Alisa Weilerstein’s latest project is a series of staged solo recitals that weave Bach’s cello suites with newly commissioned works.

When the cellist Alisa Weilerstein found herself cooped up with her family at the start of the pandemic, her first instinct, like that of so many classical musicians, was to find some way — any way — to communicate.

She joined the artists who found solace on social media, streaming a movement of Bach’s cello suites each day, for 36 days in a row. “I just want to have a kind of outpouring of music, of thoughts, and everything else,” she told The New York Times then. “Right now all I really want to do is give.”

It didn’t last. Come that November, Weilerstein had put her cello away, and she was taking long walks on the beaches near her home in San Diego instead of practicing. When she finally forced herself to play again, she found herself staring out of the window, wondering what her field might look like when, or if, performers returned to the stage.

“To everyone’s credit, I think, everyone is wrestling with this issue,” Weilerstein said in a recent interview from Toronto. “We all had a lot of time to think about what it means to really connect with an audience, what it means to connect with each other, and an appreciation for being in one communal space.”

If Weilerstein’s response was a common one to a common crisis, the result of her reflections shines with uncommon ambition, so much so that it is hard to think of many soloists of a similar stature who would dare to bring anything like it to the stage.

Meet “Fragments,” a project whose first installment — of six — Weilerstein will perform at Zankel Hall on April 1. Certain aspects of it may be familiar. She will be there, playing solo. She will perform a Bach suite in its entirety, and she will play it with her typical, heartfelt passion. She will offer new music: quite a lot of it, selected from works by 27 composers she has commissioned.

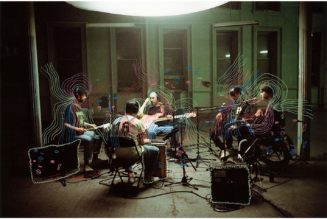

But this project is intended to reimagine what a cello recital can be, to challenge some of the conventions that Weilerstein thinks might inhibit a listener’s immediate response to the music, and to add layers of theatricality to the arguably staid traditions of the concert hall, in an acceptance that a musician is, after all, performing on a stage.

So each of the six programs, which Weilerstein will offer over the next few seasons, will have a dramaturgical element: Hanako Yamaguchi, the former, longtime director of music programming at Lincoln Center, is her artistic adviser, and her production team includes the director Elkhanah Pulitzer, the set and lighting designer Seth Reiser, and the costumer Carlos J. Soto. There will be limited program notes in advance, little to guide listeners except their ears and eyes through a collagelike narrative arc assembled from musical fragments.

“There’s a lot of things that classical music does uniquely well, and it’s important to preserve those things,” Weilerstein said. “I do think, though, that we clearly have a problem, that we are not connecting with enough people, and that we are relying too much on our old models of presenting, especially when it comes to new music.”

AT FIRST GLANCE, “Fragments” might appear to be another of Weilerstein’s explorations of Bach, a successor to her all-in-one-night performances of the six suites, her emotive recording of them on the Pentatone label and her pandemic streaming series. But Weilerstein thinks of it not as “a new approach to Bach,” she said, rather “a celebration of the really disparate voices in contemporary classical music,” with Bach as a common reference point.

So “Fragments” is not, thankfully, another addition to the increasingly passé genre of “response” programming, in which composers are commissioned to write works on the dispiriting condition that they must speak to a piece by the masters of the past. Having scoured the internet to survey the new-music scene, and consulted with past collaborators including Osvaldo Golijov and Matthias Pintscher, Weilerstein invited 28 composers to participate. The 27 who agreed — including Tania León, Joan Tower, Carlos Simon and Daniel Kidane — make up a roster that is remarkably diverse demographically and stylistically, but almost all of them asked if they should write with specific reference to Bach, Weilerstein recalled. She left the choice up to them.

“Some did,” she said, “and some very much did not.”

Caroline Shaw, whose “Microfictions” for Weilerstein is the second volume in a run of collected miniatures that she has also written for the Miró Quartet and the New York Philharmonic, said that her piece is not an explicit response to Bach, but that his influence was surely present in it.

