This article originally appeared in the September 1994 issue of SPIN.

From billboard to shining billboard, Kate Moss’s lank frame and doe-eyed stare have dropped a volatile mixture of fame and fury into her 20-year-old lap. Elizabeth Mitchell hops continents to sift through the myths and mystique.

If Kate Moss were to open her ripe, Cupid’s-bow mouth to make a public statement, it would go something like this: “I’m not anorexic, I’m not a heroin addict, I’m not pregnant – all the shit they fucking say about me is not true. It’s a load of lies the media made.” Moss pauses for breath.

She is a lot of life when you meet her outside a picture.

Moss is not making a statement. She’s enduring an interview, a process she hates because she doesn’t want to give any more of herself away. This is the girl who was stripped of makeup and clothes, and pinned up everywhere; who appeared in such profusion throughout the pages of Harper’s Bazaar that it seemed like a family album; who, preserved by Calvin Klein in the silence of photographs, has waited with us for buses, has lingered against the walls of buildings, gazed out from Times Square – the kind of repetition of image that world leaders as savvy as Marshal Tito have employed to hold the savage, furious fragments of their nations together, and which, in our country, sells perfume and underpants.

Moss, known for her sultry or sulky silences, speaks in tongues – over a chirpy base of British half-cockney teen drawl, she liberally scatters upper-class intonations, yelps, giggles, glottal stops, mock tear-stained pleas, and wicked cackles. She hits key phrases in regular rhythm: “at the end of the day,” “oh my God,” “whatever.” A typical response goes something like this: The most embarrassing moment of life was “when I did the Isaac Mizrahi show in L.A.” – declared decisively – “Johnny was there” – referring to her boyfriend of the last six months, 31-year-old actor Johnny Depp – “and it was the first time he’d ever seen a show. I was like, “Pleeease don’t come.” The show itself was the most ridiculous I’ve ever done because it was this fan-ta-stic, faaabulous, dada-daaaa,” she trills, throwing her hand over her head in Ziegfield style, “No,” she backtracks, smoothing potentially ruffled business feathers, “it was fun, but it was just knowing he was out there, and I cared what he thought about my job.”

