Contrary to popular belief, Britpop was not a subgenre. It was also not a catchall for every bit of culture being manufactured in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. (That would be “Cool Britannia,” and like Britpop it almost exclusively applied to English entities.) Instead, Britpop was originally a press-driven crusade to champion domestic talent that represented the customs and lifestyle in their music.

The credit (or blame) for the whole thing really goes to journalist Stuart Maconie, whose “Yanks Go Home” cover story in the April 1993 issue of Select framed indie acts like Suede, Pulp, Saint Etienne and the Auteurs as an antidote to the “bad grunge” that was “killing British music.”

Although Suede frontman Brett Anderson graced the Select cover, he publicly derided the feature, distancing himself and the band from some movement that had insinuations of nationalism. (See Morrissey’s questionable antics the year before.) Nevertheless, Suede were proclaimed the new face of a musical revolution beginning in the UK.

Meanwhile, Suede’s adversaries Blur were becoming the very manifestation of Maconie’s article. Following a disastrous tour of the US, Blur were flirting with something they called the “British Image” to promote their second album, Modern Life Is Rubbish. Led by the Kinks-y single “For Tomorrow,” the album proved to be the blueprint for what was to come: jaunty indie pop songs that celebrated and satirized traditions like the Sunday roast, sugary tea and the bingo.

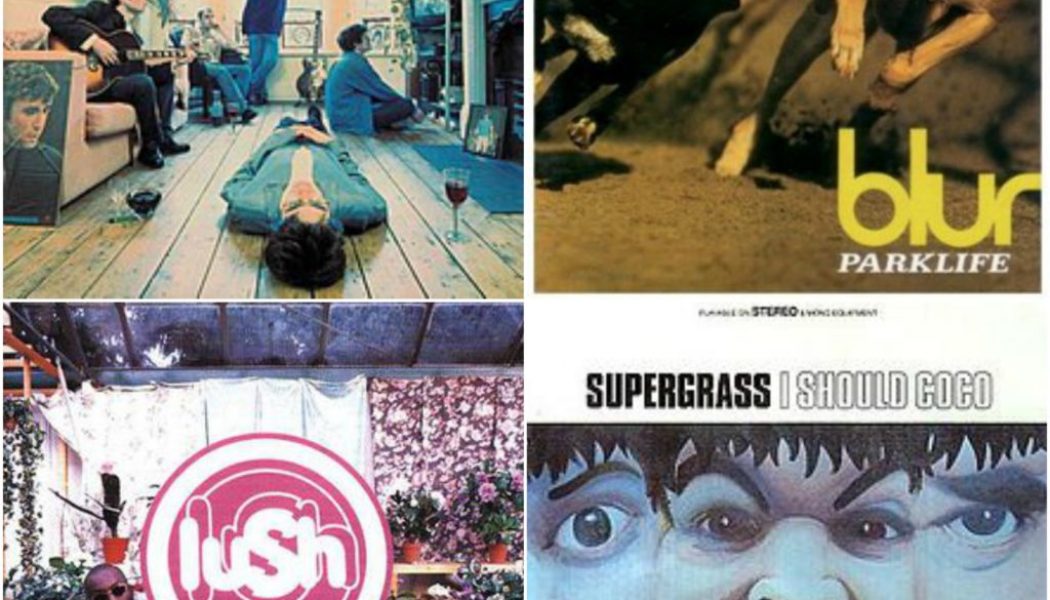

But it was the following year, in 1994, when Britpop entered the public’s consciousness and vocabulary. With Blur’s third album, Parklife, and the debut by Manchester’s Oasis, Definitely Maybe, Britain’s indie music scene exploded. New bands ([email protected], Northern Uproar) popped up across the country to benefit from the craze, and older bands (Ocean Colour Scene, Lush) changed their sound to reflect the times. Everyone who wanted to be seen would get drunk in Camden at the Good Mixer, or maybe go out for some dancing at Blow Up. It was a time for indulgence.

As Britpop crossed international waters, so did its boundaries. In North America, the press got lazy and applied the term to just about anything from the UK. And so the net was widened to include revolutionary space rock (Radiohead, the Verve, Spiritualized), Welsh alternative rock (Manic Street Preachers, Super Furry Animals, 60 Ft. Dolls, Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci), bands that worshipped American music (Ash, Teenage Fanclub, Placebo), the seasoned songwriter, aka “dadrock” (Paul Weller, Edwyn Collins), and even the odd American act (Nancy Boy).

