Earlier this month, Universal Music Group, the world’s largest record company, ended a boycott of TikTok that began earlier this year over claims that the Chinese-owned social media platform was not paying fair value for the use of its songs and concerns about the use of generative artificial intelligence. According to reports, Universal said the new licensing deal would lead to improved remuneration for its artists and songwriters and included fresh promotional and commercial agreements with protection in the area of AI.

Although other big record label owners were said to be watching the situation with interest, there is a view that Universal’s position — which meant its artists were unable to reach the vast audiences provided by TikTok, which has become a crucial tool for discovering music and promoting it — was undermined by the decision by Taylor Swift to promote her latest album on the platform. Unlike many other artists, Swift owns the copyrights to her songs.

But, also unlike many other artists, Swift is so successful that she almost transcends her industry in such a way that her position is not dissimilar to that of the Big Tech companies. Accordingly, while Universal would obviously like to earn as much as possible in royalties from Swift and other highly popular artists, the dispute is more significant for the smaller players, who have been finding life increasingly challenging.

There has in truth always been an imbalance between individual artists and record labels, publishers, distributors and others, with tales of unfair contracts rife. But what is new is the technology that at once gives artists potential greater reach and brings in less revenue. This is largely because the streaming services pay very little. According to the U.K.’s Musicians’ Union, streaming now accounts for more than 85% of U.K. music consumption. Yet most musicians see little income from Spotify and the various other services. According to Produce Like a Pro, a website designed to help artists starting in the business, it takes between 300,000 and 350,000 streams to generate $1,000 in income. Even then, there is no set formula for how the revenue is distributed.

But it is not just the small amounts of money generated that make life so hard for musicians, producers and labels in specialist areas such as classical and jazz music. Increasingly, the streaming services utilize algorithms to create playlists that increasing numbers of people use to play music as they go about their lives. This is frustrating for artists because they see obtaining a place on such a list as more to do with luck than reward for producing good work. Moreover, the ascendancy of playlists means that listeners often do not know what they are listening to or how they can go about finding more by the same or similar artists. In short, with much more music being made available than ever used to be the case, this is a great time to be a consumer of music but it is not so great for those producing it.

This is only one facet of the entertainment industry as a whole. The challenges facing it were set out in cultural commentator Ted Gioia’s Honest Broker column earlier this year. He argued that the increasingly central role of Big Tech in people’s lives thanks to social media meant that the old idea of culture being a choice between art and entertainment had been usurped because both were being usurped by distraction — the endless scrolling on mobile phones that so many of us spend our spare time doing.

Forward-thinking people in all parts of this world — books, movies, music etc — will have their own ideas for how to counter this seemingly relentless trend. In music, which has an important part to play because it accompanies so much of the content that Gioia regards as distraction and even addictive, one man is seeking to do something to halt the trend. Although he accepts that the situation is serious, Dave Stapleton, a pianist and composer who founded the Edition Records label for jazz and related music 15 years ago, believes that there are opportunities to bring about change. At the heart of his solution are the ideas of a common ground and community. Labels, he said in a recent interview, had to be more than gatekeepers, while artists needed to take control, which required vision and strategy in marketing as well as the music itself.

Some artists — particularly since the pandemic — have already gone down this road, using the likes of Instagram to provide fans with information about themselves that goes beyond their musical tastes and inspirations and even seeking support through such apps as Patreon and Bandcamp. But Stapleton sees a greater role for audiences. Since CDs now play such a minor role in music consumption (with all but the biggest artists only producing between 1,000 and 2,000 units), buying one is not the boost to an artist it might seem. Instead, they should be playing their part in seeking to “humanize” streaming by writing reviews on the platforms and recommending music they like. “It’s about more engagement on streaming,” says Stapleton.

Having had “a lot of conversations” around the topic with people in the industry, he has recently launched an initiative to help turn that talk into action.

Explaining the launch of House of Twelve on LinkedIn earlier this month, he said that releasing music or impacting in any art form was “more complicated than ever, yet I confidently believe there’s plenty of opportunity if you look in the right places.” He added that he wanted House of Twelve to act as a platform for creative people to “connect and share — the challenges, the process and the opportunities.”