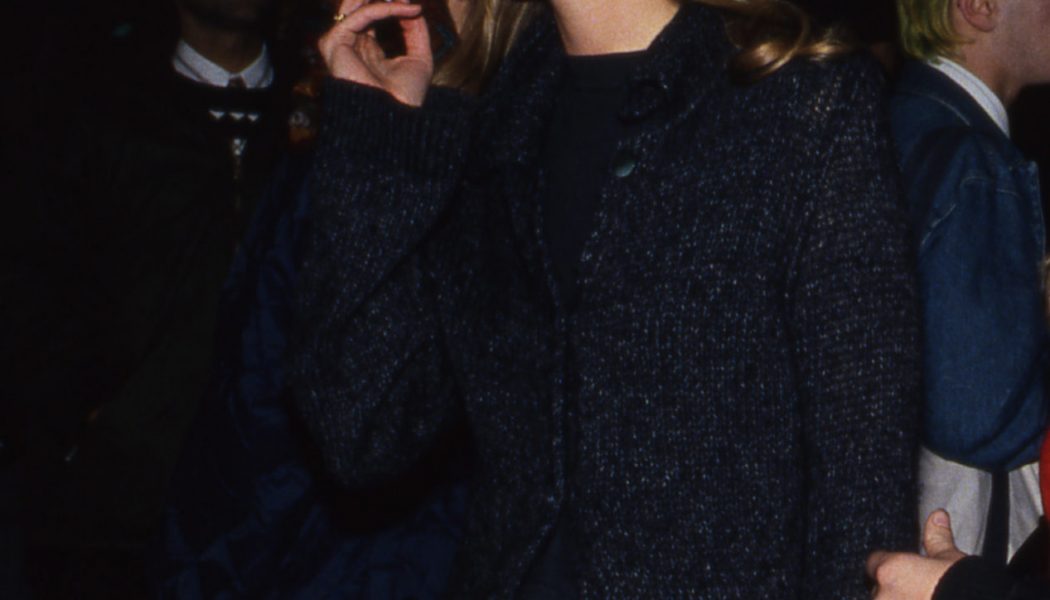

Moss, at five feet seven inches and now all of 20 years old, sits across from me perched on one curled leg, on the patio of a hotel bar in Rome. Don’t set your clock by a model. I have flown to this city and waited patiently for three days in my room while Moss, in a closed shoot, angled her way across paving stones in stilettos for yet another picture, on days that began at 5:30 A.M. and stretched on until 9:00 P.M. “I looked like a freak,” says Moss. “I had this long wig on and shit. It looks fine in the pictures, but in real life, I looked like a real prick.”

Tonight, Moss’s hair is pulled back in a bun; she wears a black camisole and, whether achieved by biology or bottle, a glow of health. Around her neck is the one marking of celebrity-a narrow strand of diamonds bestowed on her by Depp. She is thin, but not the skeleton heralded by editorials. A small black heart tattoo is etched on her left hand. I admit, this woman who has become the Other Woman for millions of Americans worn out by extreme beauty images has quickly charmed me -launching into relaxed banter the moment she is dropped off, with a big screen kiss, by Depp. Sitting across from her, I recognize the comments I’ve heard from detractors-“she’s not even pretty”-as patently absurd, the brand of nihilism out allows young boys to kill small animals.

Moss is the first supermodel in many moons who doesn’t look like Superwoman. She’s the beautiful slacker icon, who almost single-handedly shifted body image from ripe, pumped-up flesh to an attenuated preteen slump. In a society where women must keep an anxious and wary eye on the health of their rights, the repetition of her image prompted the question: is Kate Moss good for women? A picture of Moss only depicts a carefree girl from Croydon to herself, family, and friends. To the rest of the world it’s a mirror, a metaphor, an attack.

“She’s a vision of the poetic quality of women that no man can ever interpret,” says feminist critic Camille Paglia, noting the deficiencies of drag. “Girls are in crisis, because they are being preached to by the feminist establishment: ‘The most important people in the world have ataché cases. You must become like us,’” continues Paglia, who believes the new feminist ideologues have denigrated the valuable pursuit of love and beauty. “My whole generation was all about finding the truth about life without social status and money. What Kate Moss represents to me is a rebellion of the young women against that other talk.

Moss’s life began where her parents’ did, in Croydon, one of the largest boroughs of London, on January 16, 1974. Two years after her arrival, mother Linda, a bartender, and father Peter, a travel agent, would provide their feisty daughter with a perpetual sparring partner. “For a second, I was into one doll. But not for long,” says Moss. “I was more into fighting with my brother, Nick, not really playing. I used to pin him down and spit in his face. I was disgusting.”

Out in public, the Moss’s unusually pretty little girl was shy. She would attend ballet classes with her cousins, but refuse to perform in front of an audience. Yet at home, where she directed backyard shows employing the other children, her sleep was filled with dreamscapes of fire.

Moss and her brother attended a rough public school, while their relatives went to private. Moss promptly learned the rules of fitting in. “I was a sprinter and goal attack in net ball, up until I started smoking—until I started being naughty. I started to get my period every week it seemed, anything to get out of any physical activity. It was just not cool in school to do gym.”

At home, tension built as the Moss’s marriage hit rocky ground, and Kate would escape from her room, with its pictures of Matt Dillon and its perpetual warble of Blondie, to carouse with friends. She was one of the most popular girls, with a regular round of older boyfriends. “Everyone used to go down to this park in Purley,” remembers Moss, “and just drink cider and get off with each other behind the bushes.”

“We had a punk thing going on for a minute,” she recalls. “When I was about 10, me and my friend went up to the park in T-shirts and my mom’s stilettos and green lipstick and my hair back-brushed. And we got sent home from school.”