Britpop had no clear end date, but the party started to fizzle toward the end of 1996. With Pulp’s Different Class bringing on the last call, Britpop began its descent. Pulp themselves lost interest and retreated into a dark place for their next LP, 1998’s This Is Hardcore. Blur pulled a 180 and embraced American music, palling around with Pavement while making their indie rock-indebted self-titled album. Oasis were so committed to the Brit script that they parodied their own sound on the ostentatious, cocaine-fueled Be Here Now. Elastica went AWOL and never truly returned. And soon Britpop was more or less a punch line attached to the likes of the Spice Girls, Tony Blair and Austin Powers.

Nostalgia, however, is one of our favorite pastimes and Britpop lives on in our memories. This fall sees the 25th anniversaries of many significant albums of the time – the HELP compilation, Blur’s The Great Escape, Oasis’ (What’s the Story) Morning Glory?, [email protected]’s Nuisance, and Pulp’s Different Class – as well as While We Were Getting High: Britpop and the ‘90s, a book of photos by Kevin Cummins, the former NME photographer who was front and center. To commemorate these milestones, we take a look at the best albums from the short-lived era of Britpop.

25. Various, HELP

Britpop had no shortage of compilations, and while most of them were solely out to make money off the hits, there was one that stood out from the rest. Compiled by War Child UK, a not-for-profit charity that helped children in need in war-torn countries, HELP was the first in a series of releases collecting new, unreleased and rare tracks by big name acts. Aiding Bosnia and Herzegovina, HELP was astonishingly recorded at London’s Abbey Studios in just one day (Sept. 4, 1995). The organization and logistics involved in pulling it off were second only to the talent recruited. Featuring a range of artists (Portishead, Sinead O’Connor, Radiohead, Massive Attack), the inclusion of Blur, Suede, Oasis and the Boo Radleys definitely felt like an opportunity to utilize Britpop’s popularity for a good cause.

24. Whiteout, Bite It

Undoubtedly the most obscure band on this list, Whiteout were also one of the only Scottish bands to even register as Britpop. They were also incredibly unlucky. After signing to Silvertone, the label best known for discovering Stone Roses (who later sued them), Whiteout basically failed right out of the gates. A co-headlining tour with Oasis in 1994 found the Scots immediately overshadowed by the headline-grabbing Mancs. While there was “Whiteoutmania” in Japan, the rest of the world passed on the band’s debut album. But Bite It could very well be Britpop’s great, lost treasure. With strong nods to the Faces, the Byrds and Big Star, Whiteout were clearly doing their own retro thing (one that countrymen Teenage Fanclub would end up adopting), resulting in high points like the easy-going flow of “Jackie’s Racing” and the feel-good strut of “Altogether. It likely wasn’t considered fashionable at the time, but Bite It managed to age better than most of the albums that initially outshined it.

23. These Animal Men, (Come on, Join) The High Society

Technically, Brighton’s These Animal Men were better known as poster boys for the shorter-lived New Wave of New Wave (NWONW) movement, which eventually conceded to Britpop’s ascendency. But they had the three-minute pop songs, tabloid-baiting sound bites and the glamorous looks to fit in (expensive haircuts, eyeliner, Lonsdale tees, Adidas sneakers and leather) – all that and a member named Hooligan. They thought they would become the next MC5, but instead, TAM would only be remembered as a gang of beautiful, hedonistic mod-punks. Their debut LP, (Come On, Join) The High Society, remains to be criminally overlooked, despite its unparalleled vitality and bona fide guitar anthems such as “You’re Always Right,” “Too Sussed?” and “Flawed Is Beautiful.”

22. Marion, This World & Body

Hailing from Macclesfield, the same Manchester ‘burb as Ian Curtis, Marion were more aligned with the melodramatic flair of Suede and the coursing rock of early U2 than Joy Division. In frontman Jaime Harding, Marion had one of the best voices around, gifted with the ability to soar and emote like his hair was on fire. Their debut album, This World & Body, sought to steer clear of Britpop’s party vibe. Instead, the music focused on brooding, valiant rock songs that teetered on the edge of self-destruction, thanks to guitarist Phil Cunningham’s (now with New Order) urgent playing. Tracks like the “Pretty Vacant”-biting “Time” and near-hit “Sleep” were raucous yet tragically romantic bangers – the latter even pulling off a heroic harmonica solo, an act that was likely prohibited by Britpop’s gatekeepers.

