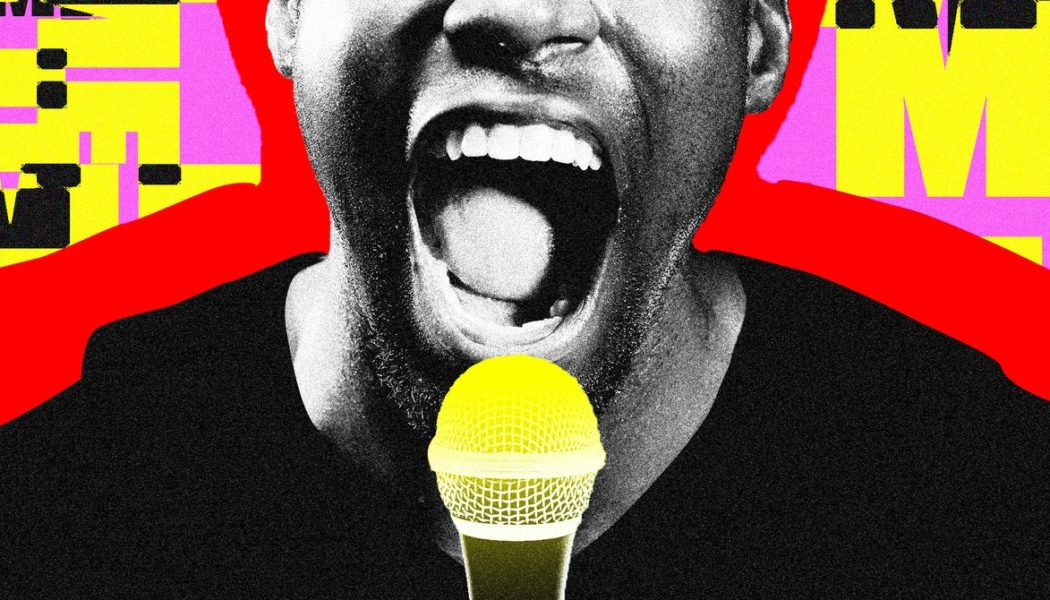

Future and Metro Boomin’s “Like That” landed with the force of an atomic bomb. Released last month, the thumping diss track hit the Billboard Hot 100 in a flash but went dynamite across X, Instagram, and TikTok thanks to a surprise verse from Kendrick Lamar, the Compton rapper who won a Pulitzer Prize in 2018 and who is considered by many to be the best rapper alive today. It reverberated not just because of Lamar’s lyricism but because of who the lyrics were calling out: his friends turned frenemies, Drake and J Cole.

Together, the three of them are considered to be among rap’s current elite, a claim Lamar took issue with. In a flurry of vicious one-liners, he made clear that the throne was his alone. (“Muthaf*** the big three / it’s just big me” is one of the jabs everybody refuses to shut up about.) Lamar is a nimble technician who has a mind-melting sense for narrative, scene, and plot in his song writing, and though reactions varied—Drake and Cole fans are loyal to the end, even when they’re on the losing side—there was no denying Lamar’s lyrical aptitude on “Like That.”

“The way Kendrick slid on ‘Like That’ was diabolical,” @BigKing_103 wrote on X. The song has everything you could want: hypnotic production, orb-flashing synths, lyrics seared into memory, the kind that are furiously debated in comment sections. “Kendrick’s verse on ‘Like That’ only gets harder with every listen,” added @beentrillbeyond.

According to new research, “Like That” is indicative of a recent trend in music—and also something of an outlier. The song underscores Lamar’s canny virtuosity in what is already one of the most memorable verses of the year (the outlier part) but is just as striking for its playfully repetitive hook (the phrase “like that” is repeated more than 30 times). A recent study published in Scientific Reports found that lyrics across the genres of rap, rock, country, R&B, and pop have exhibited a “decline in vocabulary richness.” Conducted by a team of European researchers, the study surveyed 353,320 English-language song lyrics from 1970 to 2020, using the platform Genius and zeroing in on key descriptors—structure, rhyme, emotion, complexity—to gauge songwriting’s “temporal evolution over the last decades, and genre-specific variations.”

