The risk assigned to Kenya’s sovereign bonds by international investors has risen slightly in two months amid concerns about eroded public finance options following the collapse of the Finance Bill 2024, which contained a raft of new and higher tax measures.

With little room for President William Ruto’s government to cut spending, yields on Kenya’s medium-term bonds traded on the London Stock Exchange have risen 2.02 percent since the successful youth-led anti-tax demonstrations.

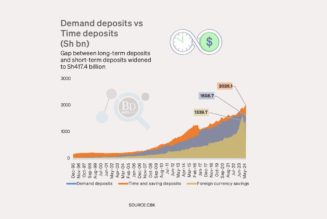

Investors demanded 11.37 percent to buy Kenya’s seven-year Eurobond maturing in 2027 last Thursday, compared with pre-demonstration levels of around 9.35 percent on June 19.

“The concern is that, with public finances set to remain under pressure, reactive measures like increased spending or deficit monetisation will be embraced rather than concrete measures to improve governance and institutional strength,” David Omojomolo, Africa economist for UK-based Capital Economics, said in a note. “Not only will this mean that GDP growth continues to struggle and that the threat of unrest continues to linger over the outlook, but also that concerns about the long-term sustainability of the public finances will mount.”

Unrelenting youth-led demonstrations against International Monetary Fund-backed new tax hikes, the rising cost of living, poor governance and corruption prompted President William Ruto to withdraw Finance Bill 2024, leaving a Sh344.3 billion budget gap.

The country’s weakening fiscal position was further weakened by last month’s downward revision of recurrent revenue collection by Sh280 billion to Sh3.06 trillion. This was to reflect a similar shortfall in actual collections for the year to June.

In preparing the budget, the Treasury and lawmakers had expected actual collections for the last fiscal year, mainly taxes, to be Sh2.92 trillion. But revenues fell short by Sh280 billion.

In the supplementary budget that Dr Ruto pushed through on August 5, lawmakers slashed the total budget by Sh145 billion — comprising Sh105 billion for development projects and Sh40 billion for the operation and administration of public offices and remuneration of staff.

However, the budget cuts were less than the Sh177 billion announced by the president on July 5.

This was after the administration ran out of room to cut spending in key education, health and security sectors. Some of the key budget allocations that were retained include Sh31.3 billion for the Higher Education Loans Board, Sh18.7 billion for Junior Secondary School interns’ confirmation, University Funding Board scholarships (Sh17 billion), the posting of medical interns (Sh3.7 billion) and salary increases for internal security officers (Sh3.5 billion).

The decision to scrap Sh10 billion for teachers’ salary increases, which was to take effect in July, has prompted union leaders to threaten industrial action. This is likely to disrupt learning in primary and secondary schools when they reopen on August 26.

Mounting pressure on Kenya’s public finances has led two major global credit rating agencies — Moody’s and Fitch — to downgrade Kenya’s credit rating to junk, raising fears of a sovereign default on medium to long-term debt.

Fitch said the downgrade “reflects heightened risks to Kenya’s public finances after the government backtracked on revenue measures in the 2024 Finance Bill in response to violent social protests, the increased risk to political stability, and rising domestic costs even as the authorities embark on spending cuts”.

Investors have also raised Kenya’s credit risk profile to levels last seen at the end of last year, in response to the decision to backtrack on IMF-backed tax increases and the unresolved threat of disruptive demonstrations.

The yield on Kenya’s 10-year Eurobond maturing in 2028 is hovering around 11.51 percent, up from 9.71 before the protests, while investors are demanding 11.74 percent for the six-year bond (raised from 10.21 percent in mid-February), up from 10.22 percent on June 19.

The yield on the 12-year government bond maturing in 2032 has risen to 11.62 per cent from 10.32 per cent over the period, while the rate on the 13-year Eurobond maturing in 2034 is 11.54 per cent from 10.28 per cent before the demos.

Kenya’s fiscal consolidation framework relies heavily on tax increases, unlike countries such as Nigeria, which has room to cut fuel subsidies. The revenue shortfall after the new tax measures were scrapped this fiscal year is likely to be bridged by increased borrowing.

“It looks increasingly likely that the government will struggle to place public debt on a downward trajectory. The chances of a sovereign default in the coming years are rising again, and would jump if the IMF were to pull its support,” Mr Omojomolo wrote.

“Debt servicing costs are now equivalent to close to 30 percent of government revenues. Meanwhile, the public appears to have grown increasingly distrustful of the government, especially as projects have been beset by delays or not materialised, all amid corruption allegations.”