21. The Bluetones, Expecting to Fly

Hyped to no end by the UK press leading up to the release of their debut album, Hounslow’s the Bluetones weren’t a flashy bunch, but they knew how to write amiable pop songs and a frontman who danced funny. Whatever the Bluetones had going for them, it shifted a lot of units. Debut album, Expecting to Fly went to #1 (knocking Morning Glory off its throne) on the strength of its succession of singles, all of which were hits. Singles “Cut Some Rug” and “Slight Return” introduced a baggy shuffle not heard since Madchester, hence them getting tipped by many as the next Stone Roses (though they were more Second Coming than self-titled). Yes, Mark Morriss had a bit of an Ian Brown lilt to him, but truth be told, his feather-soft vocals were regularly drowned out by Adam Devlin’s guitar play, a layered mix of Rickenbacker jangle and beefy, fuzzed riffing that was easily the most captivating aspect of the band.

20. Cast, All Change

When Liverpool’s Cast formed in 1992, they were somewhat of a two-man supergroup. John Power played bass in the legendary proto-Britpop band the La’s, who experienced some fame with their hit “There She Goes” before burning out. Peter Wilkinson, on the other hand, played bass in an early incarnation of Shack, a cult band that had briefly broken up. When Cast became a four-piece, Power assumed the role of singer/songwriter and demonstrated his ability to write catchy and propulsive guitar pop. Produced by John Leckie (Stone Roses, Radiohead), their debut album, All Change, blended their Merseybeat, ’60s psych and power pop influences with the compelling harmonies of their previous bands. There was nothing sexy or even trendy about Cast, but in keeping it simple they let the big, juicy hooks of “Finetime,” “Walkaway,” and, their best single, “Alright” do all of the convincing. Noel Gallagher was such a fan, he not only invited them on tour, but also called their music “a religious experience.”

19. Lush, Lovelife

I’m sure if you asked the members of Lush if they intended to bounce from one overblown music scene to another, they’d roll their eyes. But in their attempt to leave shoegaze behind, the London four-piece’s pivot to a cleaner, more melodic sound was unwantedly slapped with the Britpop tag. The group’s fourth album, Lovelife, mostly abandoned the reverb/delay effects of its predecessors, in favor of janglier guitars, stronger hooks and sing-along choruses. It’s hard to deny that relatable dating dramas like “Single Girl” and “Ladykillers” weren’t ripe for Britpop inclusion, but then there was the flirty “Ciao,” a duet between Miki Berenyi and the Britpop Prince himself, Jarvis Cocker. In the end the reinvention brought them their greatest success, a Top 10 album and three Top 40 singles.

18. Sleeper, Smart

Britpop had its fair share of sex symbols, but none more visible (or exploited) than Louise Wener of Sleeper. While the band were regularly featured in the UK press, the gaze it placed on Wener was so crass it was impossible to distinguish her male bandmates from one another. (Wener discussed how she was treated in her memoir, Different for Girls: My True-life Adventures in Pop, which is worth a read.) It’s unfortunate because Sleeper had some great tunes, and none better than the ones on their 1995 debut. Smart established Sleeper as a second-tier Britpop act whose hooky guitars, seductive choruses and sloganeering fared well in both the mainstream and indie charts. As an outspoken, confident frontwoman, Wener wasn’t afraid to own her sexuality, adopting a lusty affectation (see the hit, “Delicious”), but her casual observations weren’t one-track – few songwriters could rhapsodize about daily life the way she did on “Inbetweener.” Shame almost everything they did was compared to Elastica.

