on July 30, 2015 , with what Ikeguono describes as a “funny looking” improvised cool room made of plywood, stilts, bolts, planks, and a window-unit air conditioner. Growth has transformed—and multiplied—that basic structure into a modern version. Each cold room is composed of 5-inch thick, insulated panels, a stainless steel floor, a safety door to keep cold air inside, and solar panels mounted on the roof to charge batteries that supply energy for night cooling.

A white-painted modular cool room now sits in the center of the open-field market in Owerri. In the interior, crates of fruit are stacked side-by-side with name tags. A stack of booklets lies on a one-legged table in the nearby container office, where customers’ names and records are kept. Traders come in from time to time to deposit or collect their fruits, fish, or vegetables as the sun and heat intensify.

In solving one problem, however, ColdHubs inflamed the appetites of farmers and traders, who then asked for more help in overcoming post-harvest losses in transit.

“A complete solution,” as Dike Chinedu, ColdHub’s head of supply chain and logistics, puts it, has to go back to the farm. “The sun heats up the fruits and even spoils them before you get to the market,” says Albert, a farmer of 27 years.

Chinedu observes that “so much time and life” is lost before fruits reach the market. Manual crop-harvesting, which is common in Nigeria, can take several hours to a few days. Refrigerated trucks for transporting farm produce are scarce and costly. Furthermore, flooded rivers and dams, rising mountains, and rutted roads inhibit access to thousands of food-producing communities and slow transit time.

When trucks break down on remote routes or in small towns, it can be difficult to find a mechanic on short notice. The nearest urban centers, where repairmen or auto parts are available, may be a long distance away. Mechanics are also wary of visiting those routes due to rising security threats and concerns.

Meanwhile, potholes pockmark transit routes. “The roads are dead,” says Zakriah. “There are times when I struggle for several hours to get past a bad spot.”

Seasonal traditional festivals and customs may mean that communities close their roads for a period of time. Truckers rarely protect produce from heavy rains, harsh sunlight, heat, and dust.

In mid-July 2022, ColdHubs launched two solar-powered refrigerated trucks. The trucks would pick fruits and vegetables directly from farms and deliver them to markets. “It is a moveable cold room,” says Emmanuel Monday, Coldhub’s chief technology officer. “With the trucks, fruits can retain their freshness from the farm to the family table.”

The new trucks are better suited for packaging, which was a major shortfall in the existing transport system. Conventional trucks depend on tarpaulin to protect the fruit, which is tightly packed in bags and raffia baskets inside the truck, with no room for ventilation, and often exposed to rain, heat and sunlight.

Tomatoes, carrots, and green peppers are stacked in hand-woven baskets made of palm frond fibers. These fibers’ edges are typically spiky. In transit, the soft shell of the produce bruises against the sharp edges of the basket as the vehicle staggers through potholes. As a result, the fruits get cuts and blisters and discolor. In some cases, the fruits packed at the bottom of the trucks are crushed by the weight of those above.

The new ten-ton ColdHubs trucks’ design aims to resolve these issues. The trucks’ frames are strengthened with extra fasteners, bolts, and grippers to keep them stable driving around potholes. The produce is kept in plastic crates vertically stacked and string-strapped from bottom to top: the weight of the fruit on top will not rest on those below.

As soon as the trucks arrived, the vendors at the Farin Gada fruit market in the northern city of Jos burst into raucous celebration. “We were happy to set our eyes on that truck,” says Albert, the carrot and tomato farmer. “We need more of those kinds of trucks.” In Nigeria, food produced in the north is often sent directly to cities in the south, where the middle class pays a higher price.

Meanwhile, more ideas are being developed. ColdHubs will soon begin construction on a new set of cool rooms aimed at farm clusters in hard-to-reach communities. Farmers will then be able to deposit their harvests directly from their farms while waiting for pick-up trucks. “We want to secure every stage of the value chain,” Ikeguono explains.

While these other achievements are admirable, ColdHub’s ultimate goal is to alleviate food insecurity and poverty by increasing the returns farmers and food vendors get from their produce. Post-harvest losses recycle poverty. Last year, Mishack Adamu, a tomato and green pepper farmer in Kano, northern Nigeria, lost more than half of his crop to heat. “I’ve been deeply in debt,” Adamu says.

As farmers like Adamu continue to suffer from these losses, the widespread effect of food scarcity unsettles all of Nigeria. More post-harvest losses, according to Terrence, means less food available for households. Food scarcity, in turn, drives up prices, decreasing household purchasing power. Some researchers claim that the price of food has climbed by more than 100% just in the last few years.

Nigeria, a major food provider to West Africa, is finding it harder and harder to feed its people. The World Food Programme said that in 2021, seven out of 10 Nigerians did not have enough to eat, placing the country at the risk of acute food insecurity. “Every morning, there are 200 million mouths to feed in this country,” Ikeguono says, gently stroking his dense and dark beard, sprinkled with sparse gray strands.

Back in Owerri, at the Coldhubs headquarters, Ikeguono muses on the company’s future. A mural of green and white hues is painted on the wall behind him. A densely leafed star apple tree flutters outside the bungalow office.

When he got the idea for this business six years ago, there were only a few friends to cheer him on, some of whom worked as amateur laborers to help out. Ikeguono‘s ambitions and challenges have shifted as he now operates in 22 states with over four dozen employees.

Now, he wants to provide at least a 100-ton storage cold room to each of Nigeria’s 36 states, up from the current 3-6 tons. He has also begun negotiations with the government to build a solar-powered “all fruit and vegetable market.” The existing markets didn’t include cold room spaces in their takeoff layouts.

Securing land for this expansion could be a nightmare. “It is one of our biggest difficulties,” says Terrence. Available spaces are becoming increasingly competitive and costly. Getting land in Lagos, Nigeria’s most populous city, took three years of concerted effort. There are also many other markets where negotiations for land and space have stalled, especially in the country’s south.

“We want to solve these problems profitably,” says Ikeguono. “We do not want to constitute an extra burden on an already overstretched population. In all this, we have to keep our integrity and honor.”

Any sustainable food game-changers on your radar? Nominate them for the Food Planet Prize.

Tagged: food