When the end came, it was just like Tom and Mary had imagined. Supply chains started to crumble. Millions of Americans lost their jobs. Grocery stores ran out of food. The nearly retired couple wasn’t going to wait for society to collapse. They hopped in their camper van and drove 19 hours to South Dakota. “To come here and experience it in person is like walking the Grand Canyon for the first time,” Tom says. But it’s not the Grand Canyon. It’s a doomsday bunker.

Tom and Mary are living at xPoint, an abandoned military facility-turned-survivalist community at the base of the Black Hills in Fall River County. Miles of plains stretch out in all directions, connected by 100 miles of private road. Along the skyline, steel doors tucked into grassy knolls indicate the openings to the bunkers. It looks like an abandoned ranch, which is more or less what it was until a real estate mogul purchased it for the price of $1.

The idea for Vivos, a global community of apocalypse bunkers, came to CEO Robert Vicino nearly four decades ago in a moment of inspiration that featured a “crystal clear” female voice in his head. It said, Robert, you need to build deep underground bunkers for people to survive something that is coming our way. He filed it away until 2008, (the year Obama was elected) when the time was finally right to start building.

Vivos has survival campuses in South Dakota, where Tom and Mary live, and Indiana. These are for the downmarket bunkers that cost roughly $35,000 each. Vivos Europe, in contrast, is marketed as “the ultimate life assurance solution for high net worth families.” Apartments there cost upwards of $2 million.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19963658/vivosxpoint_landscape5.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19963636/Vivos_xPoint_Bunker_Showroom.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19963663/Vivos_xPoint_Bedroom.jpg)

While Vivos has been profiled as a luxury bunker facility, Vicino says most of his customers are middle-class. He describes them as “well-educated, average people with a keen awareness of the current global events and a sense of responsibility knowing they must care for and protect their families during these potential epic and catastrophic times.” Based on the people I spoke to for this story, it seems they are also all polite, white, and Trump-supporting.

As COVID-19 brings the real estate market to a standstill, demand for doomsday bunkers is at an all-time high (or low since the structures are underground). The shelters were once signifiers of fringe prepper communities worried about the coming apocalypse. During the pandemic, they’ve become vacation homes. “People thought we were crazy because they never believed anything like this could happen,” says Vicino. “Now they’re seeing it. Everybody is a believer.”

Bunkers give people a sense of control, the feeling that they can fend for themselves. Their newfound popularity mirrors an overall trend toward more disaster preparedness where behaviors that used to seem paranoid, like stockpiling food, look normal (if inadvisable) in light of the ongoing pandemic.

But the trend also has a darker side: the sense that people need to protect themselves against the other. “The have-nots are going to go after the haves,” Vicino tells me. “They will knock on your door. And if you don’t have enough to give, it gets ugly.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19963632/vivos_xpoint_site_plan.jpg)

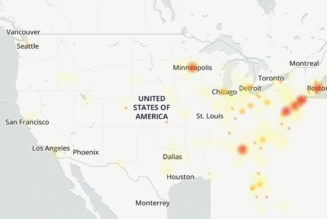

Vicino doesn’t specify who the “have-nots” are, but his language echoes a specific type of pandemic-induced tribalism that’s typical in parts of white America. Since March, Stop AAPI Hate, an organization that tracks discrimination incidents, has received almost 1,500 reports of verbal harassment and physical assault from the Asian American community. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also found that COVID-19 is hitting racial minority groups harder than it is white communities. African Americans, in particular, are being hospitalized and dying at disproportionately high rates. Yet, prepper communities tend to be predominantly white.

Vivos, for its part, says it has members from “all walks of life,” and emphasize an array of religious backgrounds. Dante Vicino, Robert’s son, says “there is the expected middle-age conservative demographic, but we have political moderates and liberals, too.”

Prior to the pandemic, Vicino wasn’t making money off Vivos. “My goal is not to get rich off of this. I already was rich,” he explains. When the novel coronavirus started to spread in the United States, however, inquiries about new bunkers began to climb. At xPoint, the facility in South Dakota, Vivos has sold more than 50 bunkers and still has 500 to go. “We’re selling almost one a day right now,” Robert tells me. Two weeks ago, he says he made more than a million dollars on a single Friday. The following Monday he made $500,000.

Vivos isn’t screening incoming members for the novel coronavirus. Vicino says the tests aren’t yet “valid,” and he trusts people to make their own decisions. “If they need to wear a mask, they wear a mask,” he says. “If they need rubber gloves, they’re wearing them. At the end of the day, it’s their bunker.”

Some bunker companies have capitalized on coronavirus fears and begun marketing air filtration systems that can screen out COVID-19 particles. Rising S Company, a Texas-based disaster preparedness group, calls itself the leader in “nuclear, biological and chemical air filtration systems” and says it has the “experience needed to help stop the spread of this deadly virus.” Survival Condo, a luxury bunker maker, says it has a system that “can filter out pathogens like COVID-19.” Even Vivos says its shelters come with “air scrubbers to eliminate all pathogens and radioactive particles before entering the underground space.”

“We had a lot of snake oil companies in the indoor air space before,” says Jeffrey Siegel, a professor of civil engineering at the University of Toronto who specializes in air filtration systems. “Now we have orders of magnitude more of them making specific claims about COVID.”