17. [email protected], Nuisance

One of the era’s most divisive bands, [email protected] emerged from Camden Town in late 1994 like some test-tube creation designed specifically to capitalize on Britpop’s growing popularity. That they secured a Melody Maker cover before releasing even a note of music drew plenty of ire from the naysayers, but there was something alluring about this gang of “indie chancers.” Ridiculed for flaunting their sense of style over substance, their debut album Nuisance did a commendable job of fulfilling the glam-mod agenda they were modeling. For a band that was rushed so quickly into the limelight, songs like “Around You Again,” “I’ll Manage Somehow,” and “Sleeping In” packed enough chops, cheek and wit to prove they had at the very least established an identity of their own. Nuisance may not have been “somewhere between Never Mind the Bollocks and Hunky Dory,” as they described it, but it was an ambitious, accomplished debut, and not the punch line some remember it as (see a band called Northern Uproar).

16. Echobelly, Everyone’s Got One

London’s Echobelly were singled out almost immediately because they were arguably the only multi-racial, multi-gendered band in their scene. If it wasn’t frontwoman Sonya Madan’s gender that the press was asking about, it was her Indian heritage or the fact that a lot of people thought she sang like Morrissey. Such pigeonholing seemed to help build her strength as a lyricist. On the band’s debut, Everyone’s Got One, Madan oozes with confidence as she sings about hot button topics such as abortion (“Bellyache”), racism (“Call Me Names”) and female empowerment (“Give Her A Gun”). Madan’s rich, impassioned voice is backed by the strident, yet melodious dual guitars of Glen Johansson and Debbie Smith, formerly of shoegaze noiseniks, Curve. Those comparisons to the Smiths never made much sense, especially with a song like “I Can’t Imagine the World Without Me” up their sleeve, a rollicking bit of power pop that contrasted a sludgy bass riff with roaring trumpets.

15. The Divine Comedy, Casanova

Hailing from Northern Ireland, the Divine Comedy were a curious addition to the Britpop pool. Frontman/composer Neil Hannon had next to nothing in common with his peers, taking his cues from Nöel Coward and Michael Nyman rather than Bowie or the Davies Brothers. On their previous albums, Hannon proved he could write a good pop song, but nothing quite compared to the ones he composed for his masterpiece, Casanova. The Divine Comedy’s fourth album is an exquisite orch-pop romp about a horny lothario done in the style of Scott Walker’s early solo albums. It’s satirical, hilarious and regularly absurd (“The Frog Princess” incorporates the French national anthem), but such a joy from beginning to end. “Something For the Weekend” is one of the finest singles of its time, with its galloping rhythm, buoyant string and horn combo, and Hannon’s pretentious voiceovers. He even took aim at Britpop with the sardonic Bacharach spoof, “Becoming More Like Alfie,” a commentary on its problematic lad culture. Ironically enough, it became a hit with the lads.

14. Gene, Olympian

One of Britpop’s defining characteristics was paying homage to influences, and no band did it as patently as London’s Gene. From the classic, elegant photography in the artwork, to the Morrissey ‘n’ Marr-lite mimicry of Martin Rossiter and Steve Mason, Gene were the next great hope for anyone still holding out for the Smiths to reform. At times, the UK press could be cruel about it (“Gene are virtually a Smiths covers band and no amount of brazening it out should forgive that fact,” NME wrote), but damn, could they ever write a convincing Smiths facsimile. Despite the unrelenting comparisons, Olympian was as poised as any debut album in 1995. Singer/songwriter Rossiter was the truest romantic, crooning about a lover, the city or his vices with equal parts grace and swagger. As precious and tender as Gene could get (see the title track), they could also dial-up things up on cuts like the out-and-proud “Left Handed” and the feisty single, “Haunted By You.”

13. Longpigs, The Sun Is Often Out

Sheffield’s other Britpop band, Longpigs, almost never had their shot. First, a nasty tour van crash left frontman Crispin Hunt in a three-day coma, then came the dissolution of their label Elektra in the UK, which left their debut album in limbo. Lucky for them, U2’s Mother imprint agreed to put up the money to buy it back, and a couple of years later, Longpigs could finally release it. With its excess of singles (five in total), The Sun Is Often Out should have catapulted the band to superstardom, but instead they had to settle for a modest success, which included a string of Top 40 singles. It’s a shame because their “art-grunge,” as they called it, felt like a shot in the arm for Britpop. This was an album alive with composure and passion, led by the feverish falsetto of Hunt, who one minute could go feral on “Jesus Christ” and “She Said,” then turn around and drop a bruised ballad like “On and On.”