The key findings pinpoint a deterioration in lyrical content, citing a “general increase in repetitiveness” across the five major genres. For rap, the study found, “lyrics seem to become more emotional with time” and “less positive for R&B, pop, and country.” One of the major conclusions was that music, overall, is exhibiting “a trend toward angrier lyrics.”

This new study jibes with a 2011 psychology study that looked at music spanning 1980 to 2007, concluding that there was a considerable decline in the words “we” and “us” while “I” and “me” were featured more frequently in song lyrics.

Changing song patterns reflect the spirit of the era they are born into. Society today is more egocentric. Much of the way we live is mediated through digital portals that require a mode of self-centering as part of their hook. Modern songs may be characterized by their anger, monotony, and vanity, but those attributes are not an indictment of the times. Data never accounts for the complete story. The better question is why that may be the case.

Not everyone is buying it. Despite the study’s findings, “I don’t believe hip-hop lyrics are more angry,” says Dame Aubrey, head of A&R for CMG Records and Management, a music label that represents rappers Moneybagg Yo, BlocBoy JB, and GloRilla. If anything, Aubrey says, what changes we do hear are a product of how music has expanded. It’s simple, Aubrey says: more people, more perspectives. The medium is more accessible now because of the technology available. “There’s just a lot more artists with opportunities to be heard because it basically became a trend to make music.”

One major adjustment in all of this is the mechanics of how a song gets popular, and what its popularity generates.

In the age of social media, that can often translate into more of the same kinds of sounds, although that is not always the case. So when Lamar throws punches at Drake—dubbing him one of the “goofies with a check” and following that with “Fore all your dogs gettin’ buried / That’s a K with all these nines, he gon’ see the pet cemetery”—the verses gain traction on X because they feed into the theatrics of online socializing, which is defined by joy and camaraderie between users as much as heated confrontation.

Rap has always gotten, well, a bad rap. Ego, anger, swagger—those emotions are part of the genre’s raucous identity. Since hip-hop’s founding 50 years ago, artists have wielded those sentiments to illustrate their realities. Rap is sport. It’s theater. It is the very kind of music that encourages the style of intense engagement that is increasingly common among fans online.

Are less positive song lyrics actually on the rise, or is the popularity of a certain kind of song simply a reflection of what we think the algorithm wants to hear?

Streaming transformed the music industry in every way possible. Crafting hit songs is somehow easier but just as difficult. The winds of virality can still be unpredictable. Although it is not an exact science, what is evident is how streaming playlists help deliver a song to large audiences in ways analog media couldn’t.

“While there are certainly trends in organic popularity, one unique thing about playlists is the significance and importance of context,” says JJ Italiano, head of global music curation and discovery at Spotify. “Even the most popular songs can vary wildly in how well they perform, depending on the playlist that they’re in and the other songs around them in that playlist.”

Dasha’s recent viral hit “Austin” had around 10,000 streams when Spotify editors began programming it for their playlists, Italiano says, and it did best when paired with similar on-theme pop songs that straddle country and pop, sequenced among summery, guitar-driven tunes (like Noah Kahan), narrative-rich country songs (like Zach Bryan), or similar heartbreak tracks from a different genre (like Mitski). “Eventually the song became so popular on Spotify that it made its way into our most popular playlist, Today’s Top Hits,” he says. But over time, Italiano notes, sequencing does become less crucial to a song’s lifespan as listeners develop a “deep familiarity” with the song.

Artists, then, find themselves making music in line with what’s trending, trying to achieve the same level of reach that songs like “Austin” or “Like That” did. In years past, everything from war to heartbreak influenced the music of the moment. That’s still true, but now TikTok, X, and other platforms drive the conversation as much as anything else. “Social media definitely plays a part in song writing just as the community, movies, and television once played a part,” Aubrey says of rap. Depending on the temperature of exchange among users, which swings from lukewarm to indignant depending on the artist, it prompts certain songs to dominate the conversation. Taylor Swift’s most popular online tracks are often the ones detailing scorn.

Even an artist like Milwaukee rapper Khal!l, who told WIRED in August that he wanted to “create an atmosphere where we can mosh-pit but then also cry and hold hands and shit,” finds himself beholden to the algorithm. He got famous thanks to TikTok, and the best way to sustain his presence on the app is to feed it the content that resonates: “We gotta ride this horse ’til the hooves fall off.”