Like other Croydon females, Moss’s training behind the shop counter started early. First there was a brief stint in the toy store of her best friend’s father on Saturdays during high school—”It made me crazy. I had to count rubber spiders and stuff.” Then she moved on to a men’s shop. “I went on carnival because I got paid 10 pounds more. So I called in sick. And then my boss saw me on the carnival flat having a laugh, so he sacked me.”

With the Moss marriage in trouble, Kate was left to her own devices. “Literally, my parents would let us do what we wanted. I was smoking when I was 13 in front of my parents, and drinking. I’d have parties where I’d come in at 3:00 in the morning because somebody chucked me out then. It actually worked out to my benefit, because you end up thinking for yourself because you know you’re not rebelling against anything.”

Moss’s parents split when she was 13, and, torn by the decision, she stayed with her mother, whom she considers her mentor, while her brother moved in with her father. “We’ve never really spoken about the difficult times,” says Peter Moss, described by his daughter as unflappable—”the most chilled out person ever.” “It’s a shame,” he says, “but it’s not always easy. I suppose as they get older, the time might come when they feel happy to talk about it.

“We used to go to more exotic places on vacation,” says Moss, recalling the perks of her father’s job, “but then when my mom and dad split up, it was Florida. Every year. That’s it. Sun. Beach. Orlando. Shut the kids up.”

“What was your first impression of the U.S.?”

“Everyone wore stone-washed jeans and [Adidas] trainers.”

“And then you picked up on those sneakers.”

“Yeah, well, a few years later, thank God.”

Moss’ parents divorced when she was 14, and it was that year that the tentacles of fate found the bedraggled “dosser” waiting for a London connection from JFK airport with her brother and father after three arduous days of stand-by. Moss was obsessed exclusively with the destiny that would land her a place on the last flight out. She was smoking, perhaps dreaming of the boy she was leaving behind in the Bahamas who had just initiated her into sex, keeping on a bored watch on the screaming matches taking place at the ticket counter and shaking of the remembrance of the rat under her airport counter that morning when—bang!

Sarah Doukas, managing director of the Storm modeling agency in London, spotted young Moss across the terminal. Doukas had been touring America with her brother, looking for potential models and was exhausted from the layover. “I had just said to my brother, ‘If I never see another girl, it won’t be too soon.’” But Moss was different. “Fresh, beautiful, great bones…” On the airplane, they approached her.

Internally, Moss’ first reaction: “All right…you freak.”

A year later, Moss was topless in the Face. And true to the scare stories of the modeling industry, she found herself one of the plaintiffs in a sexual harassment suit against a “dodgy” London lingiere photographer who was later found guilty. But for a young girl from modest Croydon, with little interest in academic pursuits, the opportunity to model was obviously the ticket upward and out. “Teachers told me, ‘Do that, try and make it,’ because so many of my friends that went on to college dropped out. Most of my friends were suspended or expelled for smoking pot, having fights, calling the teacher ‘bitch,’ just causing trouble basically. They didn’t even make it to the end of school.”