12. Oasis, (What’s The Story?) Morning Glory

By the time Oasis were ready to unveil their second album, their momentum was unstoppable. Although they (rightfully) lost “The Battle of Britpop” in the singles charts to Blur, Oasis had become Britain’s biggest band, both domestically and abroad. Released just 13 months after Definitely Maybe, (What’s The Story?) Morning Glory revealed itself to be more immediate, more accessible, and more expensive than its predecessor. No longer were they looking to rule Britain, they wanted to be the biggest band in the world – a goal that would achieve for at least a year or two. Noel Gallagher continued to ape his influences (Gary Glitter, T-Rex, Slade, the Beatles), but he also broadened his scope as a songwriter. While continuing to produce the guitar-led, pub sing-alongs that made him famous (“Some Might Say,” “Roll With It”), he also found success in penning softer, more personal AOR rock (“Wonderwall,” “Don’t Look Back In Anger”) that would eventually become his bread and butter. Some critics felt the band rushed it, citing Noel’s lyrics as lazy and hollow, but only Oasis themselves felt they could outdo an album like Definitely Maybe.

11. The Auteurs, After Murder Park

If there were such a thing as an anti-Britpop band, the Auteurs would have been first in line to claim its title. The band’s outspoken and curmudgeonly frontman Luke Haines was so opposed to the idea that he famously penned a 2009 memoir called Bad Vibes: Britpop and My Part in Its Downfall. Nevertheless, the Auteurs were one of the first bands associated with the movement, albeit by presenting a cynical, more twisted, and perhaps a more accurate depiction of life in England on 1993’s New Wave and 1994’s Now I’m A Cowboy. That he recruited indie rock’s chief grump, Steve Albini, to record the Auteurs’ third album at Abbey Road Studios says a lot about Haines: he wanted to maximize his miserable rock music. After Murder Park finds Haines all sharp-tongued and scornful, ready to spin tales about dead children, choking on a whale bone in a Cantonese restaurant, underage brides, sailors lost at sea, and not one but two plane crashes. He even hisses at the end of “New Brat in Town.” It’s as far from Parklife as it gets, however, “Unsolved Child Murder” is one of the unlikeliest earworms you’ll ever come across.

10. The Charlatans, The Charlatans

By the time Britpop rolled around, the Charlatans were ready to move on to a new chapter. They had left behind the baggy sound of “Madchester” that made them stars but hit a wall with 1992’s disappointing Between 10th and 11th and suffered personal setbacks during the making of 1994’s Up To Our Hips (Martin Blunt suffered a nervous breakdown, while Rob Collins was arrested for armed robbery). However, when they returned the next year with an eponymous album, nothing could stop them. Channeling their classic Brit rock forebears, the Charlies went full-on rock’n’soul. The vibes this time around were overpoweringly positive as they tamed the Stones’ “Sympathy” for “Just When You’re Thinkin’ Things Over,” attacked the Hammond on the funky rave-up “Bullet Comes,” and went into the swamp for the bluesy “Toothache.” Going into the charts at #1, the album proved to be the triumphant return to the top they needed, just as their world would come crashing down the following year with Collins’ death.

9. Suede, Coming Up

Suede may have laid the foundation for Britpop, but they sure wanted nothing to do with it later on (frontman Brett Anderson literally moved neighborhoods to avoid it entirely). But once original guitarist Bernard Butler quit the band, Suede needed an overhaul: they recruited a new guitarist, the teenaged Richard Oakes, and added Neil Codling (drummer Simon Gilbert’s cousin) on keys, and looked to have some fun. Exorcising himself of the torture and paranoia that fuelled 1994’s Dog Man Star, Anderson returned with a euphoric pop album that divulged tales of hedonistic binges, frivolous sex and electric love. With Oakes cranking up the treble, Suede went full glam on the sordid stompers “Trash,” “Filmstar” and “Beautiful Ones.” But Anderson wasn’t just about shaking his bits to the hits, balancing his self-indulgence with a sublime stroke of balladry with the beatific offerings of “Saturday Night” and “By the Sea.”

