To try to cover the enormous subject of African music in around 120 pages is bold; to add the large topic of black music in America, and attempt to deal with it in 30 pages, is foolhardy. But to take on that second task when you know as little about it as Dr Kebede is suicidal.

So far as my knowledge can guide me, I find the African coverage not bad. The disproportionate emphasis on Ethiopia may be explained by the fact that it is Dr Kebede’s native country; not, however, excused. His musicological standpoint appears to be fairly purist: little is said about modern urban popular music, and the guitar, which has become enormously popular in the past 25 years in many parts of Africa, is mentioned only once, in connection with Central African pygmies. Nonetheless, though several passages left me dissatisfied or suspicious, I did learn a good deal from the account.

On black music in the US, JJI readers will be on more familiar ground, and they may well be moved to astonishment as they gaze at the author stumbling half-blind across it. By a novel distinction he divides blues into country, racial, city and urban types, evidently unaware that for more than 30 years all blues were conceived as – and called – race music. ‘In many cases,’ he states, ‘country and racial blues are sung in Gullah, the black American dialect of the English language.’ So that’s why Charley Patton is so hard to decipher!

‘The use,’ Dr Kebede asserts, ‘of repetitive singles, duples, triples, and quadruple-line stanzas in songs is a common characteristic of vocal music in sub-Saharan Africa. Consequently, the manner in which blues texts are constructed is an Africanism in black American music’ (my italics). As a folkloric thesis this is indefensible: repetitive short stanzas are common in folksong almost everywhere, and one might just as convincingly argue that the blues stanza is a perversion of the British ballad verse.

A glance at Dr Kebede’s bibliographies and discographies reveals all. On the blues he cites only one of Charters’ books (the dubious Poetry Of The Blues (and none of Oliver’s). The discography, consisting of seven entries, includes (I swear): ‘Ma Rainey. United Hot Clubs of America 83-85. Bessie Smith. Columbia 3172-D.’ The chapter on jazz (less than seven pages) skips from Louis to Coltrane in two paragraphs and ignores Ellington, Basie and all jazz of the thirties and forties, whether black or white.

Books like this are published not for JJI readers but for some black studies market. All the more important, then, that they should be, at the very least, soundly based upon wide and up-to-date reading and a basic understanding of discography in its largest sense. But in ethnomusicological circles, until very recently, to have much acquaintance with discography has been regarded as a pointless eccentricity. In that respect, many non-academic jazz writers and researchers have been more genuinely scholars than their professional rivals, and they will be entitled to have scant respect for Dr Kebede’s contribution to the literature of Afro-American music. Such works, in Housman’s useful phrase, are little better than interruptions to our studies.

***

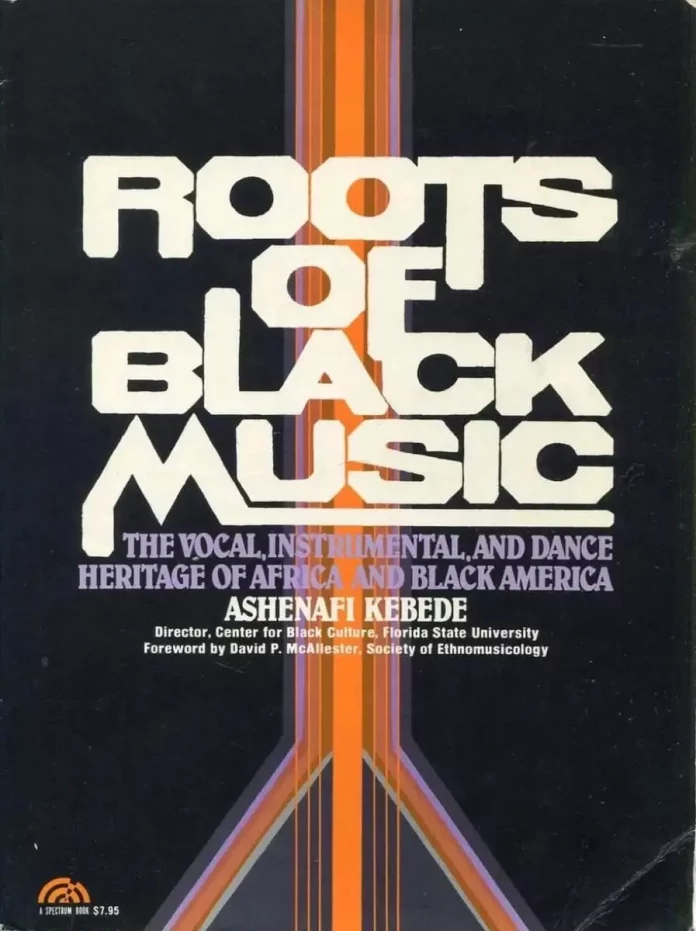

Roots Of Black Music – The Vocal, Instrumental, and Dance Heritage of Africa and Black America. By Ashenafi Kebede. Prentice-Hall, Inc. (Spectrum Books): £6.75 (paper).