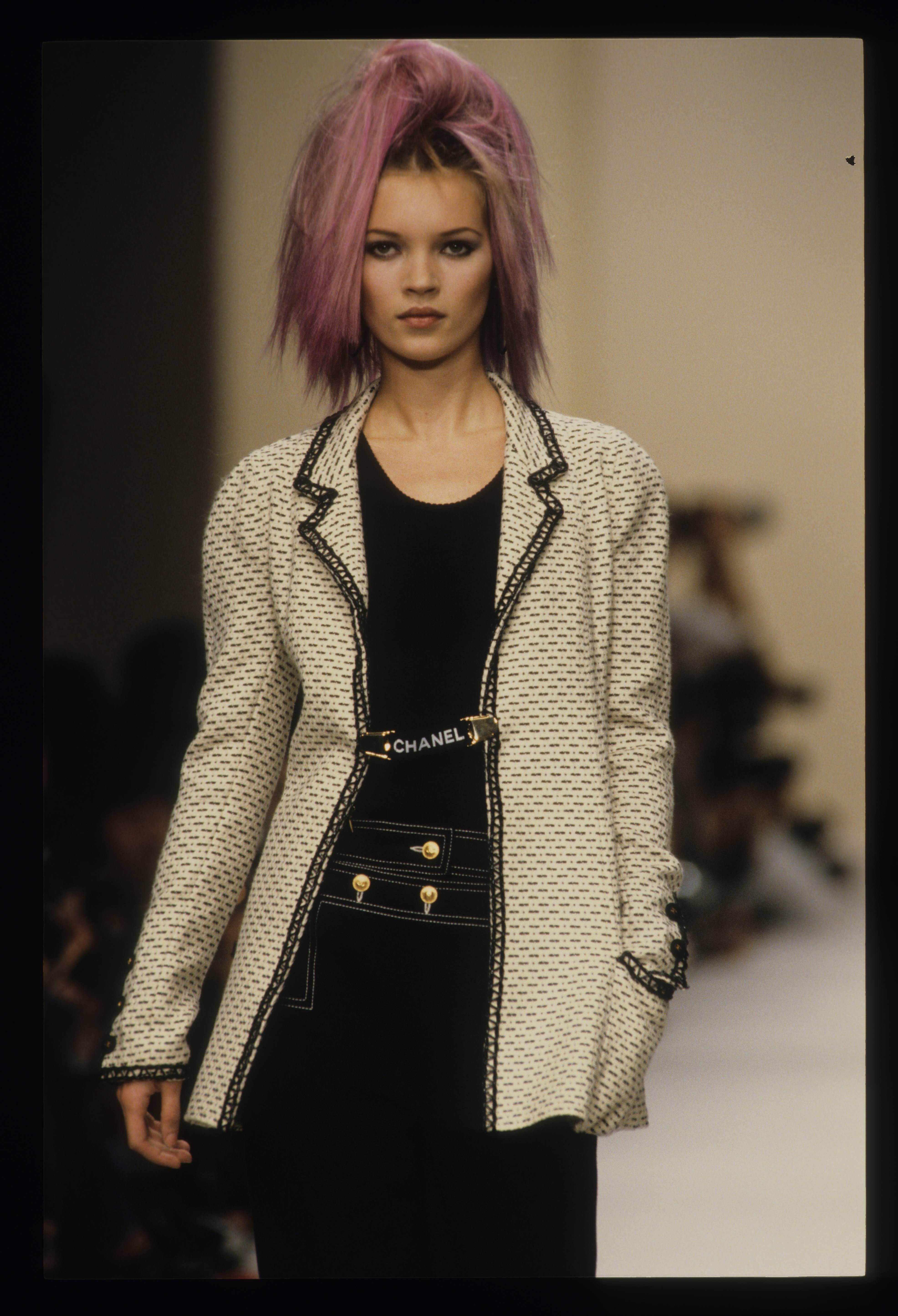

Fabien Baron, the creative director of Harper’s Bazaar, had been looking for the anonymous girl with the quirky smile he had spotted in a picture at a Barcelona fashion photography festival. Then one day, Moss walked through his office doors. Calvin Klein had been searching for the next girl to kick off his campaigns. “We bring the girl to Calvin, and poom,” remembers Baron. Moss inked her three-year, six-figure contract with Klein, and the rest, as they say, is her story.

“If I didn’t get discovered,” says Moss, “I’d be working in a bar like my Mom.”

Almost 30 years after Twiggy hit the pages of Vogue, Kate Moss found herself at the center of body image controversy. The issue had strictly been personal before, but now, indisputably political. “I always used to get teased for being so thin. I used to wear these boots and they used to call me Stick in Boots and shit—you know, like Puss in Boots? I wasn’t really insecure about that. It was just wankers.”