8. Pulp, His ’N’ Hers

By the time Pulp achieved their breakthrough, Jarvis Cocker had spent half of his life trying to reach it. With a revolving door line-up since 1978, Pulp were solidified with the addition of bassist Steve Mackey a decade later, earning accolades with the singles “My Legendary Girlfriend” and “O.U.” Once they signed to Island, Cocker finally had an audience to hear him spin tales of dreary, every day life in Sheffield. His confessional approach to lyric writing was exotic and carnal; the seductive narratives of “Babies,” “Acrylic Afternoons” or “Pink Glove” could have easily have been adapted into a daytime soap opera arc. The delicious, kitschy melodrama is only matched by the band’s performance: Cocker’s transitions from breathy whispers to histrionic falsetto, Russell Senior’s whooshing violin strokes, Candida Doyle’s arpeggiating laser synths, and the fluid rhythms of Mackey and Nick Banks. With an assortment of vintage toys to play with, they exploited their retro tendencies, mixing disco, glam and new wave to create a fluorescent dance floor paradise.

7. The Boo Radleys, Wake Up!

Over the course of their decade-long run, the Boo Radleys continuously evolved their guitar pop sound with each of their six albums. At the time of their ambitious 1993 breakthrough, Giant Steps, they were dabbling in dub, shoegaze and noise-pop, but it was the orchestral pop side that emerged as the winner. For their fourth album, Wake Up!, they (mostly) dropped the genre tinkering in order to fully embrace a more unified sound that blended power pop, Motown, psych and soft pop influences that, no surprise, just so happened to align perfectly with Britpop (see “Charles Bukowski is Dead” for irrefutable evidence). The album proved to be their greatest commercial achievement led by the success of its effervescent lead track. A bright-eyed and bushy-tailed anthem that even wormed its way into Stevie Wonder’s ear, “Wake Up Boo!” became a ubiquitous hit and made them an overnight commercial success.

6. Blur, The Great Escape

Blur weren’t built to go head-to-head with Oasis. They were an art-pop band whose most brazen attempt at writing a commercial hit won them “The Battle of Britpop.” For a brief moment, they seemed to enjoy winning the awards and filling the tabloids that Parklife’s success brought them. However, Blur weren’t “for the people” the way Oasis were. Frontman Damon Albarn was always too smart for his own good, and Blur’s answer to Parklife was to go weirder, sadder, and braver than before. “Country House” may have fooled listeners into expecting more of the same, but The Great Escape is full of whimsical left turns, each one as daunting as the next (credit the innovative guitar work of Graham Coxon, Britpop’s best guitarist). Albarn’s third-person narratives really elevated his gift as a lyricist, giving life to complex individuals to confront his feelings of overpopulation, suburban tedium, suicide and paranoia. The gleeful, sing-along moments are big and boisterous (“Stereotypes,” “Charmless Man,” “Entertain Me”), but it’s at the other end of the spectrum, the melancholy of “Yuko & Hiro” and “The Universal,” which may be the best song in all of Blur’s catalog, where Blur are most triumphant. The Great Escape managed to demonstrate the kind of complexity and dexterity few of their contemporaries were capable of.

5. Supergrass, I Should Coco

Oxford’s Supergrass debuted out of thin air with “Caught By The Fuzz,” a mighty gust of ’77-tinged punk about minors getting nabbed for drugs. At first, everyone assumed the trio were the second coming of Buzzcocks, but little did they know that Supergrass had tricks up all six of their sleeves. Led by the then-teenaged, mutton-chopped Gaz Coombes, Supergrass were as unique as a rock band could be at the time. Fresh, mop-topped, young faces mimicking the Small Faces, the Beatles, the Stones, Madness, the Jam, Bowie, Kinks, and the Who, you name it, simply for kicks. Every song on I Should Coco is a knockout: from the manic punk of “Sitting up Straight” to “Alright,” the feel-good smash hit of that summer. “We’re Not Supposed To,” a sped-up filler cut where they sound like the Chipmunks singing McCartney, could have gone Top 40 if they had made it a single. So in-demand were Supergrass, that even Steven Spielberg wanted a piece, offering to make them The Monkees for a new generation. They wisely turned him down.

