This article originally appeared in ‘Hypebeast Magazine Issue 33: The Systems Issue.’

You’re in the audience at the Sundance Film Festival in 2017. On the screen in front of you, the bulging puffy eyes of a swollen, anthropomorphized neck boil gaze at the camera with an urgent, demented longing. The creature’s odd, circular body twitches uncomfortably as it pleads with its host and her brother-slash-lover to be included in their incestuous, post-apocalyptic sexual escapades. Relenting, the couple agree to the ménage and soon a swollen, vein-covered phallus puppet enters the scene, penetrates the boil’s oral cavity, and proceeds to engage in a session of urgent irrumatio unlike anything you’ve ever seen. At that moment, it’s up to you: leave the cinema in disgust like many of your fellow filmgoers, or celebrate the brilliance of Kuso — the directorial debut of Steve Ellison, aka Flying Lotus — as one of the greatest works of body horror in cinematic history.

Of course, Ellison’s visionary approach to film evokes other fearlessly provocative auteurs like Cronenberg, Tsukamoto, Pasolini, and even John Waters. And given the company on this list, it’s no wonder his debut was met with headlines describing audience walk-outs at its premiere screening. But ask any of the aforementioned directors for their take on such a reception, and they would confidently tell you that this outcome has only one true and proper response: mission accomplished.

Ellison was born in Los Angeles in 1983 and he’s no stranger to pushing the boundaries of what is perceived as possible (or palatable) in art-making. He’s well into the second decade of his music career and is one of the most highly-regarded electronic producers alive today.

As Flying Lotus, he’s not only expanded the perceptions of certain music genres, blending jazz, hip-hop, and experimental influences together with a singular, inspired vision. He’s also taken a visual approach to music and a musical approach to visuals, making him a peerless creative force. It doesn’t hurt, either, that he’s the grandnephew of jazz great Alice Coltrane, has collaborated with everyone from Kendrick Lamar and Thom Yorke to Herbie Hancock, and runs a label, Brainfeeder, that has been a platform for some of the most interesting and important music of the last 15 years.