Siegel says that while the filters might be effective for cleaning air that comes into the bunkers, they don’t address the major concerns about how the coronavirus is actually spread. “In terms of the COVID risk, I don’t worry about outside air at all,” he says. “I worry about indoor air, and I worry about being in the space with someone who is infected.”

Siegel also says that installing fancy air filters but not testing people who’ve traveled from big cities is foolish, if not downright dangerous. “If you’re addressing the airborne route and not addressing close contact, it’s silly. We shouldn’t even be talking about it,” he says. “If the bunkers are poorly ventilated, then they’re actually more hazardous from a disease point of view than a well-ventilated house that’s not doing anything to treat outdoor air.”

For Michael, Megan, and their two kids, the pandemic was the final push needed to move out to xPoint permanently. The family of four had been living in New Carlisle, Indiana — a town of under 2,000 people — but they wanted to be even more rural. Two years earlier, they’d purchased a bunker at xPoint. Now it was time to take the leap.

The decision dated back to 2012 when one of their daughters got in a terrible accident at the Indiana State Fair. She was run over by a truck and suffered a crushed pelvis and two broken arms as well as numerous internal injuries that required almost 20 surgeries to recover. The experience left Michael and Megan with the knowledge that they needed to learn to fend for themselves — anything could happen at any time. “If you look at Katrina, the flooding in Texas, governments can’t control the world,” Michael says. “After all the stuff unfolds and you see the YouTube videos, it’s foolish for anybody to think you could depend on the government.”

Now that they’re in South Dakota, their days are simple and satisfying. In the morning, Megan homeschools their two girls, while Michael begins working on the bunker. He’s building a wood floor over the concrete and putting in a plumbing and electrical system. In the afternoons, Megan and the girls tend to the vegetable garden. Soon, they’ll start canning their own food. The routine is reminiscent of Little House on the Prairie or that of a minimalist Instagram influencer, except with armored doors instead of linen curtains. “The whole experience of building the bunker and being out here is fun and exciting,” Megan says. “Every day is an adventure.”

While many Vivos customers are currently building out their bunkers, Tom and Mary are one of the only other couples living at xPoint permanently. They bought their shelter three years ago after reading Patriots: A Novel of Survival in the Coming Collapse, which is popular among prepper communities. The book is a work of fiction; it tells the story of a global economic collapse where the United States becomes “gripped” in a “continual orgy of robbery, murder, looting, rape, and arson” where “hordes of refugees and looters pour out of the cities.” Tom says, “It opened my eyes to the level of vulnerability that most people have if something happens and food can’t be delivered to the store for whatever reason.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19963598/IMG_20200501_193048.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19963610/IMG_20200501_161053.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19963602/IMG_20200501_161704.0.jpg)

When the couple found out about xPoint, they were intrigued but wanted to see what the community was like before committing. “It’s one thing to hide away in a hole in the ground and stay there for months, but there are some things I can’t do myself,” Tom says. “Community is going to be important because you’re going to need help.”

He decided to attend xFest, the Fourth of July festival Vivos holds to welcome prospective members. There, he found a group of like-minded individuals — mostly families and couples like himself and Mary — that he knew could form the basis of a survival network. He and Mary signed the paperwork, planning to use the bunker as a home base once they retired and began traveling across the United States.

But the pandemic shifted that timeline up considerably. In February, as cases began to grow in the US, Tom and Mary watched in horror as the signs of collapse that they’d read about in Patriots started to play out before their eyes. “We could look out the window and see people going about exhibiting behavior that was going to spread the virus like crazy,” Tom says.

Of course, they were more prepared than most, but they hadn’t anticipated situations like a toilet paper shortage. “Toilet paper is important to have, don’t get me wrong, but there were people loading up carts of toilet paper and don’t have food in their mouths,” Tom says.

The scarcity made Tom and Mary feel exposed, especially being so close to a big city. “We recognized that if we did have a full-on collapse of society as we know it, that we would be very vulnerable in our home west of Atlanta,” Tom says. They decided it was time to move.

Now, like Michael and Megan, they are living completely off the grid. XPoint has no power or electricity, and the closest town is 30 minutes away. To Tom and Mary, it’s heaven — no more blaring sirens or crowds of people. “We got here, and right away, we realized we had made it,” Tom says. “It was just this really great relief to know we were in a safe place and could manage ourselves.” He’s working on building out the bunker with everything it needs to become a livable home. Already, he’s created his own power system and has a solar array and a wind turbine. “I’m his helper,” Mary says. They don’t plan to go back to Georgia anytime soon.

While the pandemic prompted Tom and Mary to move out to their bunker and has brought in an influx of new clients, Robert Vicino is convinced it’s only the beginning. “It’s the ripple effect,” he tells me. “People will become predators.” Vicino paints a picture of looting and mayhem much like what’s described in Patriots. “The have-nots will go after the haves,” he says again. “There will be hell zones.”

If this happens, Vicino claims Vivos will be the ultimate safe zone. “I would hope that the seeds of the future society of America come through Vivos,” he says humbly. “It may sound prophetic, but it could happen.”