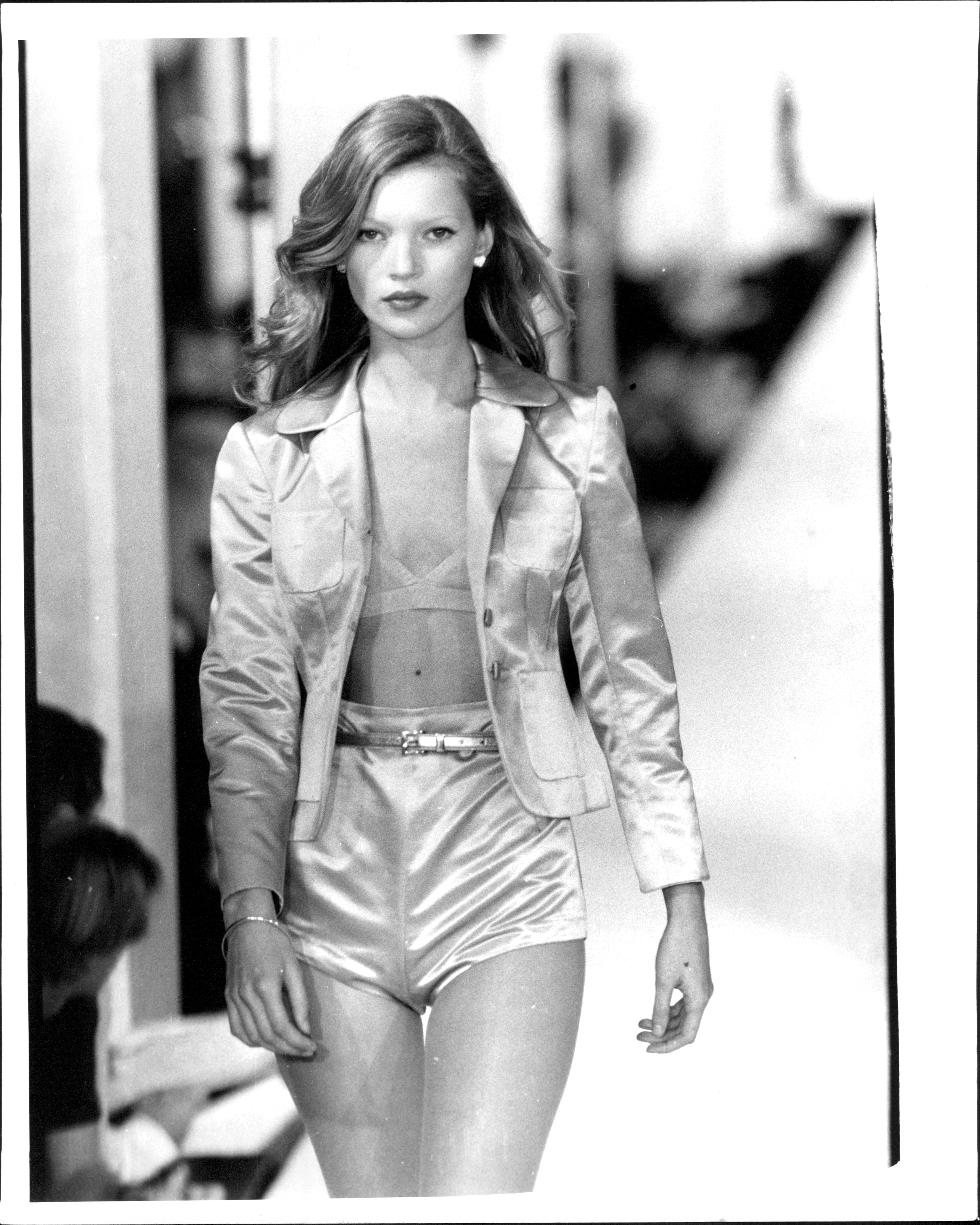

The shot heard round the fashion world were the pictures of the nubile Moss in underwear in British Vogue—one of their best-selling issues ever. “No pedophile would pick up that magazine,” says Doukas, “but I’m sure they did after the press hype.” Then came the Calvin campaign.