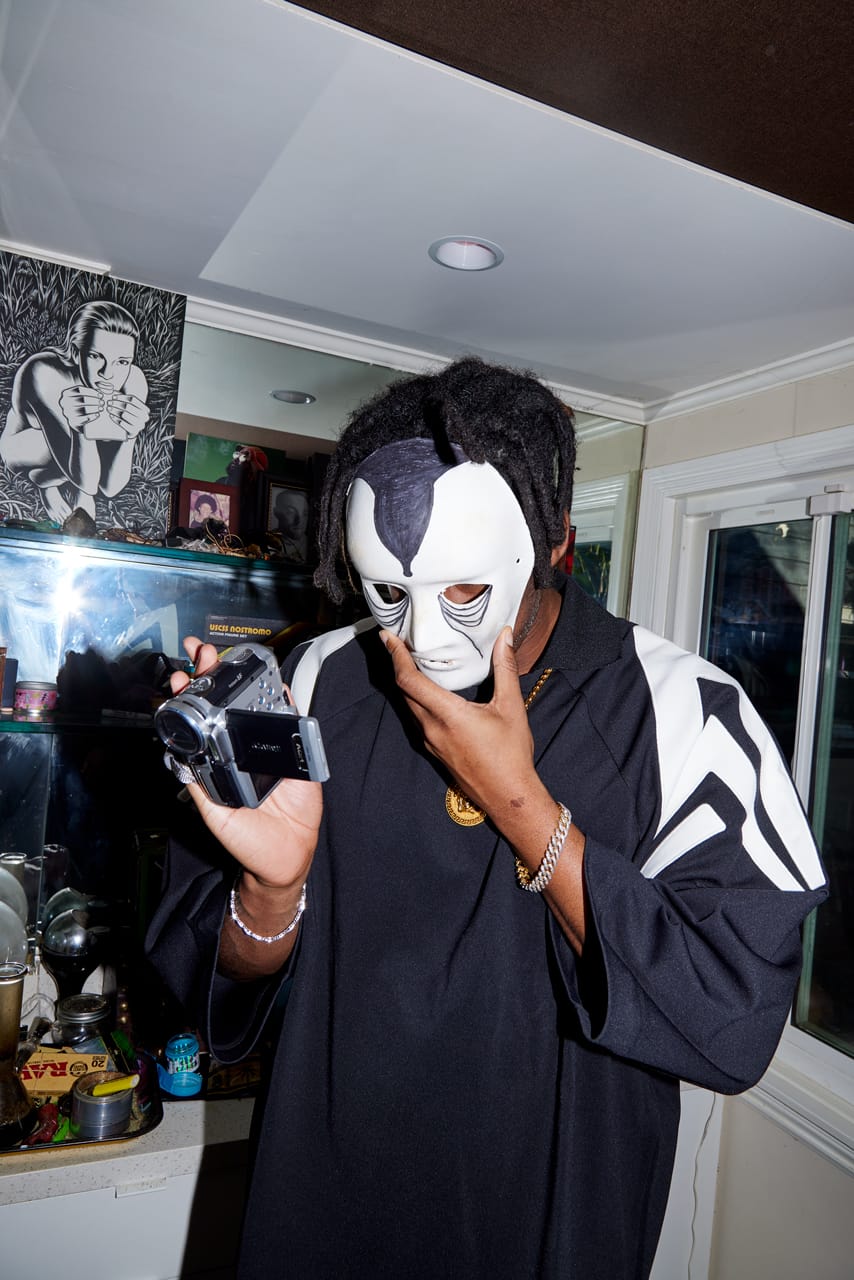

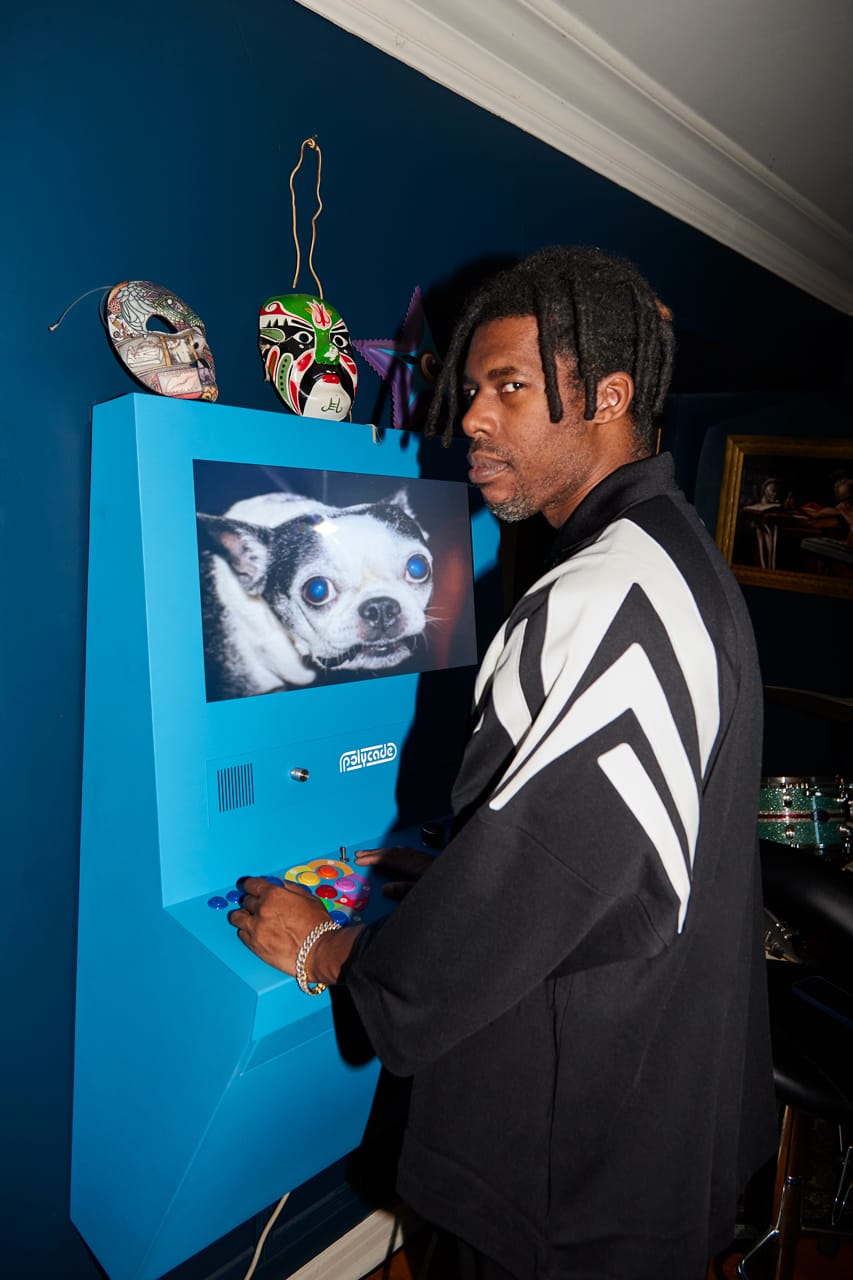

Connecting with Ellison at his home in LA, I find him sitting in his studio control room surrounded by eye-catching artwork, memorabilia, and other ephemera — a glimpse into his broad artistic lens as both a musician and filmmaker. A huge computer monitor in front of his producer desk reveals open playlists he’s been listening to for inspiration (MF DOOM is next in the queue). Perched calmly in the middle of this creative command center, the multi-hyphenate artist takes a moment to play with his dog iko before nodding in my direction, letting me know that he’s ready for our conversation to begin.

“There’s no part of the process that’s been easy, but there are rewards around every corner.”

You’ve got both music and film projects on the horizon that I think people are going to be really excited about. Can you tell us a little bit about what you’ve been working on?

I’ve been working on a new album, as well as a film called Ash. The album is in a state where it’s 98% done. I just need a good solid week of really focusing on that last little bit to get it over the hill, but I’ve just been so deep in this movie thing. It takes a lot of your focus. There’s no part of the process that’s been easy, but there are rewards around every corner.

What have been some of the rewards and challenges of the filmmaking process for you?

The movie’s a sci-fi thriller horror movie. It’s very psychedelic at times. It stars Eiza Gonzalez and Aaron Paul. I didn’t really expect it to take three years of my life. When it was presented to me, it was like, “This movie is ready to go, it’s all good, we can get it going, we can get the cast,” but it took a long time to get it done. We shot it in New Zealand earlier this year. It’s been quite the undertaking.

Was there anyone you could look to as a mentor in the more challenging moments?