“I live with his music all the time, I love it deeply,” Shaw said, adding that the second book of “The Well-Tempered Clavier” has been her “soundtrack” for the past year. “It’s very hard to write anything for solo cello and not have some subconscious relationship to Bach.”

Weilerstein did set some rules. She asked that the new pieces be about 10 minutes long, and that they come in two or three fragments that she could intersperse with other scores without violating the meaning of the music. Bach was not available for consultation, but she is subjecting his suites to the same treatment.

“There was a temptation to write something really virtuosic, really out there, really avant-garde,” said Reinaldo Moya, one of the more junior composers in Weilerstein’s group, “because you’re not going to have the chance to work with a soloist of that caliber every time. At least I don’t.”

Free to write what he wanted, Moya drew on the personal ties that he has to Weilerstein through the conductor Rafael Payare, her husband. Earlier in their careers, Moya and Payare both played in the Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela, a country that has such an addiction to caffeine that it has a precise linguistic taxonomy for coffee and its functions. Moya’s fragments depict an early-morning brew, an after-lunch pick-me-up and a sludgy cup needed for staying up late.

“It felt a little bit — all right, it felt a lot risky to give her a piece about coffee like that,” Moya said. “But I wanted to go with my gut, and relate my work to something that might connect with her on that level, not a technical or a composer-y level.”

WEILERSTEIN HAS NEVER had the reputation of being a new-music specialist, but she has given her fair share of premieres, and few of her colleagues on the international circuit can list anything so bold as her recording of Elliott Carter’s Cello Concerto on their discographies. She has evidently thought hard about how contemporary composers can be given a fairer chance to break through to audiences, especially to those people for whom contemporary art, say, is an easier ask.

“There are myriad reasons, of course,” Weilerstein said, exploring the apparent divergence in the fields, “but there is one very fundamental thing, which is, you walk into an exhibition, you see the painting or you see the work of art before anything, and it can hit you right where it needs to hit — and then you can find out all the context around it. With contemporary music, there’s so much context put around it even before we’ve heard anything.”

For that reason, the lack of program notes — before the lights go dark, the audience will be given only the most basic information about the project, and the names of the composers they will hear — is a core part of “Fragments,” and a sign, its creators said, that, for all the deliberate, thoughtful artifice, the focus is on the music.

“To shed the Rorschach inclination towards finding meaning in the program before hearing the music was a really important piece of the puzzle,” Pulitzer said. “How many of us do that, where we look at the bio, we’re making assumptions about gender, race, nationality, compositional precedent, who where their teachers, and when were they born?”

The aim, she added, is to strip as much of that presumptive meaning as possible away, so that listeners can follow Weilerstein’s attempts to create new meaning in her musical quilts, and “dare to embark on this journey of not knowing, and allow it to be OK.”

For Shaw, that was part of the attraction of “Fragments,” beyond the obvious appeal of writing for a soloist whose visible commitment expresses such a clear love of music.

“Going to hear a concert and not looking at what’s on the program and not knowing what comes next — those have been some of my deepest and most revealing listening experiences,” Shaw said. “There’s also something beautiful and important about presenting different composers side by side, and behind a curtain, so that you’re not focusing on their name, or whether or not they’re Bach.”

The staging does offer some hints about the music, as if to hold the listener’s hand. Reiser’s set stays constant, a deconstructed theater arrayed so that it evokes soloists’ constant struggles to create “a room of one’s own” as they travel the world’s halls, Pulitzer said, and at the same time “reawakens the spaces for the people who are familiar with them.” Each composer has a specific lighting color, to give a sense of which fragments combine to make wholes.

There may be people, Weilerstein admits, who are put off by even a modest staging, or by her tinkering with performance traditions. For her though, “Fragments” is an attempt to make the concert hall more of a place of adventure again, and less of a dead end.

“It’s like the E.M. Forster phrase, ‘only connect,’” Weilerstein explained. “This is the philosophy behind the project, fundamentally: connecting the pieces, connecting the voices of our time together, connecting the familiar and the new, connecting this music with the audience without the barrier of so much contextualization, categorization, bias, all of these things.”

“And connecting,” she added, “our contemporary world with the concert format. This is what it’s about for me.”