Eating disorders predate fashion magazines—with the first documented cases of the former in England in 1684, and the wide distribution of the latter in the late 1800s. But few observers would question the negative psychological effect that redundant images of female beauty have had on women: In the U.S., one-third of all females reportedly are unhappy with their bodies, eight million are enrolled in Weight Watchers, and an estimated one million cases of anorexia each year make the U.S. the most afflicted nation.

“Did you ever go through a phase of being anorexic?” I ask Moss.

“No,” she says vehemently. “Not at all. I’ve never thought about eating or weight. It was kind of boring to me to have to eat. I would know that I had to, and I would. When that stuff was brought up, I couldn’t believe that people were actually thinking that I’ve got this—it’s a serious thing. And people were accusing me of encouraging it, and that was really disturbing. People that know me, know that I’m fine, but it’s like a planted seed in their heads, and if I go out to dinner, and I’ve already eaten, people are like, ‘Look at her,’” she whispers.

While her brother, Nick, got into a fistfight with a guy slinging anorexia slurs in London, the media went wild, running stories about the “dangerous message being sent to weight-obsessed teens” and publishing pictures of a dead-eyed urchin with Marlboro Lights and vodka tonics in hand. The Houston-based Federal Wage and Labor Law Institute was inundated with calls when Esquire magazine printed the consulting firm’s telephone number, interpreted as 1-800-SOS-WAIF, asking for donations of “warm miso soup and tuna carpaccio” to feed the scrawny models.

“Kate’s just been a scapegoat of a fashion trend,” argues Baron, who considers Moss’s early photos an important step forward in fashion photography. “It’s not fair to her. She’s a totally normal person, totally natural, unlike most of the models of the ‘80s that were into silicone, doing injections for their mouth, changing the color of their hair, and burning everything. Nobody cared about that.”

Camille Paglia agrees. She’s a fan of the pagan porn of the Obsession for Men campaign displaying Moss’s naked supine body on a black couch. Paglia, in fact, considers it too hot to serve as urban wallpaper. “If you were to say, ‘What were the ‘90s like in America?’ that has to be one of the great images, because it encapsulates the search for femininity, and the new homoeroticism. That image, going by on the bus, is one of the great examples that everyday America has turned into Babylon.”

That sort of observation would likely infuriate Ann Simonton, a former model turned whistleblower, who founded MediaWatch in Santa Cruz 10 years ago. “We encourage our readers to deface a billboard. We like the graffiti that says ‘Feed Me,’” she says, referring to the riot-grrl scrawl which began appearing on public images of Moss’s skinny, bikini-clad body last year.

Simonton guards against all varieties of “public humiliation against women,” and is planning a boycott of Calvin Klein and a postcard campaign. “The cards feature an image of Moss that looks like she’s been busted in the lip, where she has her hand over her mouth and looks hurt. We are particularly opposed to images of women who are both nude and look hurt.”

Ironically, this image of Moss bereft of makeup, shot by her ex-boyfriend for the Obsession for Women campaign, is her personal favorite of all the professional photos taken. “It looks most like me to me,” says Moss.

Cultural critic and African-American feminist bell hooks, who claims to have had “throwdown” debates about Moss, considers this paradox: “The question is: How do we shoot images of women in a patriarchal culture, where we are vulnerable, and those images not be interpreted as the moment of potential victimhood? ‘Oh, because you’re looking cute and vulnerable at this moment, I’ll rape you.’”

Earlier, Moss told me: “I’m not a feminist, so when I do something, it’s what I think is fine. And then somebody says, ‘Oh, the feminists are going crazy.’ I think: ‘My god, maybe I’m not sticking up for women.’ And that’s kind of scary.”