One person who was really unexpected was Taika Waititi. He is a friend of Beulah Koale, who’s in the film. I had had a particularly rough day of shooting and for whatever reason, Taika had time and wanted to get dinner. It was the best thing that could have happened to the production. He just sat with me and was like my therapist, like, “Yeah bro, I deal with these challenges, too.” Even though he’s shooting Star Wars, he deals with the same stuff that I deal with. It was really encouraging.

How would you contrast the experience of making Ash with making your previous film, Kuso?

It’s completely different. With Kuso, I did so much of that at my house and a lot of it was me begging homies to do stuff, whereas Ash was a real production. Everything was really legit. Going to an office, being in meetings every day with fluorescent lights. It was great working with professionals who have crazy experience in the industry. People go to New Zealand to shoot sci-fi and fantasy movies, so I was among all these people who worked on The Lord of the Rings and other Peter Jackson and James Cameron stuff.

There was a lot of press around Kuso being hard to watch for some audiences. Do you think viewers will find Ash similarly challenging?

I think it will be challenging for some people, but not in the same way. This is very much a straightforward narrative film. There are some crazy things in it, but I think it’s not as crazy as anything in Kuso. This one is a bit more contained.

“[Music is] more of a stream of consciousness thing. It’s the God zone… or has the potential to be.”

How does your experience with making music bring perspective to what it means for you to be a director?

I’m so grateful to be able to do music. Even if I’m not working on an album, I make music for fun. I don’t need anyone’s approval. But film is such a different thing; you kind of need people around you to know for sure that you’ve explored every possibility. With music, I just tend to think that it’s more of a stream of consciousness thing. It’s the God zone… or has the potential to be.

