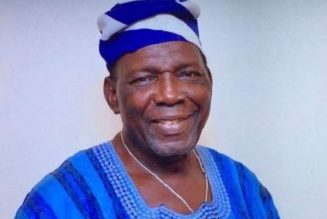

Trotter accused Yarnold, a former newspaper editor who has led the organization since 2010, of fostering a workplace that concentrates decision-making among a tight group of mostly white male allies.

“No one investigates. There’s no accountability. My complaints would just fall on deaf ears and into the hands of David Yarnold,” Trotter said. “There was no real avenue for recourse.”

Trotter told POLITICO that Yarnold’s behavior crossed a line when he suggested Trotter’s job was at stake if he did not reveal who participated in a survey that showed widespread dissatisfaction among employees. The survey was taken by 121 women, people of color, members of the LGBTQ community, people with disabilities and early career professionals with the understanding that their names would not be revealed. According to Trotter, who oversaw the survey, 66 percent of the respondents agreed that “Audubon doesn’t create an environment where diverse staff can thrive,” and 40 percent said they have seen team members or superiors “stall, de-prioritize or ignore” efforts to promote equity, diversity and inclusion.

“He said I’m going to get what I want and I am your employer,” Trotter said, describing the statements allegedly Yarnold made on an April 17 call as “a direct threat to my employment and a way to try to intimidate and coerce me into providing the data that was provided to me in confidence.”

Yarnold, in an emailed response to POLITICO questions, denied threatening Trotter or insisting that he turn over the names of the employees who participated in the survey.

“I did say to Devon that I could insist he turn over the complaints he’d received but that I wasn’t going to do so because that’s not how I manage,” Yarnold wrote [emphasis original].

Yarnold rejected the notion that the Audubon community is unfriendly to people of diverse backgrounds, while acknowledging that the organization is on a multi-year path to improving its work environment to ensure everyone has the same chance to succeed and feel at home.

“Audubon is in the throes of growth and change, and we’re eagerly becoming an Audubon for all,” Yarnold said. “We’re several years into a deep transformation around equity and inclusion, in an environmental field that’s been white-dominated for decades.”

He said staff members have “multiple avenues” to report discrimination and that Audubon is conducting equity, diversity and inclusion training for all managers and staff; working to further diversify a workforce that’s currently one-quarter people of color; adding Human Resources staff; and expanding field programs in communities serving Black residents, indigenous populations and other people of color.

Yarnold said he and Trotter were “both trying to do the right thing” in their handling of the diversity survey but that as CEO he was “legally and morally bound” to address workplace harassment and discrimination, which is why he sought more specific information about employees’ complaints.

“Our staff has been apart for eight months, and the world feels very upside down right now — all of that strains our senses of community and security,” Yarnold added. “Managing staff amid Covid-19, a national reckoning on race equity, and a contentious election, and driving cultural change at the same time is an epic challenge, but we don’t have the right to give up — we have to keep going, and that’s what we’re doing.”

Audubon is being forced to confront its own record on diversity at a time when the world of environmental activism is facing the same pressure for self-examination as media, tech and other industries. The issue is especially sensitive in the heavily white conservation field, which occupies a cultural space prioritizing organizations that lift up women and people of color. While Audubon diversified its top ranks — its executive team this year expanded from seven to nine members to boost women and people of color — current and former employees say white men remain disproportionately in control.

Trotter outlined his experience in his goodbye email to staff, some board members and outside consultants. Trotter said he faced “intimidation and threats” from a “white male hegemony” for raising concerns to higher-ups about systemic problems that had been reported to him by employees.

Trotter’s email alluded to the April 17 incident — though he did not directly reference it — regarding the anonymous staff survey. The email also cited the departure of Ferris, the former head of diversity and inclusion, saying the behavior of senior Audubon officials “broke down a powerful leader.” Ferris left the organization in March.

A former senior official, speaking on the condition of anonymity to avoid reprisals, said Yarnold’s relationship with Ferris soured after she publicly questioned Audubon’s hiring practices at a state leadership meeting last year. She argued that Audubon needed to do more to properly integrate and financially support equity and diversity efforts, which she claimed were funded by securing her own grants, the former senior official said. The official said Yarnold’s attitude toward Ferris changed after her presentation at the meeting, becoming hostile.

Two people familiar with the circumstances of Ferris’ departure say another employee leaked her copies of an email that Audubon Human Resources Vice President Chermia Hoeffner sent to Yarnold and Chief Network Officer David Ringer suggesting “talking points” for Yarnold to bring up in a future meeting with Ferris. They included sharp criticism of her performance.

“There is a clear disconnect between what she seeks to deliver and what you want to see from her,” Hoeffner wrote in an email to Yarnold, on which Ringer is copied, preparing for a Sept. 23, 2019, meeting. “Despite her protestations, you are unable to see clearly what successes her efforts have brought.”