Over the past year, Dr. Andrew P. Ordon, assistant professor of plastic surgery at the University of Connecticut and owner of a New York private practice, has greeted more than 100 patients, some bearing images of Moss, all in search of the “hollowed-out” look. “She is the true poster child of ectomorphs,” says Ordon. He confesses the limits of the operation, “We’re not making waifs out of people. We are making them more waifish.”

His skill at this $3,000 removal of cheek fat—dubbed by his assistant “the waif-face procedure,” or “the Kate Moss procedure”—has earned him live television demonstrations. Says Ordon, “Someone trying to achieve this look may go to extremes with eating disorders, and this is why this procedure is good for the 110-pound model who says, ‘To get the look I want, I’d have to go down to 90 pounds.’”

Of the 5,000 people who each year resort to removing their intestines to help them lose weight, 80 percent are women. In 1992 alone, 1,000 of America’s plastic surgeons reduced, increased, reconstructed, in addition to removing implants in the breasts of some 130,000 women.

I ask Moss what she would change about herself.

“I’d like to be an inch taller.”

“Would you really?”

“Yeah.”

“What would it do?”

“I don’t know,” she says, laughing. No, just between my ankle and my knee—just an inch, it’s weird,” she says, embarrassed and amused by her confession. “I’m quite happy with myself, otherwise.” She begins to say something else, but stops quickly, as if suddenly shy. I prod her, and she reluctantly offers up her other desire. “I never felt this way before, but now I would like more stimulation, as in education,” she says. “Before I felt, ‘I know things.’ But now I want to read and take in a lot more than I ever did before.”

On the dreamy shores of a Caribbean island, siphoned of color, Kate Moss surges forward with the waves, and falls back, adjusts her bikini top, blinks away saltwater. And then comes the narcoticized, mumbled pitch for this TV perfume commercial: “I love her. I love you, Kate. Love is a word you can’t explain. Love, it was so beautiful, like, like paradise.”

The viewer does not just want to smell like Kate.

Moss pauses to assess that campaign, photographed and, in a surprise move, overdubbed by her ex-boyfriend Sorrenti. “That was really weird,” she confides, “because we split up soon after that. I would be sitting at home late at night on the phone with the TV on, and I’d be like, ‘Oops.’”

It seems all Moss’s romances are public ones. She and Depp have kept gossip columnists frothing since their first encounter at New York’s hip bistro Café Tabac in January. Was it love at first sight? “No, not from the first moment I saw him,” says Moss. “I knew from the first moment we talked that we were going to be together. I’ve never had that before. He’s sweet,” she says laughing. “He is, he is, he is.” She recently rewarded his amiability with a 31st-birthday gift of a platinum rattle ring filled with black pearls.

Then there are the rumors: Is she pregnant?

“I’m not pregnant. I’ve got this photoshoot in St. Bart’s and the editor said to me, ‘Kate try and put on ten pounds. Go on. I want to kill the waif, kill this anorexia shit.’ So I ate, ate, ate. I was in Paris and I was happy and I was with Johnny. All of a sudden, they were saying in London that I was nine stone [126 pounds].”

Then there were the tales of their Las Vegas marriage in May. “There was something in

the National Enquirer that said I wrote my name Kate Depp or something. I just laughed hysterically. The next thing you know, we’re getting married.”

How does she feel about Johnny’s “Winona Forever” tattoo? She looks embarrassed. “It doesn’t say Winona anymore. He had it deleted. Delete, delete, delete. Whatever.” The tattoo now allegedly propels “Wino” into eternity.

“What’s the best advice your mother ever gave you?” I ask.

“To not let men treat you like shit,” Moss says. “Ever since she said that to me, it’s worked.”