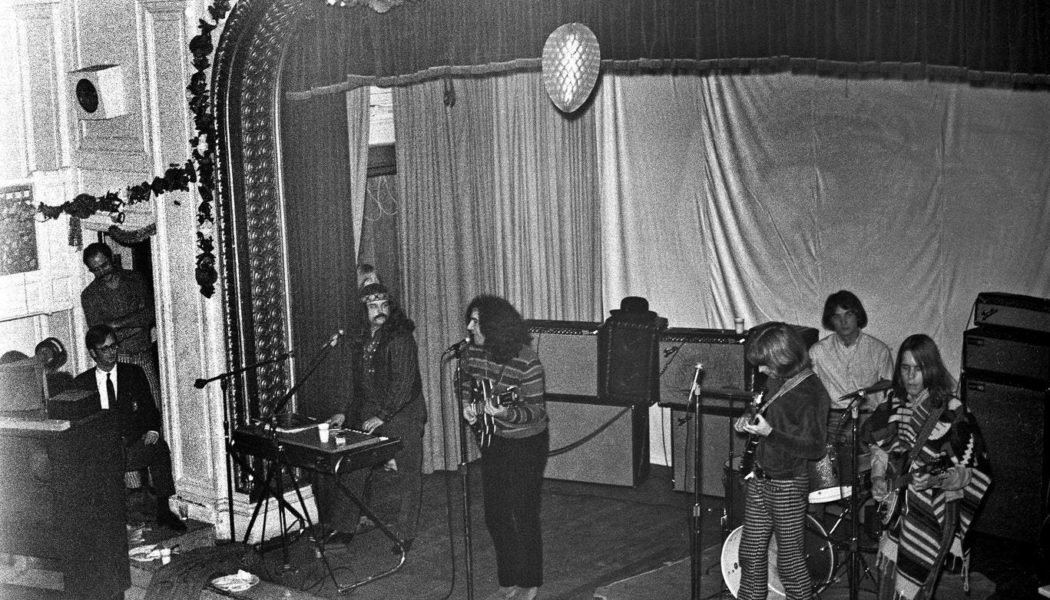

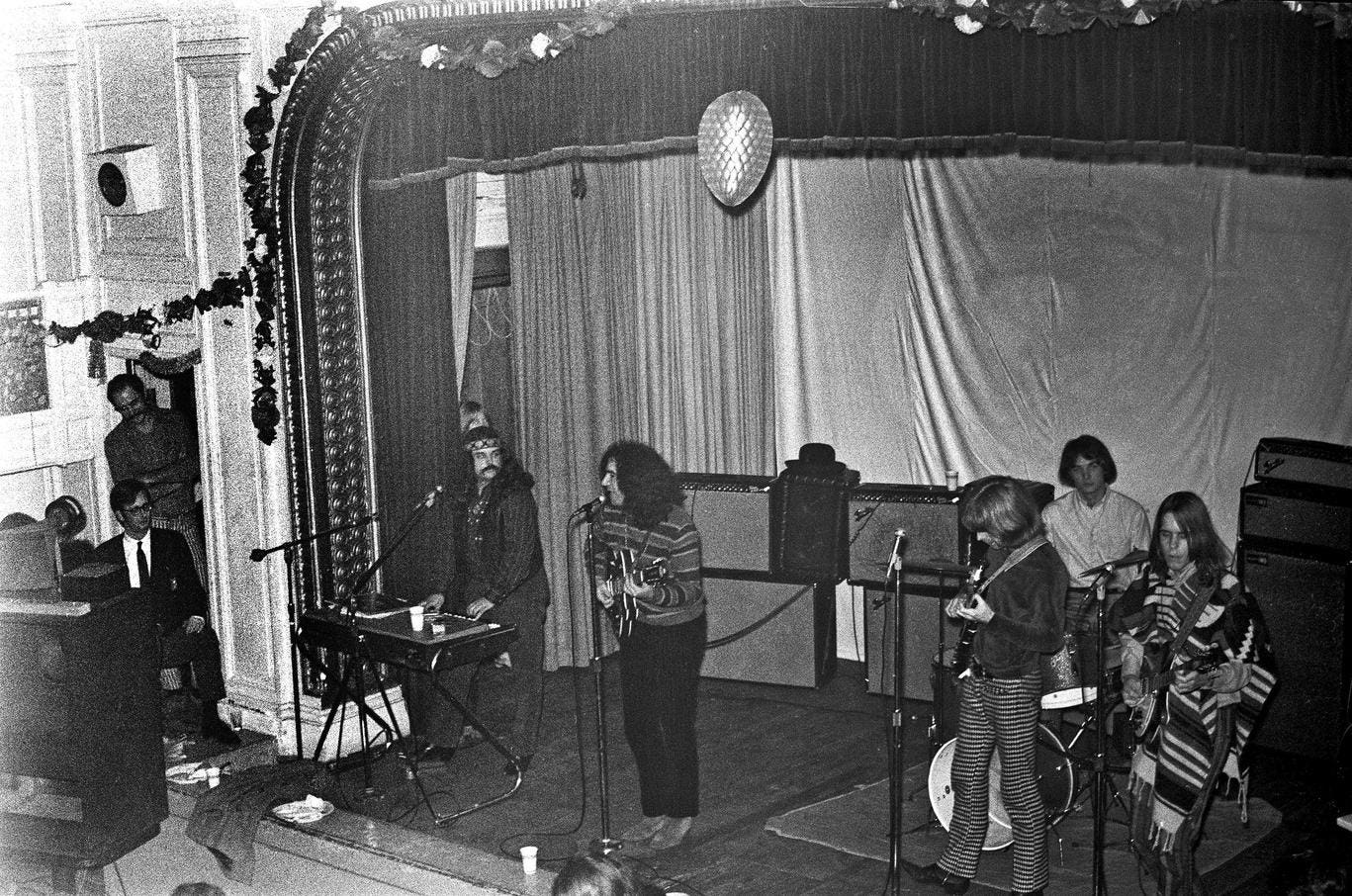

The funny thing is that something like that did happen — in San Francisco in the 1960s, when the “counter-culture” was born. And the musical group perhaps most closely associated with this movement is — unlike many of its contemporaries — still selling music today, largely because it turned its fans into a community early on. As is made clear in Marketing Lessons From The Grateful Dead, one of a number of books looking at this group’s business acumen, the band was a lot more than a bunch of hippies. Rather, it was pioneering in encouraging fans to tape their shows, often making the results available to others later on; selling tickets for their live performances direct to fans rather than through agencies and generally seeing their followers, or Dead Heads, as partners rather than mere consumers.