Talking about music versus film, there’s obviously the classic “play the track in the car” test for music. Do you think there’s a film equivalent?

Oddly enough, I get enjoyment out of seeing things on my phone. That’s going to be most people’s first impression of it anyways, and it’s also my gauge if the color is right. If it looks good on the phone, it’s probably going to look OK for most people. It’s so strange.

When you’re working nonstop on all these things, trying to get them across the finish line, what does a day in the life of Steve look like? Are you super regimented?

I’m just sitting in this f*cking chair doing whatever I can [laughs]. I don’t schedule it like that, but I am focused. I get my stuff done. When it’s your own project, it’s easy to get lost. If it was someone else’s project, I probably wouldn’t be able to go there. But yeah, I’m completely, fully committed to my stuff always. I like to wake up early and drink my coffee and go to the gym and then get to work.

Being in the bubble of your own work can be amazing, but on the other side of that coin, eventually these things get released to the world. As an artist, what’s your perception on the state of media in general right now?

I’ve been thinking about it a lot lately. What really bothers me is how bad the Internet’s gotten. Everybody’s hip to the monetization of their opinions, and everything is about engagement and clicks and likes — even if it’s contrary. You can pay someone to diss you so you can have a reason to clap back at them. There’s nothing genuine anymore. It’s silly, but I do really miss the Wild West of it.

“Honestly, it’s gotten to the point where I only want to listen to records once there’s no one talking about them anymore.”

How do you feel that affects people’s relationship to music?

To me, there are these things that are really important to give an honest ear to. I want to be unbiased and go in and feel how I feel about it and not be taken by the echo chamber. André 3000’s New Blue Sun is an interesting one to look at. The week leading up to that album, everyone was speculating on what was going to happen. There were all these people saying, “What? Should we sample it?” And it was like, “Yo, how about just listen to it first?” Honestly, it’s gotten to the point where I only want to listen to records once there’s no one talking about them anymore.

On past albums you’ve said “This is going to be a guitar record or a Rhodes piano record or a Yamaha CS-60 synth record. For your next record, have you defined what instrument is going to guide it sonically?

Probably strings. It’s just the type of record that it is. It’s more of an ambient album. There’s only a couple beats on it. It’s meant to be thought of as something you put on to fall asleep to, to dream to, or write something to. There’s a lot more from [multi-instrumentalist] Miguel Atwood-Ferguson on this one. I think he’s on every track. It’s really beautiful and he was a super big inspiration. Generally, I’m trying to do something a bit different this time.

Are there any other collaborators? Or moments where you think listeners will be surprised?

There’s some stuff with Ryuichi Sakamoto that we recorded a long time ago and I’m super excited for that to come out. We had sampled his music for a Thundercat album and we just stayed in touch. The dude came out to LA and was here for four or five days. He would just come to the house and work all day and all night. We made a bunch of stuff and Miguel was here, too.

Did he have a specific creative process that stuck out to you as different than other collaborators?

Yeah, he was the first collaborator who really just went around my place, picked up stuff and just hit it with a stick, and then was like, “Let’s record that.” It was really cool seeing the little things that were interesting to him. I had a ceiling fan in here with a chain on it that made this weird little tapping sound. We were recording some stuff and I was like, “Oh let me turn the fan off.” Once the tapping was gone, it just killed the vibe. We all just looked around and were like, “Oh, we better turn it back on.” We had to have that tapping in the background of what we were doing.

Did you ever look over your shoulder and just bug out like “Woah Ryuichi Sakamoto is right here!”?

Me and Miguel are both huge fans. We were like, “Yo, is this really happening right now?” He just brought this very zen energy with him.

Speaking of zen vibes, putting out ambient albums and André 3000, why do you think chillness is so important to proliferate right now?

People’s tastes are so diverse now. As music fans, there’s a time and place for everything. Also, I think because of the time that we’re in, it feels like there’s more urgency to put on stuff that’s a bit more chill. Sometimes we need something that’s not all crazy. There’s a time for the chaos and there’s a time for the chill. There’s enough time for all of it and I think that’s great.