Earlier, on the day I sat across from the lovebirds on a flight to Rome, hearing now and then over the engine the soft, resonant kiss kiss kiss of two celebrities in love, Moss had reportedly engaged in a high noon knock-down, drag-out catfight over Depp with another model at the Royalton Hotel in New York. Her New York agency, Women, and several gossip columnists agree with Moss’s statement: “It’s absolute rubbish. I met him in the airport that day. This is horrible. Why do people do that? It’s so spiteful.” Indeed, almost all of Moss’s press is in such contrast to her apparent personality, one is reminded that a silent woman is the most amenable canvas for other people’s projections—including advertisers.

“She’s not selfish. She’s got a good sense of humor,” says Nick Moss, now also a model and the pimp in the new Rolling Stones video, grudgingly assessing his older sister. “When she’s bitchy, she’s very bitchy. That’s always been in her blood.”

Throughout the industry and with her loyal and longtime friends, Moss is known for being sweet and hardworking, with her worst trait merely indecision. “She’s very smart,” says model Naomi Campbell, who shares with Moss and Christy Turlington the nickname “wagon,” the Irish term for drunk. “People have this image of her as a little girl and it’s completely crap. If she were, she wouldn’t be where she is.”

Indeed, Moss says she feels strongest when she’s taking control of her career. “It’s a good job to have because in this industry we’re quite powerful as figures,” she says. “The public doesn’t see the whole picture.” But every shoot doesn’t play out like a NOW meeting. “I have this mole on my breast,” she says quietly, “and photographers would be like, ‘If you’re not showing your breasts, then we’re not going to use you for this job.’ This was a woman saying this, a friend. I was shy at 15, and I didn’t want to show my tits. She got her way. Because then there’s the makeup artist, the makeup artist, the stylist, the hairdresser—everyone’s like, ‘Get over it. You’re a model. You’re supposed to be able to show your pussy.’”

“What do you think about when you’re posing?” I ask.

“When I’m going to get home.”

Moss is interested in acting, but she’s warned against the drawbacks by an expert. “Johnny says, ‘You wouldn’t want to be an actress, would you?’ He just thinks it’s going from one puppet job to another.” (She has appeared in a Swedish condom commercial and has recently essayed a decorative role in Johnny Cash’s “Delia’s Gone”—”He’s such a stud,” she purrs.)

She is ambivalent about marriage, annoyed at the ease with which people get divorced, and decidedly pro children: “I’m going to have lots. I want babies! Not right now, because my career is just starting, but I’d like to have them young.” She looks forward to aging, but won’t tell me her fears. After all, she’s just 20 years old. “What do you like to do when you’re not modeling?” I ask.

“Hang out.”

“Do you have any obsessive interests?”

“No. Not really.”

“Any hobbies when you were younger?”

“No,” she says laughing. “It’s awful isn’t it? I wish I could lie, but I can’t.”

“I feel I’m further away from my purpose in life,” says Moss, as we get ready to leave, “because when I started modeling, I always wanted to be successful in whatever I did, be good at what I did. Now that it seems to have come easier, it’s more difficult to know what I want because I don’t have to strive so much.”

Moss mulls why her image has become such a burden for American women. “They pressurize girls so much into being something they’re not, that society thinks, or the media thinks they should be. If they’re pretending to be somebody else, they’re not going to be their best.”

“It’s sad,” I acknowledge.

“I know,” says Moss, wrinkling her brow. “But everyone has that phase in their life when they’re not really sure who they are, even if it’s just a short one and it comes and goes.”

“Do you have that?”

“Yeah. But it wasn’t a physical thing. It was a mental thing. When I first went to New York, I couldn’t really relate to anyone just because they were so fashiony and I was from Croydon and I was like, what are these people talking about? I just got used to it. I went back home and said to my boyfriend, ‘I think I’m going crazy. I think I’m going insane.’ And then I realized it wasn’t me at all, it was the situation.”

“What do you hope people see when they look at a picture of you?”

“That I’m not anorexic—I hate to even say the word. That I’m normal, because I am. Even though all this stuff has happened, I am normal,” the über-beauty says, pleading. “Really.”