In May 2018, Kenya ratified the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement, becoming one of the first countries on the continent to adopt the pact meant to remove trade barriers and encourage investments.

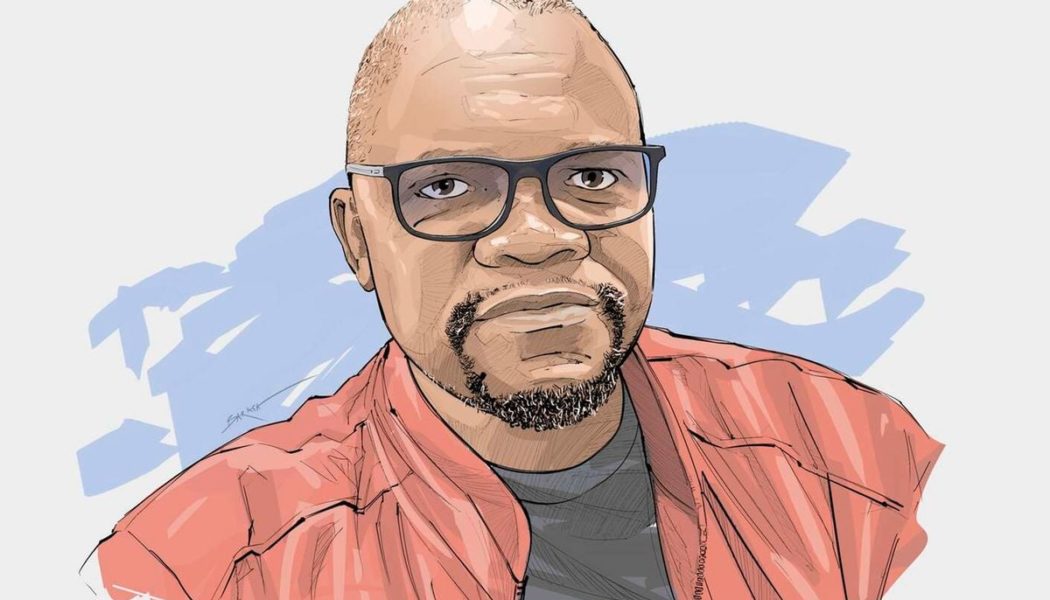

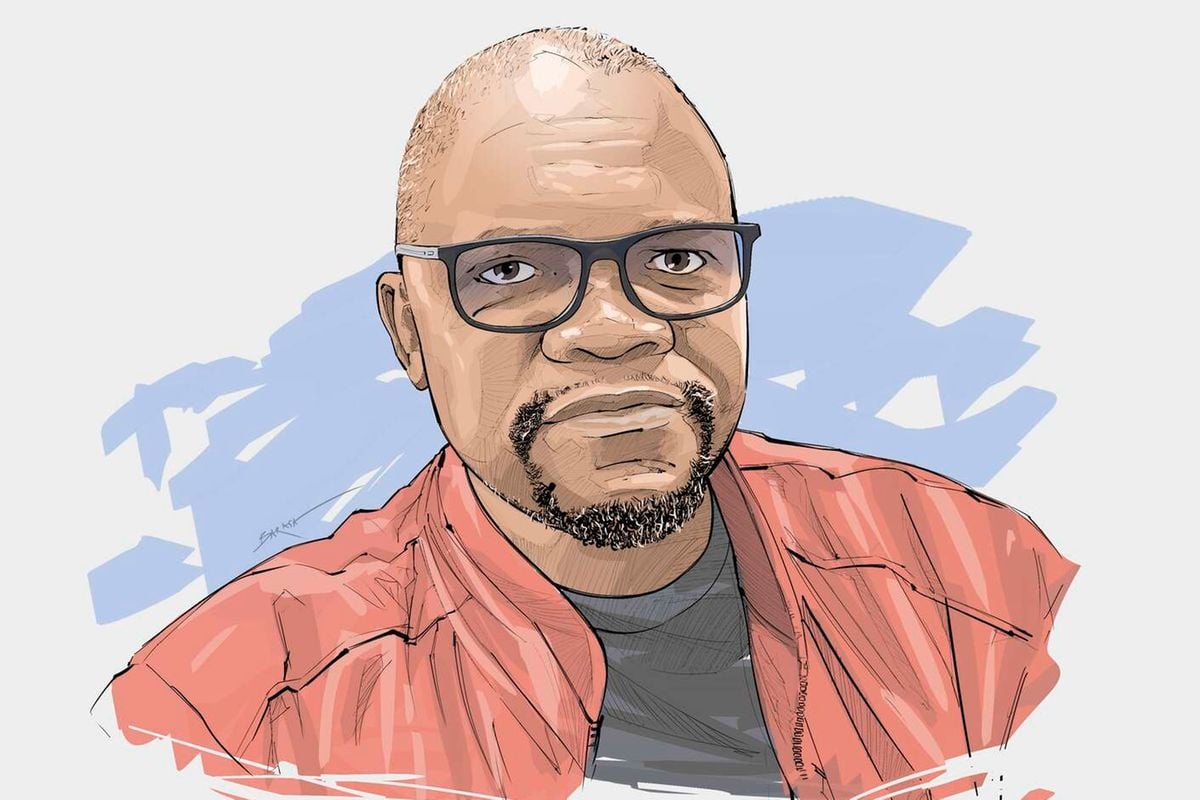

With the free flow of trade and investments, there will inevitably be labour movement as companies seek specialist skills to support their cross-border investments. The Business Daily sat with Willys Mac’Olale, the immigration director at global immigration services provider Fragomen Kenya Ltd, to discuss the potential impact of the trade pact on labour movement trends in Africa once it is fully adopted.

How do you see AfCFTA affecting the inward movement of labour into Kenya?

AfCFTA removes trade barriers and encourages investment, and companies move with experts that they already know or that they want to engage to get their business running.

So when countries open up for investment and trade, then investors also move people in, so that’s how they tie in terms of just getting investments to work and then getting talent to move across borders.

That said, a majority of the workforce will remain local. There is, therefore, a positive effect in terms of talent and skills transfer, because people who come in will likely stay for two or three years to set up the business, but eventually Kenyans get into the roles. This means that we are getting more in terms of value compared to the numbers that are coming as expatriates.

You will find that in a multinational with 500 employees, hardly one or two percent are expatriates.

In Africa, you find some countries have a deficit of skilled labour. Do you see opportunities for Kenyans to go out to other countries in Africa, similar to the way we are exporting labour to Europe and the Middle East?

There is an opportunity. Countries need to look at their areas of strength, whether agriculture, manufacturing, ICT, or innovation and maximise those areas. If that is encouraged in that way, then there’ll be opportunities for skilled labour to migrate as the sectors are developed. There will, therefore, be opportunities for Kenyans to go out there into Africa to do business work and even to invest.

In terms of sectors, agriculture comes first because that’s a rapidly growing area with endless opportunities. Then there is manufacturing, communication and ICT, an area of strength for Kenya that we can tap into.

How would you rate the capacity of the Kenyan economy to take in labour from outside?

We have the capacity and are growing at a rate that allows us to take in external labour, which would not be in big numbers.

Most multinationals, even the big Fortune 500 American companies would have about one or two percent expatriates in any country they are in, largely due to the laws put into place. So we still can take in skilled labour—unskilled labour comes in on its own—but we have more capacity for outward labour flow and that’s why the government is keen on securing opportunities outside there.