4. Elastica, Elastica

One of the few Britpop acts to make a big splash in the U.S., there was nothing cooler than Elastica and their monochromatic palette. Thanks to Justine Frischmann’s romantic affiliations with both Suede’s Brett Anderson and Blur’s Damon Albarn, and a brief affiliation with the New Wave of New Wave, Elastica were primed and ready to become sensations by the time their debut LP dropped in March 1995. With their androgynous look and biting wit, Frischmann, Donna Matthews and Annie Holland were the perfect antidote to the laddism running rampant within Britpop. In spite of pinching riffs from Wire and the Stranglers (settlements were paid out, credits given), their nervy punk sound and new wave lean made them a refreshing alternative to just about everything else. With “Stutter” and “Connection” they had mega-hits under their belt, giving them enough clout to fend off any purists who wrote them off as thieves.

3. Oasis, Definitely Maybe

Simply put, the debut album by Oasis changed the game for British music. Britpop was already underway before its release, but with Definitely Maybe, the Gallagher brothers initiated the kind of pop culture moment not seen in the UK since Beatlemania. With their immediate hooks, arena rock ambition and working-class charm, Oasis quickly established themselves as the band for every Briton. Their constant feuding – between the brothers and almost every other band around — baited tabloids and made them overnight rock stars, and yet nothing was ever bigger than the music itself. From “Supersonic” and “Shakermaker” to “Live Forever” and “Cigarettes and Alcohol,” Noel Gallagher constructed his songs as relatable manifestos, while Liam Gallagher embodied the great frontmen before him, singing them with unrelenting swagger and charisma. Of course, it wasn’t all that original, but nobody was using a wall of sound layers, overstated guitar solos and booming, nursery-rhyme choruses as effectively and aggressively as Oasis. Definitely Maybe became the fastest-selling debut album in the UK, while spawning numerous copycat bands (see “Noelrock”), but its influence and magnitude still resonate today.

2. Blur Parklife

Blur’s second album, Modern Life Is Rubbish, arrived a year before Britain was ready to embrace it, but by the time they were ready to follow it up, the nation was all ears. The band knew they were onto something with this “British image” model they were selling, and so for their third album, Blur continued on their path, tapping into their nation’s cultural zeitgeist. This time though, they were brimming with the assuredness, the wit and the ambition to take it to the masses. Released weeks after the death of Kurt Cobain, Parklife received a hero’s welcome by the British public, hot on the heels of their hit single, “Girls and Boys,” a sleazy, Euro-pop banger for the weekender set. Inspired by the skewed pop of XTC and Madness and the classic sensibility of the Kinks, Damon Albarn and his bandmates constructed a loose concept album that explored English life through a lens: the sarcastic Cockney piss-take of “Parklife,” (featuring Quadrophenia’s Phil Daniels), the glamorous, upper-class baroque pop of “To the End” (with Stereolab’s Lætitia Sadier), the junkie’s sorrow of “This Is A Low,” the romantic indolence of “End of a Century,” as well as one last flick of the vee to the U.S. and its influence (“Magic America”). For an all-too-brief moment there, both Britpop and Britain belonged to Blur.

1. Pulp, Different Class

Britpop was only really supposed to be a two-horse race. “Blur versus Oasis,” the headlines wrote during the summer of 1995, as the two heavyweights squared off in the singles chart. Little did anyone know that Jarvis Cocker and his band Pulp were set to make things interesting. Pulp had already won the hearts of Britain that summer, taking Glastonbury by storm when they filled in for the absent Stone Roses. With that triumphant gig and “Common People” reaching No. 2 in the charts, Pulp were undergoing a pop culture moment. They even had a national controversy to help solidify their celebrity status. When Different Class landed, the pendulum began to swing. Pulp were the misfits he sang of, making a move. All of a sudden it was Cocker’s face plastered everywhere, with the press appointing him Britpop’s new hero. As the songwriter, Cocker was in full voyeuristic mode, detailing the class stratification he witnessed in London through various outsiders: the vengeful lowlife in “I Spy,” the foul libertine in “Underwear,” two lovers meeting by chance in “Something Changed.” Britpop was built of fleeting moments, but with Different Class, Pulp captured the one moment that would stand the test of time. They traded in the exclusive, high-gloss retro of His ‘N’ Hers for something organic and universal, presenting an album of warmth, curiosity and pleasure for the public to experience. It won the Mercury Prize, but more than anything, it made Pulp the one band that everyone could agree on. For many, the answer to “Blur or Oasis?” became “Pulp.”