The leaking of the emails prompted Ferris to hire a lawyer and negotiate a severance agreement, which included a non-disparagement agreement, the two people said. Ferris, who is now CEO of the Institute for Sustainable Communities, did not respond to a request for comment.

Yarnold, in his emailed responses to POLITICO questions, said Ferris resigned of her own volition.

Emails shared by an Audubon spokesperson showed that Ringer also offered qualified praise for Ferris, noting that when delivering feedback to her they “can and should acknowledge” that Ferris had “inspired staff to take action” and that “she has challenged managers to want to do more.” Ringer said he wanted to “Agree on work ahead of us for the next 6-8 months and enshrine those activities in Deeohn’s goals.”

Hoeffner and Ringer declined to comment through Audubon spokespeople.

POLITICO conducted interviews with 13 current and former employees and reviewed internal communications, video conferences, messages to staff and letters from staff to management outlining concerns about racial and gender inequity.

One employee reported being rebuffed by superiors after complaining about being on the receiving end of a racist comment by a contractor, according to a copy of the complaint obtained by POLITICO. (An Audubon spokesperson shared an email from Yarnold that disputed that account, in which Yarnold said the Society contacted the partner organization and that the person who made the comment was fired; Yarnold further discussed the matter in the email to the staff, emphasizing that employees can leave any venue where they feel “attacked or uncomfortable.”) Another employee said she began raising concerns about not having received a pay raise like her male colleagues, but was discouraged from pursuing the matter through Human Resources.

“Frankly, if you want to keep your job, you don’t want to raise any flags,” that employee said, requesting anonymity to avoid retaliation.

“We have a real culture of retribution and punishment and fear,” another woman employee said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to protect her job.

One former senior employee said Yarnold retaliated against her after she raised concerns that the organization was using restricted grant money for unintended purposes. She filed a whistleblower complaint to Human Resources about those practices. The filing alleged that Yarnold made disparaging comments about her to an outside headhunter in what the former employee contended was an attempt to tarnish her reputation.

Yarnold, in response, said he “had a discussion with two funders, who both affirmed the use of funds was consistent with their intent and was entirely appropriate. At that point, this former employee confirmed in writing that the concern had been addressed. Our board leadership was fully aware of these conversations every step of the way.”

As to the alleged retaliation, Yarnold acknowledged that the society’s executive search consultant “reached out for feedback” on the employee who had made the whistleblower complaint, and “I gave my honest evaluation so that our search partner could better evaluate candidates for us in the future. We try to have a pretty direct relationship with our partners.”

The board did not take action on the complaint, though audit committee chair Cynthia Pruett noted in an email to the complainant’s attorney that Yarnold’s actions “might be considered ill advised.”

Pruett declined to comment through an Audubon spokesperson.

A crucial backdrop for the tensions at Audubon was a diversity discussion conducted in August by a consulting firm which had a past connection with Yarnold, in which many employees were offended by what they saw as stereotypes expressed during a slide show.

In a note to the staff, Yarnold and Hoeffner acknowledged that while Audubon officials had reviewed the presentation, no one in the organization had cleared the slides.

“As many of you know, about 60 Audubon team members attended a session last week to set the stage for a series of employee-centered focus groups on Audubon’s workplace culture,” the note, posted on Aug. 25, began. “Things did not go as planned. We’ve heard from many attendees who viewed the consultants’ slides and reported a litany of inappropriate and harmful stereotypes about people. Audubon staff were hurt and shocked by some of the language, concepts, assumptions, and the facilitation approach used by the consultants.

“There is clear intersectionality between gender and race and ethnicity that should be explored and that was intended to be an important point of discussion with KMA. But, in preparation for the introductory conversation, we didn’t take the obvious step of looking at the seminar materials – a mistake given the importance and sensitivity of these conversations. We won’t do that again. We are deeply sorry. We disavow the hurtful stereotypes and characterizations that were presented last week and in the follow-up materials. None of those materials represent the views of the National Audubon Society or its management team, including the two of us.”

Yarnold said in his emailed response to POLITICO questions that KMA was hired through a competitive bidding process, and that he “had a professional relationship with the firm more than 20 years ago in a different job.”

Throughout the period of discord, Yarnold said, he has kept the Audubon board informed of all complaints and his efforts to handle them.

“I’ve been telling our staff, our board, and our constituents that this is deeply difficult culture-change work, but the path leads only forward,” he said. “We’re taking on issues that many for-profits and non-profits duck. Few organizations have the courage to take on change of this magnitude and see it through. This is some of hardest and riskiest transformation an institution could attempt, but we’re fully committed to meeting this American moment.”