What of the potential social impact of labour migration, given that many countries have a deficit in terms of jobs, housing, healthcare, jobs etc?

If you look at labour migration into Kenya, the skilled bit is just a small part. The larger space is occupied by unskilled labour with a significant influx from the neighbouring countries.

There will inevitably be pressure on housing, social amenities, health care, and how the government manages that is critical in terms of ensuring that there is harmony between the local and expat population in a country, whether they are refugees, working in the informal sector, or even in the skilled labour space.

Are there any safeguards within the AfCFTA for labour and job migration?

If you look at the immigration policy and practice in Kenya, there is something called Kenyanisation which requires that certain jobs must be done by Kenyans. It doesn’t matter who the investor is, there are jobs that you cannot bring expatriates to do.

But then besides that, for those that are allowable for expatriates, there is what is called the understudy programme where for every expatriate that you bring, there must be a Kenyan, equally qualified or experienced, to work with a foreigner.

The thinking is that when this foreigner leaves at the end of their tenure, a Kenyan is supposed to take over that job. Or even if this Kenyan doesn’t take over the job directly, they’re supposed to apply their skills elsewhere. Or they’re supposed to work for this multinational in another country.

So, in the skilled labour space, it works well within the immigration law and practice in Kenya. The unskilled labour is not well managed across Africa and will continue to be difficult to manage.

Now that Kenya has adopted a visa free regime, should we be looking to strengthen enforcement around work permits?

From a legal standpoint, it is only good that the work permit regime continues to be in place, especially for skilled labour, because remember, we are talking about a country that is largely affected by high unemployment levels.

The work permit regime is actually meant to make sure that people who come in are those we actually require. The work permit regime system has a way of identifying those skills, and you can’t let it go just like that, otherwise you will have everybody coming into the country and before you know it there is pushback from the citizens.

Are there any local laws that need changing to align ourselves or to take full advantage of the trade pact?

We don’t necessarily need to change, but rather we need to update some to respond to the specific needs of the intra-African business space. For example, tax and immigration laws to allow easier movement of business. We need to look at our policies at that level and see if they encourage investment and trade in goods and services.

If that’s working, we see how to promote them and tell investors how we can support them set up and what they can do in terms of partnerships with government and the private sector.

For instance, the East African Common Market protocol is actually a very good document. But just on paper. When it comes to practice, it is quite different and needs work to make it more effective.